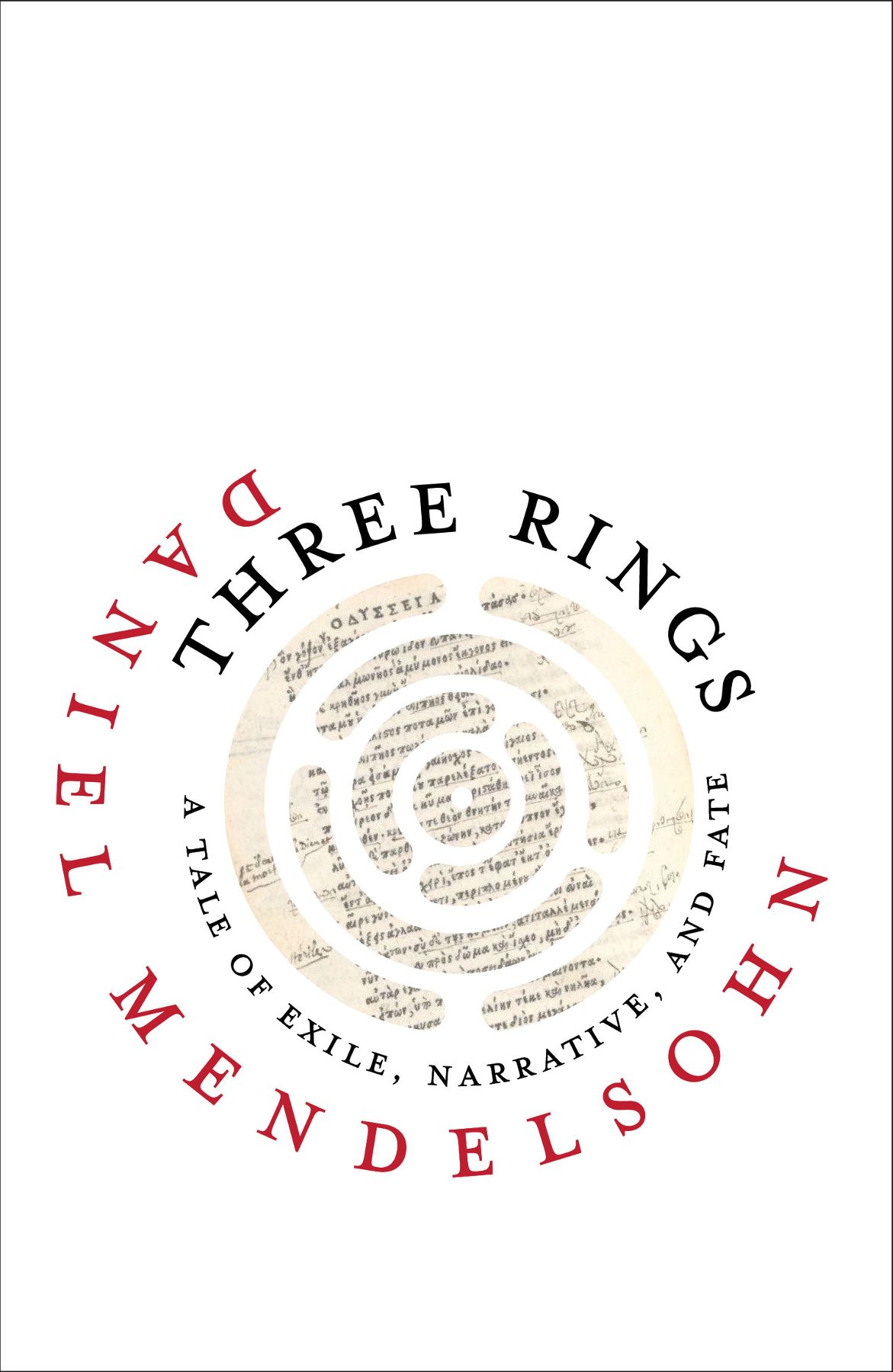

Daniel Mendelsohn - Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate

Here you can read online Daniel Mendelsohn - Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: University of Virginia Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Virginia Press

