S OME TIME AGO, when I was six or seven or eight years old, it would occasionally happen that Id walk into a room and certain people would begin to cry. The rooms in which this happened were located, more often than not, in Miami Beach, Florida, and the people on whom I had this strange effect were, like nearly everyone in Miami Beach in the mid-nineteen-sixties, old. Like nearly everyone else in Miami Beach at that time (or so it seemed to me then), these old people were JewsJews of the sort who were likely to lapse, when sharing prized bits of gossip or coming to the long-delayed endings of stories or to the punch lines of jokes, into Yiddish; which of course had the effect of rendering the climaxes, the points, of these stories and jokes incomprehensible to those of us who were young.

Like many elderly residents of Miami Beach in those days, these people lived in apartments or small houses that seemed, to those who didnt live in them, slightly stale; and which were on the whole quiet, except on those evenings when the sound of the Red Skelton or Milton Berle or Lawrence Welk shows blared from the black-and-white television sets. At certain intervals, however, their stale, quiet apartments would grow noisy with the voices of young children who had flown down for a few weeks in the winter or spring from Long Island or the New Jersey suburbs to see these old Jews, and who would be presented to them, squirming with awkwardness and embarrassment, and forced to kiss their papery, cool cheeks.

Kissing the cheeks of old Jewish relatives! We writhed, we groaned, we wanted to race down to the kidney-shaped heated swimming pool in back of the apartment complex, but first we had to kiss all those cheeks; which, on the men, smelled like basements and hair tonic and Tiparillos, and were scratchy with whiskers so white youd often mistake them for lint (as my younger brother once did, who attempted to pluck off the offending fluff only to be smacked, ungently, on the side of the head); and, on the old women, gave off the vague aroma of face powder and cooking oil, and were as soft as the emergency tissues crammed into the bottom of their purses, crushed there like petals next to the violet smelling salts, wrinkled cough-drop wrappers, and crumpled bills. The crumpled bills. Take this and hold it for Marlene until I come out, my mothers mother, whom we called Nana, instructed my other grandmother, as she handed her a small red leather purse containing a crinkled twenty-dollar bill one February day in 1965, just before they wheeled her into an operating room for some exploratory surgery. She had just turned fifty-nine, and wasnt feeling well. My grandmother Kay obeyed and took the purse with the crumpled bill, and true to her word she delivered it to my mother, who was still holding it a number of days later when Nana, laid in a plain pine box, as is the custom, was buried in the Mount Judah Cemetery in Queens, in the section owned (as an inscription on a granite gateway informs you) by the F IRST B OLECHOWER S ICK B ENEVOLENT A SSOCIATION . To be buried here you had to belong to this association, which meant in turn that you had to have come from a small town of a few thousand people, located halfway around the world in a landscape that had once belonged to Austria and then to Poland and then to many others, called Bolechow.

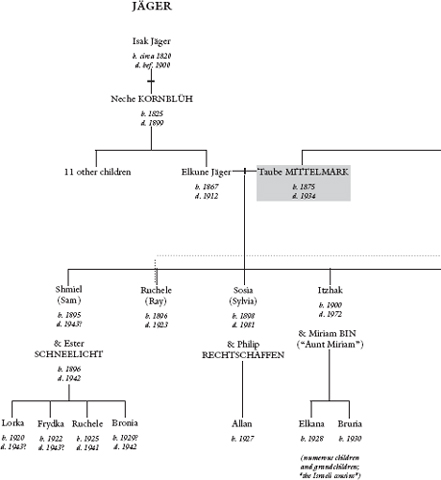

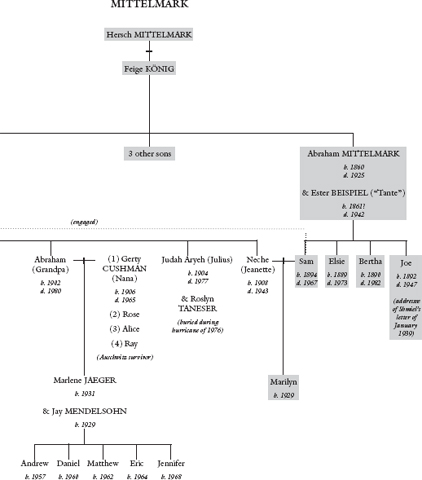

Now it is true that my mothers motherwhose soft earlobes, with their chunky blue or yellow crystal earrings, I would play with as I sat on her lap in the webbed garden chair on my parents front porch, and whom at one point I loved more than anyone else, which is no doubt why her death was the first event of which I have any distinct memories, although its true that those memories are, at best, fragments (the undulating fish pattern of the tiles on the walls of the hospital waiting room; my mother saying something to me urgently, something important, although it would be another forty years before I was finally reminded of what it was; a complex emotion of yearning and fear and shame; the sound of water running in a sink)my mothers mother was not born in Bolechow, and indeed was the only one of my four grandparents who was born in the United States: a fact that, among a certain group of people that is now extinct, once gave her a certain cachet. But her handsome and domineering husband, my grandfather, Grandpa, had been born and grew to young manhood in Bolechow, he and his six siblings, the three brothers and three sisters; and for this reason he was permitted to own a plot in that particular section of Mount Judah Cemetery. There he, too, lies buried now, along with his mother, two of his three sisters, and one of his three brothers. The other sister, the fiercely possessive mother of an only son, followed her boy to another state, and lies buried there. Of the other two brothers, one (so we were always told) had had the good sense and foresight to emigrate with his wife and small children from Poland to Palestine in the 1930s, and as a result of that sage decision was buried, in due time, in Israel. The oldest brother, who was also the handsomest of the seven siblings, the most adored and adulated, the prince of the family, had come as a young man to New York, in 1913; but after a scant year living with an aunt and uncle there he decided that he preferred Bolechow. And so, after a year in the States, he went backa choice that, because he ended up happy and prosperous there, he knew to be the right one. He has no grave at all.

O F THOSE OLD men and women who would sometimes cry at the mere sight of me, those old Jewish people with the cheeks that had to be kissed, with their faux-alligator wristwatch bands and dirty Yiddish jokes and thick black plastic glasses with the yellowed plastic hearing aid trailing off the back, with the glasses brimful of whiskey, with the pencils that theyd offer you each time you saw them, which bore the names of banks and car dealerships; with their A-line cotton-print dresses and triple strands of white plastic beads and pale crystal earrings and red nail varnish that glittered and clicked on their long, long nails as they played mah-jongg and canasta, or clutched the long, long cigarettes they smoked: of those, the ones I could make cry had certain other things in common. They all spoke with a particular accent, one with which I was familiar because it was the accent that haunted, faintly but perceptibly, my grandfathers speech: not too heavy, since by the time I was old enough to notice such things they had lived here, in America, for half a century, but still there was a telltale ripeness, a plummy quality to certain words that were ripe with r s and l s, words like darling or wonderful , a certain way of biting into the t s and th s in words like terrible and (a word my grandfather, who liked to tell stories, often used) truth. Its de troott ! he would say. These elderly Jews tended to interrupt one another a lot on those occasions when they and we would all crowd into somebodys musty living room, cutting off one anothers stories to make corrections, reminding one another what had really happened at this or that vahnderfoll or (more likely) tahrrible time, dollink, I vuz dehre, I rrammembah, and Im tellink you, its de troott .