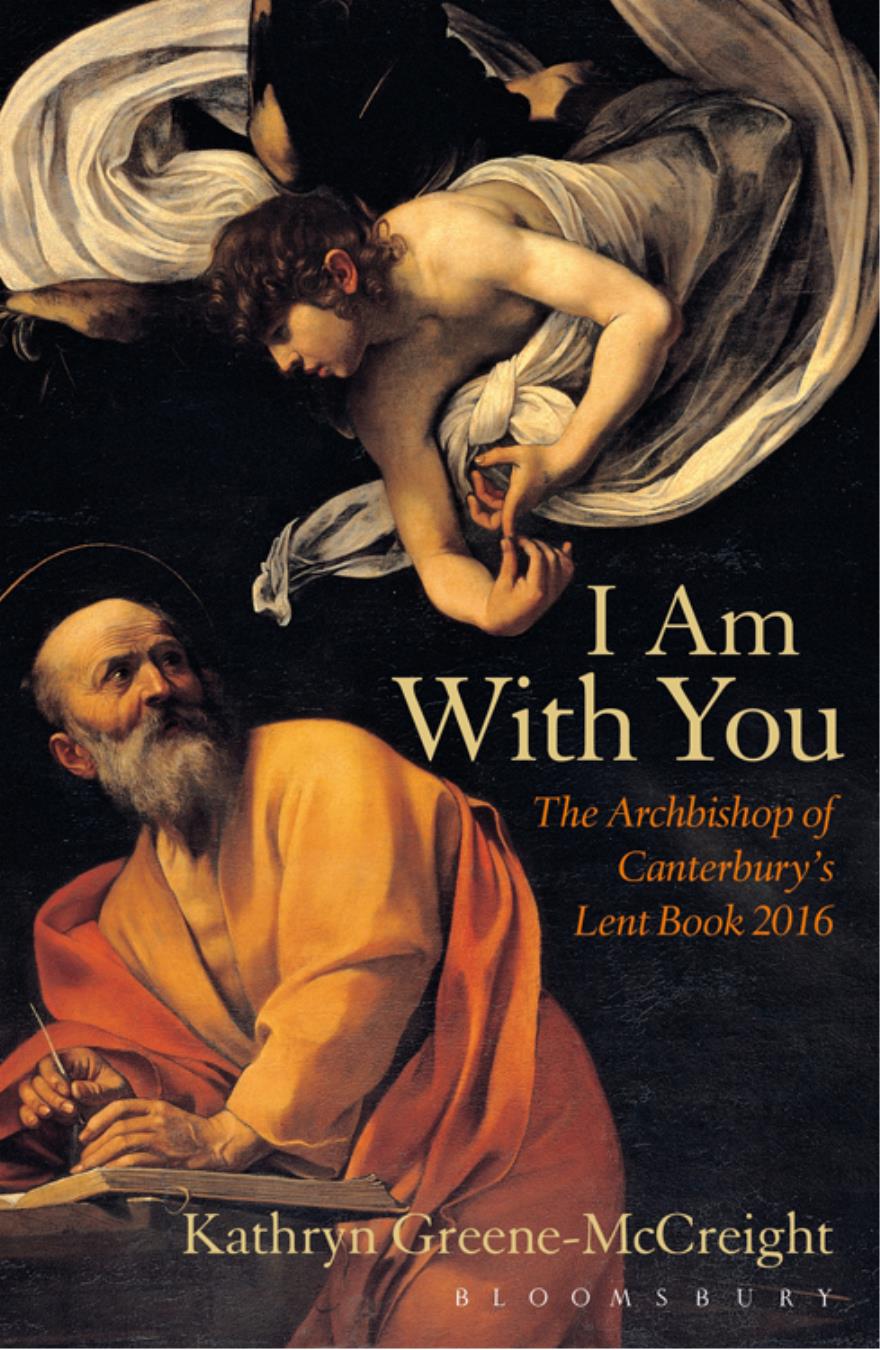

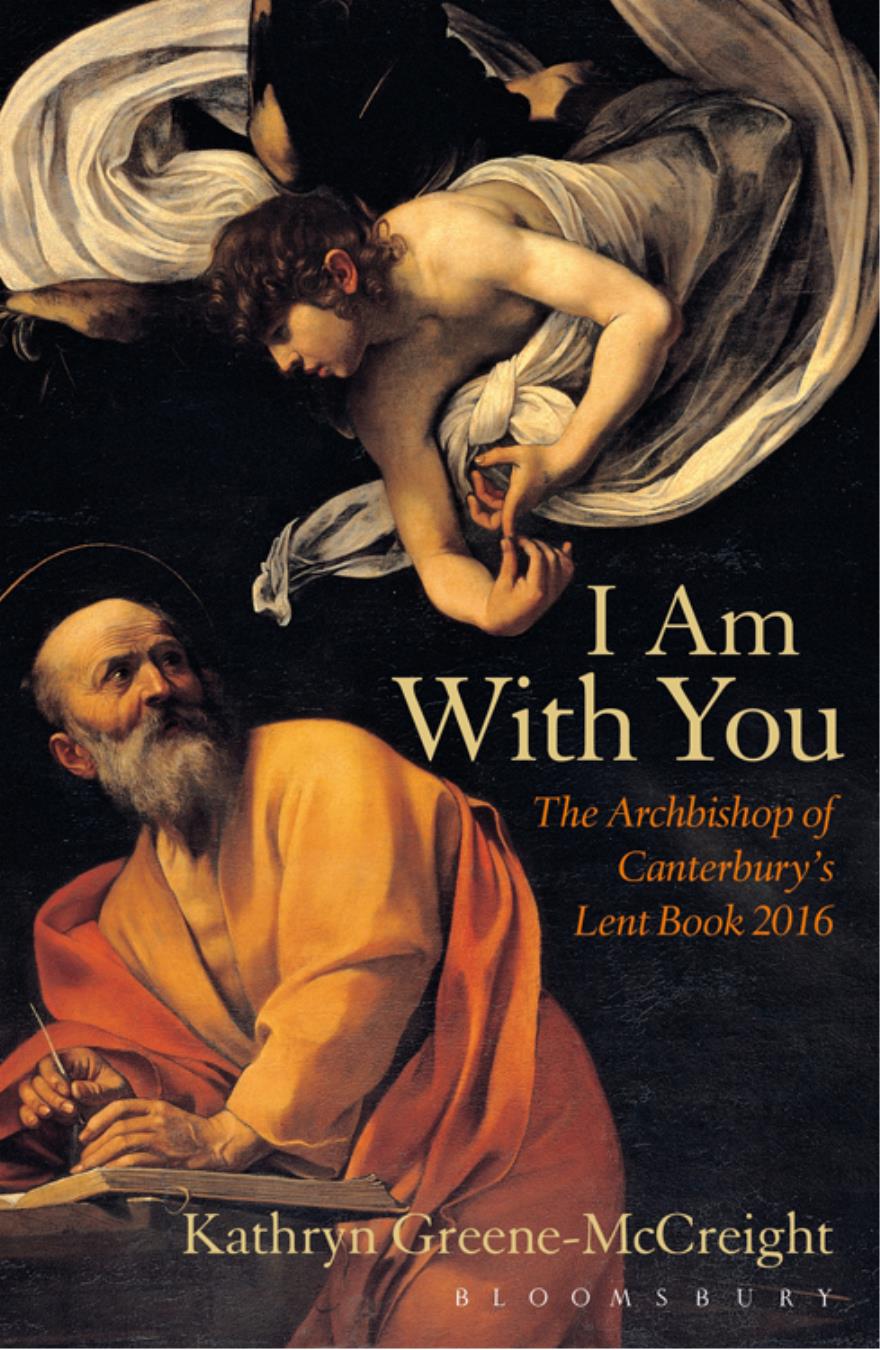

I AM WITH YOU

The Archbishop of Canterburys

Lent Book 2016

KATHRYN

GREENE-McCREIGHT

I first came across Kathryn Greene-McCreight when I read her book, Darkness is My Only Companion. It is a personal account of her struggle with depression and a theological reflection on the nature of mental illness. For me, it was one of those rare books that reshapes the understanding. Its utter transparency and integrity moved me deeply, while its sophistication and profundity sparked some fruitful thinking.

So when a few days later I was wondering who might write the Lent book for 2016, Kathryns name jumped readily to mind. Others involved in the process felt equally positive about the choice, and the book entirely fulfils my hopes in asking Kathryn to write it.

Its a very different kind of book; Kathryn is no one-trick pony. This is a meditation for Lent on Gods presence, light and darkness, all set in the context of the Offices of the Benedictine day.

It is a book that operates on a number of levels. Each chapter can stand alone. For devotional use in Lent, Id recommend that the chapters are taken a week at a time.

It is beautifully written: the thoughts unfold gently before the eyes as one reads. They lead us inexorably back to the heart of orthodox Christianity: which is not a set of dogmatic or doctrinal propositions, nor a way of life, let alone a set of rules although there are aspects that spring out of the richness of the Christian life in each of these areas. It is about the lived experience of the presence of God in all circumstances and all times, including everything that life can throw at us.