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Daniel Mendelsohn: author's other books

Who wrote Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ALSO BY DANIEL MENDELSOHN

Ecstasy and Terror: From the Greeks to Game of Thrones

An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic

Waiting for the Barbarians: Essays from the Classics to Pop Culture

C. P. Cavafy: The Unfinished Poems (translation)

C. P. Cavafy: Collected Poems (translation)

How Beautiful It Is and How Easily It Can Be Broken: Essays

The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million

Gender and the City in Euripides Political Plays

The Elusive Embrace: Desire and the Riddle of Identity

UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA PRESS

Charlottesville and London

Page-Barbour Lectures for 2019

University of Virginia Press

2020 by Daniel Mendelsohn

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2020

ISBN 978-08139-4466-1 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-8139-4467-8 (ebook)

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title.

Cover art: Page from Greek edition of Homers The Odyssey (Omerou Illias = Homeri Illias, vol. 2 [Venice: Aldus, 1504]). (Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

For Glen Bowersock and Christopher Jones

Tu se lo mio maestro e l mio autore;

tu se solo colui da cu io tolsi

lo bello stilo che mha fatto onore.

PART 1

PART 2

PART 3

Il valente uomo, che parimente tutti gli amava, n sapeva esso medesimo eleggere a qual pi tosto lasciar lo dovesse, pens, avendolo a ciascun promesso, di volergli tutti e tre sodisfare; e segretamente ad uno buono maestro ne fece fare due altri, li quali s furono simiglianti al primiero, che esso medesimo che fatti gli avea fare appena conosceva qual si fosse il vero.

The worthy man, who loved them all alike and knew not himself how to choose which one he ought to leave the ring to, considered that, having promised it to each one of them, he should like to satisfy all three; and in secret he had a master craftsman make two other rings which were so similar to the first that he himself, who had ordered them made, scarcely knew which was the true.

B OCCACCIO , The Decameron, Day 1, Third Novella

A STRANGER ARRIVES in an unknown city after a long voyage. He has been separated from his family for some time; somewhere there is a wife, perhaps a child. The journey has been a troubled one, and the stranger is tired. He stops before the building that is to be his home and then begins walking toward it: the final short leg of the improbably meandering way that has led him here. Slowly, he makes his progress through the arch that yawns before him, soon growing indistinguishable from its darkness, like a character in a myth disappearing into the jaws of some fabulous monster, or into the barren sea. He moves with difficulty, his shoulders hunched by the weight of the bags he is carrying. Their contents are everything he owns, now. He has had to pack quickly. What do they contain? Why has he come?

FOR A PERIOD of several years early in the new century I was working on a book the research for which required me to travel extensively throughout the United States, Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, Israel, and Australia. I went to those places in order to interview a number of survivors of, and witnesses to, certain events that took place during the Second World War in a small eastern Polish town where some relatives of mine had lived. These relatives were ordinary people, of little interest to history but nonetheless the focus, the center so to speak, of the story I wanted to tell, about who they had been and how they had died; just as the town itself, a place of little historical importance, had yet been the focus of my relatives lives, the fixed point from which they had never wanted to stray. And so they died there, some hidden quite close to the house where they had lived, only to be betrayed; some rounded up and shot in the town square or in the old cemetery nearby; some transported to remote locales and then gassed. From this small place the few survivors would later radiate outward, after the war was over, to distant parts of the worldplaces that, only fifteen years earlier, would have struck these townspeople as improbable, absurd even, as destinations, let alone as places to live: Copenhagen, Tashkent, Stockholm, Brooklyn, Minsk, Beer Shevah, Bondi Beach. Those were the places I had to go, sixty years later, in order to talk to the survivors and hear the tales they had to tell about my relatives. The only way to get to the center of my story was by means of elaborate detours to distant peripheries.

