Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

A few days ago a picture appeared on a number of news websites. It was from a medical examination, an ultrasound image of a mans testicles; there was a face in there as clear as day, with eyes, a nose, and mouth, a child gazing disconcertedly out of its darkness in the depths of the body. The phenomenon is not uncommon and has often been associated with Christ, perhaps because only his face makes such occurrences noteworthy enough to report on. The face of Jesus can appear in a marble cake, a slice of burnt toast, a stained piece of fabric. Last autumn I was stopped by a woman on the street in Gothenburg. She wanted to give me a photograph of Christ seen in a rock face somewhere in Sweden. These viral images are not vague schemata filled in by vivid imaginations, but are utterly convincing; the face staring out of the mans testicles is incontestably that of a child, and the male figure in the rock face, his hand held up in a gesture of peace, is incontestably an image of Jesus Christ exactly as he has been iconized. This is because the forms that occur in the world are constrained in number, and the human face and body are one such form. They can just as easily appear in a pile of sand as in a pile of cells.

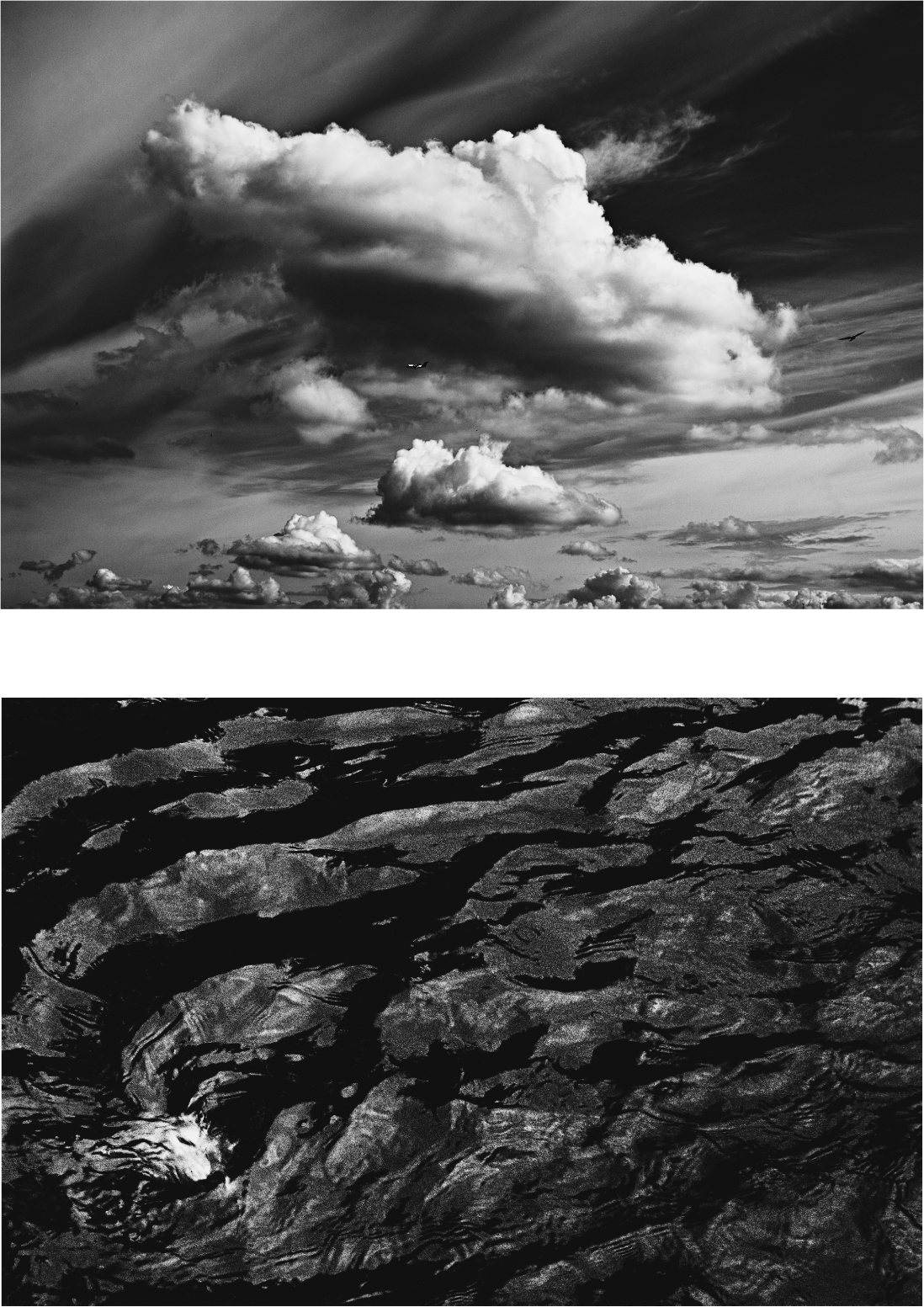

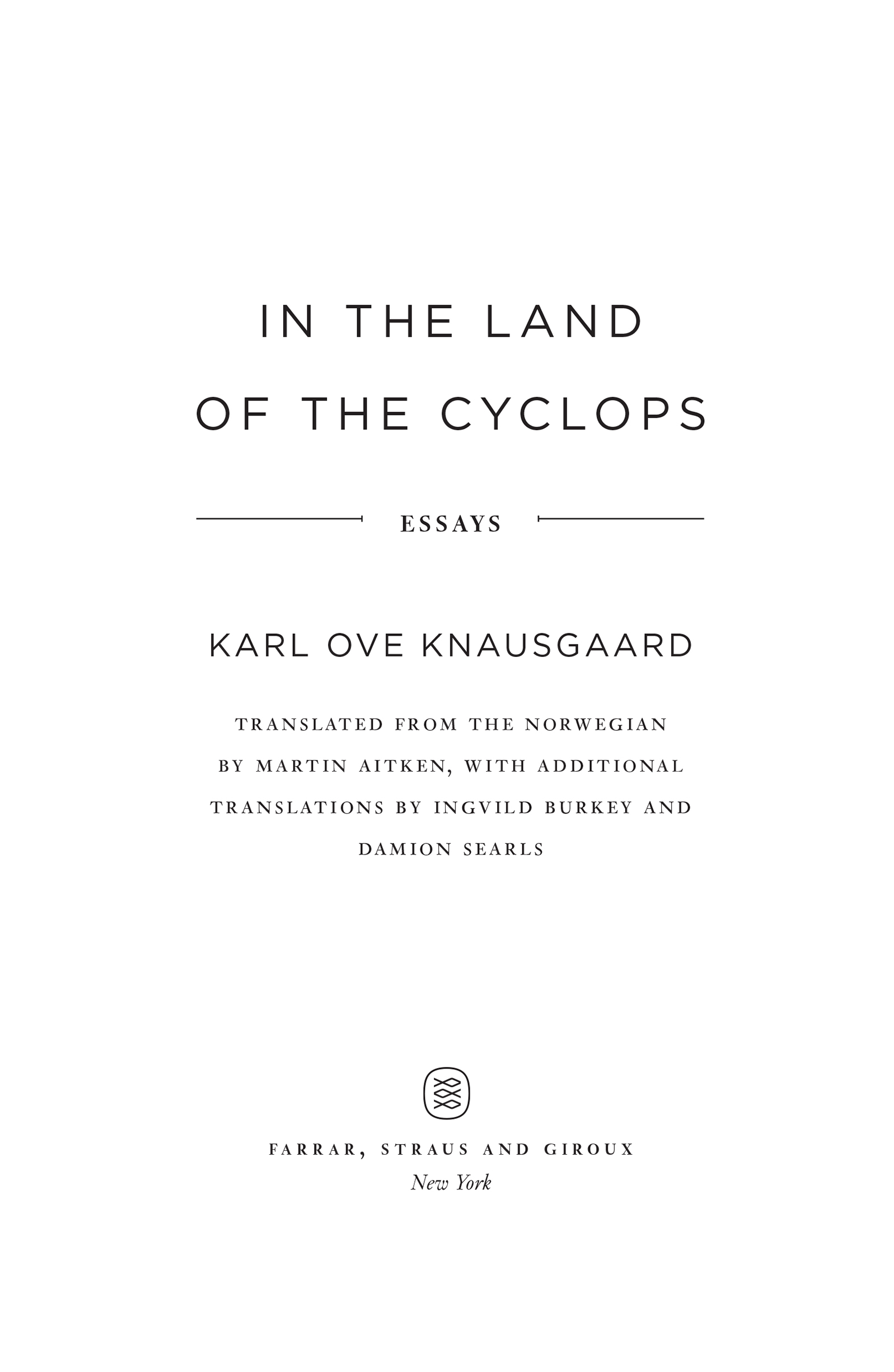

If you lie on your back and look up at the sky on a summers day, hardly a few minutes will pass before you see a recognizable shape in the clouds. A hare, a bathtub, a mountain, a tree, a face. These images are not fixed; slowly they transform into something else, as opposed to the person lying there looking at them, whose face and body remain unchanged, and to the natural surroundings from which they are observed: the ground with its grass and trees, they too remain unchanged. But the immutable is only seemingly so, for the face, the body, the grass, and the trees change too, and if we return to the same spot, this clearing in the forest, fifteen years later, it will be completely different and the face and body will also have changed, although they will still be recognizable. However, in the greater perspective of time they too will transform; over a two-hundred-year period the face and body will have come into being, formed, deformed, and dissolved in sequences of change not unlike those undergone by the clouds, though far more slowly since these changes take place in the denseness of the flesh rather than in the vaporous firmament.

