T

he words critic and critical , which tend to leave a slightly sour taste in the mouth of contemporary American culture (Dont be so critical!; Everyones a critic!), are derived, indirectly, from the Classical Greek word krin , to judge. The noun that comes from that verb, krits , simply denotes a person who makes judgmentsthis being another word that provokes a certain anxiety today. (Who am I to judge?; Dont be so judgmental !) For the Greeks, a krits could be any number of things: an arbitrator in a dispute; a historian (who, according to one Greek author writing in the second century A.D., must approach his raw data in the manner of an interrogating judge in a legal proceeding); an interpreter of dreams; or one of the aesthetic referees who judged the fiercely competitive theatrical competitions held each spring in Athens. The playwright Aristophanes liked to interrupt the action of his comedies in order to make flattering appeals to this or that krits watching the show. Not infrequently, he won.

Critic , then, is a word with a rich and suggestive pedigree. As, indeed, are other words derived from krin , words like criterion (a means for judg

vii INTRODUCTION

ing or trying , a standard ) anda word that you might not have suspected is even remotely related to critic crisis , which in Greek means a separating , a power of distinguishing ; a judgment , a means of judging ; a trial . For what is a crisis, if not an event that forces us to distinguish between the crucial and the trivial, forces us to reveal our priorities, to apply the most rigorous criteria and judge things?

This book is a collection of judgments: which is to say, a collection of essays by a critic. As might be guessed from the foregoing excursion into etymologies, the critic in question has a background in Classics. In the late 1980s and early 1990s I did my graduate work in Greek and Latin, with an eye to a career in academia; instead I became a journalist. This fact will help to explain two important features of this collection.

The first, and less important, is its content. The subjects of many of the pieces collected here, which span a number of genresbooks, theater, films, and translationsand represent most of the fifteen years Ive been writing as a professional critic, have some connection with Greek or Roman culture. There are essays about a movie version of the Trojan War and a steroidal biopic about Alexander the Great; about an updated feminist spin on Euripides Medea and a romanticized drama about the Classics scholar and poet A. E. Housman; about a contemporary verse adaptation, by Sylvia Plaths widower, of a Greek tragedy about a man who treats his wife badly, and a tendentious popular account of the Peloponnesian War. As this list suggests, Ive generally been less interested in writing about classical texts or culture per se than in taking a look at the ways in which popular culture interprets and adapts the Classics not least because of what those interpretations and adaptations tell us about the present, about us. (The Athenians may well have thought that Medea was about language and politics; we think its about desperate housewives.) Only one of the essays here, in fact, is about a book that is scholarly in nature, and that book caught my interest precisely because it attempted to use the Classics as a weapon in a contemporary political battle. Such attempts to use, and abuse, the classical heritage in order to influence mainstream political and cultural discussions, from

INTRODUCTION viii

the conduct of the war in Iraq to the legal status of gay marriage, are the object of more than one judgment in these pages.

A background in the Classics accounts for another, more important and I hope more consistent feature of this collection (which, after all, consists mostly of pieces that have no connection at all to the classical world). When you are exposed for a long time to the astringent beauties of the classical languagesthe hard and unyielding grammars, the uncompromising demands of syntax and exigencies of meter, none of which admit of either shoddiness or approximationyou can develop a taste for a certain kind of rigor; you may begin to seek it elsewhere. To my mind, that rigor serves as a kind of template not only for the method that the critic necessarily applies to his subject (art, theater, film, dance, literature, whatever) but also for the qualities to be sought in the works themselves. Those qualities are: a meaningful coherence of form and content; the subtle but precise deployment of detail in the service of that meaning; vigor and clarity of expression; and seriousness of purpose. Since I see no reason why those standards shouldnt be imposed on (and those qualities sought in) the products of mainstream cultureat least those with aspirations to seriousnessas much as on those of high culture, Ive attempted to seek, and to impose, accordingly in my own critical writing.

Those conjugations, declensions, and meters can take you away from texts altogether; can give you a taste for what you might call the infinite interpretability of thingsnot of this or that book or play (with their hidden coherences, turns of phrase, and elegances of poetic diction, which, armed with your paradigms and dictionaries, you eventually learn to decipher) but of whole cultures. These, too, can in their way be reduced to their essential componentsto their grammars and vocabularies, so to speak. Civilizations, too, can be read. (And judged.) It says something significant, for instance, about the Greek conception of the mind and its activities that hidden in the very old verb oida , to know, is a fragment of an even more ancient word, id , to see. (Its the vid in video .) And it might well say something meaningful about the Greeks and their understanding of the complicated and perhaps inevitably tragic relationship between art, which gives meaning to life, and death (which gives meaning to life in a different way) that the name of that shining god of Art, Apollo, is so closely linked to the verb apollumi , to destroy.

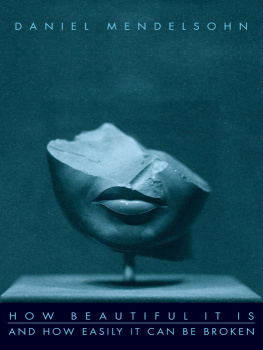

This brings me to my titlewhich, as it happens, has nothing whatsoever to do with the ancient world, although the words in question belong to a writer whom you could certainly characterize as the twentieth centurys answer to Euripides: a modern playwright who, like his ancient antecedent, had a particular genius for creating memorable heroines as mouthpieces for universal human emotions.

How beautiful it is and how easily it can be broken is a quote from the stage directions to a play by Tennessee Willliams, a great American drama about the victimization of a fragile girl who is tragically in love with beautiful, breakable things: the famous glass menagerie that gives the play its title, and which of course provides a richly useful symbol for the themes of delicacy and brittleness, of the lovely illusions that can give purpose to our lives and the hard necessities that can shatter them. Interestingly, Williamss phrase occurs in a stage direction not about the plays set design but about a certain musical leitmotif he has in mind, one that (he writes, in his typically meticulous directions)

expresses the surface vivacity of life with the underlying strain of immutable and inexpressible sorrow.... When you look at a piece of delicately spun glass you think of two things: how beautiful it is and how easily it can be broken. Both of those ideas should be woven into the recurring tune.