Introduction

by Janwillem van de Wetering

This is one of the main books that got us, Zennies, all started, this is one of the Model-A Fords of Western Ch'an Buddhism.

(Sanskrit Dyana = Chinese Ch'an = Japanese Zen = regular meditation)

An age ago, in a former existence, many dreams back now, I came across this splendid vehicle at Foyles, Charing Cross Road, London, a bookstore spread through five multi-storied houses. There was an old man in the philosophy basement, a sage in suspenders, who watched my dismal perusal of Hume, Jaspers and Heidegger. The salesman/sage wanted to know what the young gent was after.

I said I wanted to know why life is a pain.

Why would the young gent want to know why life is a pain?

Why, to put an end to the pain, you old codger.

That was the right attitude, the old codger said, and sold me a D.T. Suzuki.

Delirium Tremens Who?

That was right, the old codger said. All Zen sages are out of their minds, but the actual name was Daisetz Teitaro.

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, I made a mantra out of the sounds and danced to them in my room at Hammersmith Terrace, with a view of the Thames, then still muddy.

The Thames got cleaned up since then.

And so did I, some, maybe, it seems. And countless other I's.

If sothanks to Suzuki.

How does one clean up the I? By doing away with the I.

By seeing through the sucker.

There are koans to that effect, as Dr. Suzuki points out in this textbook.

Read a koan, the salesman/sage told me. Go on, open the book, pick any koan.

Gent: I worry.

Codger: Show me this I that worries.

Gent: I can't find it.

Codger: See?

I laughed. This was fun, better than the hairsplitting of analytical philosophy that redefines life=pain, after a long academic merry-go-round, a degree or two, a career, birth-middlelife crisis-death, into life=pain without ever showing a way out, except by suicide maybe.

But does suicide put an end to life=pain?

Doesn't suicide rather lead to more suffering in the bardos, after-earth limbos where we still carry names, identities, worrying I's?

What else can the astral spheres be than more pseudo-substantial hells where we are still looking for the light, while we are the light?

Heed Allen Ginsberg who sang, squeezing his harmonium May 1994: die when you die.

Codger Ginsberg sang through the Sony speakers, all over Sheep Meadow, (Central Park, Manhattan, New York, USA, World, Just Another Universe, Void) that we should die when we die.

No kidding. Let our I's die.

"But," Sariputra asks, "how to do that?"

We all know it now, there are five million Buddhists in the western world, cracking their koans.

(What's a koan again? A 'public case.' A case, a non-intellectual publicnothing exclusive hereriddle that anyone solves instantly, when the time is there.)

The year was 1958 when Suzuki's book found me. I was reading existentialism at University College but the despair of western egocentric doomthought depresses.

Sartre (I read) says: "We are condemned to freedom."

But surely that can't be right. Why should freedom be a burden, and if it is, shouldn't we throw it away?

"How to throw away burdensome thinking of make-believe-freedom?" asks Sariputra.

"Read me first" the Suzuki book says.

Eat me (like Alice in wonderland eating the pills: they made her grow with joy and learning, they made her shrink with joy and insight, prepared her for the Caterpillar: "WHO, ALICE, ARE YOU?' Then made her waft away into the Cheshire Cat's smile).

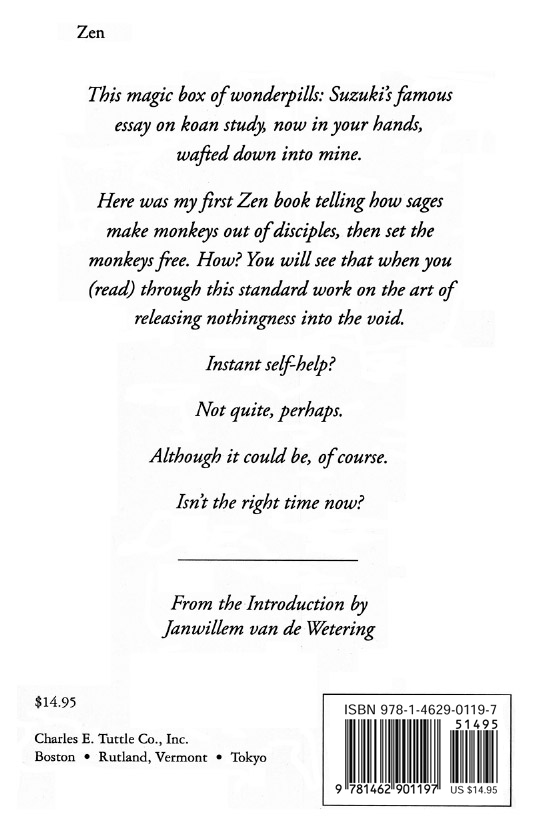

This magic box of wonderpills: Suzuki's famous essay on koan study, now in your hands, wafted down into mine.

Here was my first Zen book telling how sages make monkeys out of disciples, then set the monkeys free. How? You will see that when you plow (vintage Suzuki ain't easy reading, there is a culture difference to start off with) through this standard work on the art of releasing nothingness into the void.

Instant self-help?

Not quite, perhaps.

Although it could be, of course.

Isn't the right time now?

When I entered Daitoku-ji monastery, Kyoto, Japan, clutching Suzuki in my right armpit I asked the one and only English speaking monk how long koan study takes.

He said he was the Buddha's ape, what did he know?, but that sixteen years sounded like just about right.

There are some 1700 koans, this doorman to wisdom explained, but a lot of them are copies or variations and you can squeeze the program into a mere hundred, with three big ones up front. Once, he let me know right there and then, once you answer the big ones, the little ones fall in place easily. Sogive and take a bit of time for genius or abysmal ignorancesixteen years is about the right time span. (I would be a roshi in my forties.)

Then, when I had enough Japanese, I asked the monastic teacher, and he laughed.

Zen teachers laugh a lot, especially during sanzen.

You can, in their private quarters, (at 3:30 a.m.) ask them what's so funny and they will tell you, in their own fine way.

I was already there, the Zen teacher laughed. I had always been there. There was nothing to obstruct me. Did I know the Heart stra? No? He would sing it for me.

Sariputra, form is not other than emptiness

and emptiness is not other than form

form is precisely emptiness, and emptiness precisely form.

Who is Sariputra? I asked.

Sariputra was sent back to the Zendo, to more form, to more pain, more autumn flies dying heavily on my clasped hands, more smoldering of leg joints, more sadistic arrogance stupidly staged by stick-bearing holyboly office holders.

Sariputra is the Bodhisattva who starts off learning by reading books by D.T. Suzuki.

I actually met Dr. Suzuki in Japan, or he met me, or, rather, he looked at me. Ruth Fuller Sasaki, and American Zen priest, restored Ryosen-an temple and added a Zendo, gift of her First American Zen Institute to the Daitoku-ji compound. The Zendo got filled up with foreign dogs, sycophants and monkeys. I sat and sufferedsuddenly the doors flung open, the venerable Mrs. Sasaki, outside, beamed, the Zen scholar Suzuki, outside, raised tufted Zen master eyebrows.

Us monkeys, inside, blinked.

"Look what I've done, D.T."

"Well done, R."

Well done indeed. Build Zendos, write books, chant the meditation-rock stra in Central Park, compose an introduction, all to find the way out.

And thanks to Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki for pointing.

Surry, Maine, May 1994

THE KOAN EXERCISE

AS THE MEANS FOR REALIZING

SATORI OR ATTAINING