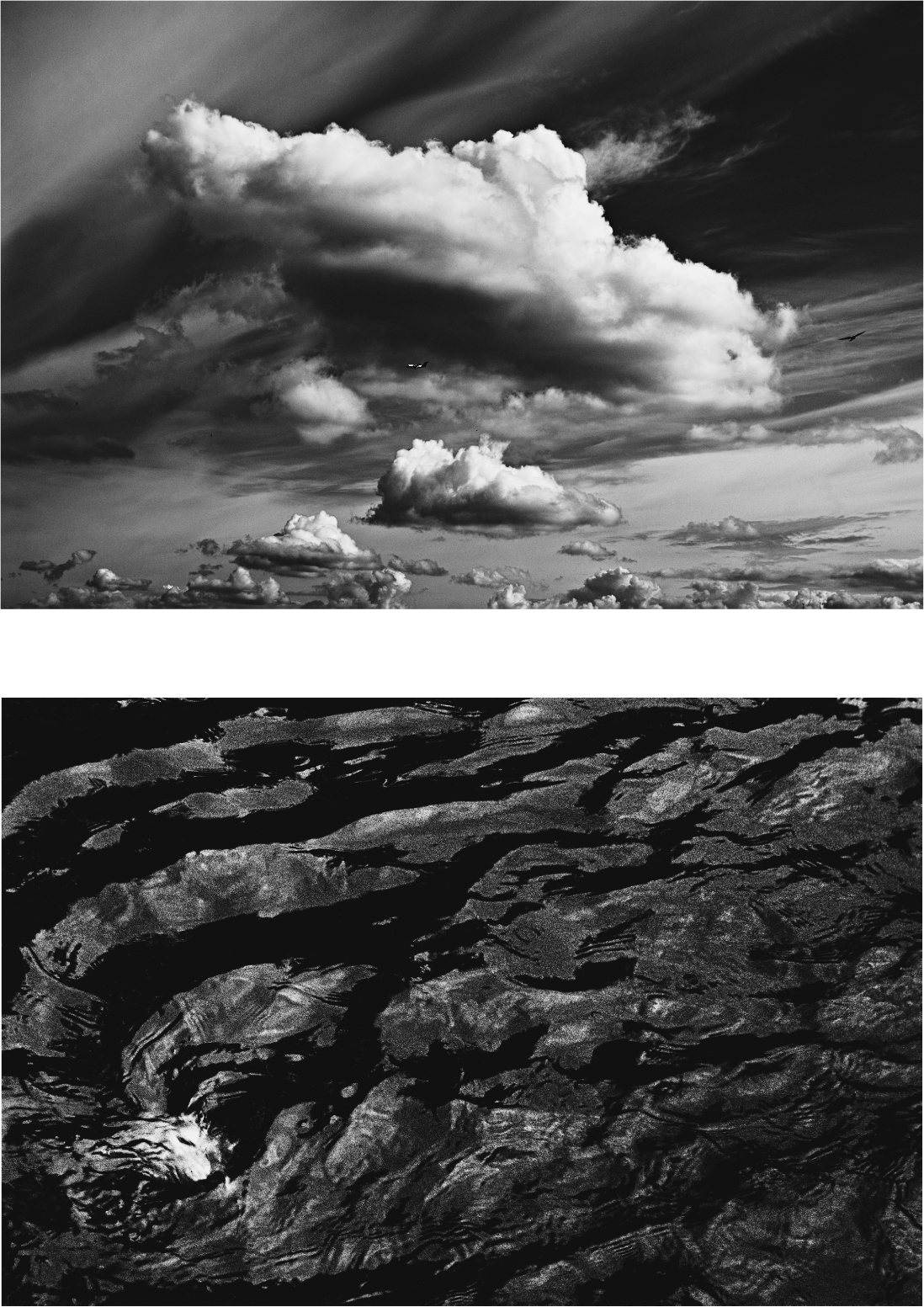

That we do not see the world in this way, as matter at the mercy of all-destructive forces, is only because that perspective is not available to us, our being confined within our own human time as it were, and viewing all change from that vantage point only. We see the changes in the clouds, but not the changes in the mountains. On this basis we form our conceptions of the immutable and immutability, of change and changeability. We retain in our minds the form of the mountain as it appeared to us the day we stood in front of it, but not the forms of the clouds that were above the mountain at that same moment. Our body exists somewhere between these monitors of mutability that measure the speed of our lives. Our own time, the change we are able to register as we stand here in the midst of the world, is, apart from the movements of the body, almost always bound up with water and wind. The raindrops that drip from the gutter, the leaf whirled into the air, the clouds that slip over the ridge, the water that trickles toward the stream, the river that runs into the sea, the waves that form and break apart in an ever-changing abundance of unique forms. We can see this, for the time in which such movement occurs is synchronized with that of our own existence. We refer to that time as the now. And what happens within us in the now is not dissimilar to what happens outside us, a continual formation and breaking apart that never ceases as long as we live: our thoughts. On the sky of the self they come drifting, each unique, and over the precipice of oblivion they vanish again, never to return in the same shape.

The idea of a connection between our thoughts and the clouds, between the soul and the sky, is ancient and has always been opposed, or restrained, by the connection between the body and the earth. That which is fleeting, ethereal, and free has always been eternal; that which is firm, material, and bound has always been transient. With the arrival of modern science in the seventeenth century, which overcame the limitations of the human eye with the invention of the microscope and the telescopean era in the Western world where the human body began to be systematically dissectedone of the greatest challenges to arise concerned the nature of thought in this system of cells and nerves. Where was the soul in this mannequin of muscles and tendons? The French philosopher Descartes performed dissections in his apartment in Amsterdam, striving to find the seat of the soul, which he believed to be located in one