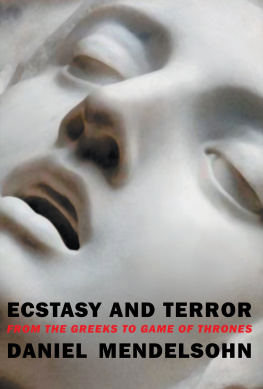

Ecstasy and Terror

From the Greeks to Game of Thrones

DANIEL MENDELSOHN

New York Review Books New York

New York Review Books New York

This is a New York Review Book

published by The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2019 by Daniel Mendelsohn

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (detail), 16471652 (Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome)

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mendelsohn, Daniel Adam, 1960 author. | Levin, Anna, 1961

Title: Ecstasy and terror : from the Greeks to Game of Thrones / by Daniel Mendelsohn.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2019] Identifiers:

LCCN 2019012373 (print) | LCCN 2019981315 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681374055 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681374093 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Literature, ModernClassical influences. | Civilization, WesternClassical influences. | Classical literatureInfluence. | Civilization, ClassicalInfluence. | Civilization, Ancient, in popular culture. | Mendelsohn, Daniel. | CriticsUnited StatesBiography. | Film criticsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN883 M46 2019 (print) | LCC PN883 (ebook) | DDC 801/.95dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019012373

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019981315

ISBN 978-1-68137-409-3

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

For Lily Knezevich

Contents

Preface

I N THE AUTUMN OF 1990, when I was thirty years old and halfway through my doctoral thesis on Greek tragedy, I started submitting book and film reviews to various magazines and newspapers; a few of these were accepted, and within a year Id decided to leave academia and try my hand at being a full-time writer.

On hearing of my plans, my father, a taciturn mathematician who I knew had abandoned his own PhD thesis many years earlier, urged me with uncommon heat to finish my degree. Just in case the writing thing doesnt work out! he grumbled. Mostly to placate him and my motherId already stretched my parents patience, to say nothing of their resources, by studying Greek as an undergraduate and then pursuing the graduate degreeI agreed to stay the course. I finished my thesis (about the role of women in two obscure and rather lumpy plays by Euripides) in 1994 and took the degree. A week after the graduation ceremony I moved to a one-room apartment in New York City and started freelancing full-time.

This bit of autobiography should help explain both the style and content of much of my writing over the past three decades. Back in the mid-1990s, when I was first settling into my writing life, I was eager to write about genres and subjects (movies, theater, music videos, opera, television; family history, parenthood, sexuality) that I would never have been able to delve into as an academic classicist. This I began to do. But early on in my freelancing career I was often asked by editors who were aware that Id done a degree in classics to review, say, a new translation of the Iliad, or a big-budget TV adaptation of the Odyssey, or a modern-dress production of Medea. I ended up finding real pleasure in these assignments, largely because they allowed me to write about the classics in a way that was, finally, congenial to me. My graduate school years had coincided with a period in academic scholarship remembered today for its risibly dense jargon and rebarbative theoretical posturing. In writing for the mainstream press about the ancient cultures that Id studied, I could think and talk about the Greeks and Romans in a way that for me was more natural, more conversationalputting my training in the service of getting readers to love and appreciate the works that I myself loved and appreciated. And yet, when writing about movies, or TV series, or current fiction, I often found myself invoking the classics as models for thinking about contemporary culture. That cross-pollination between the classics and popular culture has characterized most of my writing.

The desire to present the ancient Greeks and Romans and their culture in a way that meaningfully connects the past to the present informs many of the pieces in the first part of this collection. One examines the furor over the burial of Tamerlan Tsarnaev, one of the Boston Marathon bombers, in the light of Sophocless Antigonestill the most relevant of Western texts about certain pressing moral questions, not least the dignity in death to which even our enemies are entitled. In another, the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy allows me to ponder the enduring fascination of that culturally traumatic historical event, which, I argue, lingers in the national consciousness precisely because it so uncannily replays important elements from myth. A recent essay occasioned by a new translation of the Aeneid finds that Virgils epic turns out to have surprising contemporary resonance, anticipating as it does the great historical horrors of the twentieth century: mass extermination, refugee crises, the fragmentation of personality that results from trauma.

And yet the mirror of the past is sometimes a distorting one: the likeness that we often want to see between ourselves and the Greeks and Romans can be deceptive. In some of these Ancient essays, I focus on the ways in which our interpretations and adaptations of the classical can ultimately say more about us than they do about the ancients. As I argue in a review of a recent book about the Parthenon, our eagerness to see that famous ruin as the iconic classical building prevents us from appreciating how avant-garde it was when it was built; a new translation of Sappho provides an occasion to think about why that poet with her intense, eroticized subjectivity has meant so much to us todayalthough what she means to us turns out to be quite different from what she may have meant to the Greeks. This section of the collection ends with my essay on the modern Greek poet Constantine Cavafy. A twentieth-century writer who repeatedly turned to Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, and Byzantine Greek history and literature for his inspiration, Cavafy created a body of work that pays homage to the ancient Hellenic history while discouraging any facile parallels with the present: a model of how to simultaneously reanimate and refashion the past through writing.

Most of the twenty essays collected here are not about the classics per sealthough inevitably, and I hope interestingly, some of them betray the influence of my classical background. (Hence a review of a pair of recent movies about artificial intelligence, Ex Machina and Her, beginsnecessarily, as I see itwith a consideration of the robots that appear in Homers Iliad and what they imply about how we think about the relationship between automation and humanity.) Just over half of the critical essays here survey writers and writing of the recent past, along with films and television: from Evelyn Waugh to John Williams (whose Augustus, a fictional evocation of the Roman emperor, is his finest treatment of themes that go back to his posthumously best-selling Stoner) to Henry Roth and the philhellenic British travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor. Here once again, what often interests me is not only the book I happen to be reviewing but what our reaction to the work or its author says about us: how the fervent critical embrace of Hanya Yanagiharas

New York Review Books New York

New York Review Books New York