When I was finished writing the story I found myself unable to move. At the time, I told myself that I was merely tired; but now the distance of a decade and a half permits me to see that I had experienced a crisis of some kind, even a kind of breakdown. For some months I found it hard to leave my apartment, let alone to do any traveling. I had been to Australia and Denmark and Ukraine, Israel and Poland and Sweden, been to the mass graves and to the museums, including one in Tel Aviv where, to my surprise, the thing that moved me most was a room full of meticulous models of synagogues that had, over the millennia, been built throughout the territory of the Jewish diaspora: in Kaifeng, China, and in Cochin, India, the sixth-century Beth Alpha Synagogue in Lower Galilee and the twelfth-century Santa Maria la Blanca Synagogue in Toledo (which owes its strange name to the fact that, shortly after it was built by a special dispensation from King Alphonso X to create the largest and most beautiful synagogue in Spain, it was attacked by mobs, partly destroyed, and subsequently reconstituted as a church dedicated to the Virgin); the nineteenth-century Tempio Israelitico in Florence and its contemporary the Oranienburger Strae Synagogue in Berlin, both largely destroyed by fire in 1938 and now painstakingly re-created in miniature in Israel, a country that did not exist when those buildings were gutted. I was so moved, I think, because at one point from late childhood to early adolescence I myself had been an obsessive model-builder, carefully constructing precise scale replicas of ancient buildings, the mortuary temple of Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahri, the Parthenon in Athens, Romes Circus Maximus, each of those structures characterized, as I can now see although I doubt I was conscious of it at the time, by the insistent reduplication of a given structural or decorative element: ramps, columns, arches. I suppose I found the repetition reassuring. At any event, this is why, as I stood there in the model room of the museum in Tel Aviv, halfway through the worldwide journey I undertook in the early 2000s, I had such a strong emotional reaction. I was familiar with the impulse to make such replicas, which is haunted by a poignant paradox: the belief in our ability to re-create and the acknowledgment that the original has been lost... Lost, I should say, can be a misleading word, implying as it does destruction beyond the point where reconstruction is possible. But there are other kinds of loss, alterations or repurposings of structures so extensive or dramatic that, although the original still stands, is still present, we might nonetheless feel the need for reconstruction of the sort to be found in the Model Room at Beth Hatefusoth in Tel Aviv. There is, for example, a decaying but still handsome structure that dominates the market square of a small sub-Carpathian town called Bolekhiv, currently located within the borders of Ukraine although it was part of Poland when my relatives, who called it Bolechw, lived there, as their relatives before them had done for many centuries until 1943, when the last of them perished. This large rectangular building, its pale pink stucco walls pierced at regular intervals by a series of elegant tall windows with rounded tops, was once known as the Great Synagogue of the towna slight pretension that can be forgiven when you consider, first, that there were at one time more than a dozen synagogues of various sizes in this small market town, and, second, that most of the other buildings in Bolechw were in fact quite small in comparison. The epithet Great can, if anything, strike you as poignant now, given that there is not a single synagogue left in that place and that every single person who ever attended those houses of worship, every person who ever familiarly referred to this structure as the Great Synagogue, is long since dead; and that almost none of the people who live there now are aware that it was once a place of worship. This is not surprising. In the 1950s, long before the vast majority of the current residents lived there, the building had been converted into a meeting house for leather-workers, its walls painted with murals celebrating the landscapes of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and a decade before that the ark of the Torah, once the focal point of its architecture, had been ripped out, its scrolls defiled and lost, its decorations stripped off. Hence although you could say that the Great Synagogue of Bolechw still stands, it seems nonetheless to have been lost, seems to be in need of a model that could show you what it looked like when it was first constructed, the product of a living civilization. The historical reality which a model of an old building is meant to suggest is, therefore, more than merely material; such a model is surely meant to capture the (as it were) soul as well as the appearance of a building... But all this is a dream. There is no model of the Bolechw synagogue in the Beth Hatefusoth Museum, partly because no one who could help reconstruct its lost reality is alive today, and partly because if the museum were to re-create in miniature every synagogue in every town in Eastern Europe that suffered the same fate as the synagogue in Bolechw, it would take up acres, rather than a single room, in Tel Aviv.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate»

Look at similar books to Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.