of the glands, and trace human thought, which he believed to be conducted through the tiny tubes of the brain. Science has come no closer to pinning down these concepts in the three hundred or so years that have passed since Descartes made his investigations, for the distinction between the I who says I think, therefore I am, and the brain in which that sentence is conceived and thought, and from which it then issues, that biological-mechanical welter of cells, chemistry, and electricity, is immeasurable, as one of Descartess contemporaries only a few city blocks away, the painter Rembrandt, demonstrates in one of his dissection pictures, where the upper part of the skull has been removed and held out like a cup by an assistant while the physician himself cautiously cuts into the exposed brain of the corpse. No thought, only the tubes of thought; no soul, only its empty casing. What were thought and the soul? They were what stirred inside.

In his essay collection Descartes Devil: Three Meditations, a substantial and near-fuming apologia for Descartes, the German poet Durs Grnbein writes about one of the Baroque philosophers dissections of an ox in whose eye Descartes claimed to have seen an image of what the ox itself had seen in its final seconds of life. Descartes writes: We have seen this picture in the eye of a dead animal, and surely it appears on the inner skin of the eye of a living man in just the same way. Of this strange idea, Grnbein writes: Descartes, who imagines the retina as a sheet of paper, as thin and transluscent as an eggshell, really believes that something seen is somehow imprinted on it.

We do not see the world, we see the light it throws back at us, and the thought that this light in some way affixes itself to the inner eye is perhaps not as far-fetched as it seems, for when we close our eyes and block out the light of the world, we have no difficulty conjuring up an image of it from the darkness inside our skulls. That it does not happen in the way Descartes imaginedan image of the seen attaching to the retinal membranedoes not alter the fact that the world exists inside us in the form of pictures, for of all the light that is continually thrown back at us from objects and phenomena, some will always make an impression on us and remain, and that these impressions should have an objective existence, discernible not only by the inner I but by other people too, for instance during a dissection of the eye, is no odder an idea than that the soul should exist independently of the body through which it expresses itself.