As such, this book is about growing closer to God. That is at the heart of a good Lent. We come to a time of fasting, discipline and study, in order that we may renew our knowledge of His presence. That involves a stripping of those things that divide us from God, developing our obedience to His call and venturing deeper into the fire of His love.

The themes of light and darkness, and the use of the pattern of the Offices, give contrast and stability to the unfolding chapters. Through the book we travel through day and night, the reality of human experience lived through our lives. At the end the dawn brightens with the hope and certainty of resurrection, the knowledge that in the grace and love of God we are called to eternal life with the one who smashes down the barriers of death.

As well as contrast and the stability of the Offices, there is the interaction with God. How does He come to us and speak to us? Sometimes it is through messengers and angels; sometimes it is through His revealed presence; sometimes it is through the changes and chances of life in all its challenge and complexity.

Someone once described to me two preachers: one who sounded sophisticated, yet the more you thought about it the less there was; and the other who sounded simple, yet the more you thought about it the more there was. Kathryn is in the latter category. This is a book to be picked up and put down quietly, not read at a sitting or in a rush. Where something is too demanding, I recommend that you move on and come back to it. The book gives one permission to say, Im not quite there yet.

As with the rhythm of Benedictine life in the monastery, the Offices repeat themselves day by day. After a week, one may feel to have seen virtually all there is. That is the point at which the growing really begins: the process of deepening is through repetition.

I trust that as you read and reflect on this book you will find that deepening. It will bring you to the glorious dawn of Easter, filled with confidence and joy.

+Justin Cantuar

Lambeth Palace

Feast of the Transfiguration, 2015

Lent is traditionally a time of self-examination and repentance as we prepare for Easter and the resurrection of Jesus. If we think of Easter as light, we might think of Lent as preparing our eyes to behold that light. Light helps us see where we are headed, but sometimes it can hurt our eyes.

Imagine going from a completely darkened room immediately into bright daylight. We might shield our eyes as we become accustomed to the light. Gradually exposing ourselves to light keeps us from squinting in pain. Here is Gods mercy: the sun rises slowly. It could have been different, I suppose, but the disciples find the tomb empty in the morning. The darkness is slowly conquered as the rising sun leads in the morning. Only then do the disciples behold the Light of the World. It is for this Easter light that we prepare the eyes of our souls during Lent. We move from morning through the daytime, past the night, beyond the dawn to the morning of the resurrection.

In order to recognize the presence of God in light, as did the disciples on that first Easter, we might try first to learn about the identity of the Risen One. How do we do this? We turn to Scripture. There we are guided in discerning the identity of the One who greets us in the resurrection light of the New Creation. As Paul says, on the last day the trumpet will sound and the dead will be raised, and we shall all be changed (1 Cor. 15.52). Easter is a foretaste of that last day, of that trumpet call, of that New Creation.

But first, a word on what it might mean for us to make such a bold claim that God could be present.

Bidden or Unbidden, God is Present

Carl Jung (18751961), the father of analytic psychology, would probably approve of our title, I Am With You. Among other things, he thought that we humans are fundamentally religious beings. Exactly what Jung understood by the word religious is not clear to me. I do have a clearer sense, though, of what religion, for him, was not.

Apparently, during his graduate studies, Jung was rummaging through collections of Latin proverbs. A saying by the Humanist scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam (14661536) struck him in particular: Vocatus atque non vocatus, Deus aderit. We might translate this into English as Bidden or unbidden, God is present, or maybe more loosely as Whether you like it or not, God is here. Jung affixed this quotation over the door of his home in Zurich, and it is said that these were his last words. The proverb is also carved on his tombstone.

Ironically, these words seem to have come from a yet earlier source. What is far more interesting, though, is that the proverb is often translated by Jungs followers as Bidden or unbidden, the god is present. While this may indeed have been Jungs understanding of Erasmus, I seriously doubt that Erasmus himself would have approved of such a translation. For Erasmus Vocatus atque non vocatus, Deus aderit would not have referred to a generic deity (the god) but to the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the God of Jesus Christ.

Jung was a man of his age, just as Erasmus was a man of his. And our own age, in turn, inherits in many ways, more from Jung than from Erasmus. Like Jung, we often choke on the scandal of particularity. We, too, tend to prefer universal ideas rather than specifics. With regard to Jesus, this preference is expressed in Judas mocking song in the 1970s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar by Andrew Lloyd Webber: If youd come today you would have reached a whole nation; Israel in 4 BC had no mass communication. Specificity is so limiting. For us modern folk, the idea that God is in the details is more of a problem than we may think.

Next page