Contents

This second volume on the Fatimids has richly benefited from several colleagues at the IIS: Dr Hasan al-Khoee, Tara Woolnough, Lisa Morgan, Russell Harris, and Sarah Campbell, who have shepherded the text through various stages of its production. My sincere gratitude to Dr Shiraz Kabani for a lifetime of friendship and support. Shahnavaz, Adil, and Nabila you are the beacons of my life.

In the interest of readability, notes have been kept to a minimum, with primary-source quotes referenced in the endnotes. Similarly, diacritics for transliterated words have been limited to the ayn () and the hamza () where they occur in the middle of a word. The words ibn and bint meaning son of and daughter of respectively are abbreviated to b. and bt. when occurring in the middle of a name. All dates are Common Era, unless otherwise indicated. Supplementary material related to the content of the book is available on the IIS website: www.iis.ac.uk

There are moments in history when the past, the present, and the future seem to clash at an accelerated pace, as if fired through a hadron collider, resulting in epochal changes in human civilization. Such significant events whether the onset of the First and Second World Wars, the independence movements in Asia and Africa, or the collapse of the Soviet Union were understood as being transformative by those who lived through them, long before later historians pronounced their judgement.

In the few years that have elapsed between the publication of TheFatimids: 1. The Rise of a Muslim Empire and this second volume, much in the world has been irrevocably transformed. Amidst fractious social, economic, and political convulsions, humankind has witnessed tangible signs of its wilful neglect of the environment and has faced a stark reminder of its own fragility in the face of a global pandemic.

Through all such epochal transformations, one distinct feature of the human experience remains constant: our inclination to look to the past to make meaning of the present. This impetus animated the Greek historians of the third century BCE just as it did the Church fathers between the first and eighth centuries. It galvanized pioneers of Muslim historical literature in the 9th and 10th centuries and their successors in the medieval period, and it animated the works of early modern historians of 18th- and 19th-century Europe. Today, it shapes both popular and academic history writing, including this book.

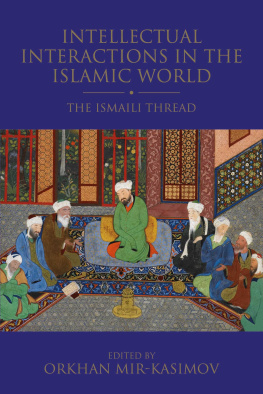

The establishment of the Fatimid caliphate in the 10th century was arguably one such moment of significant transformation in the medieval Muslim world. This is attested by the indelible imprint it made on Islamic history, thought, literature, art, architecture, and aesthetics over the two-and-a-half centuries of its existence (909 to 1171). The period continues to elicit significant interest across various disciplinary fields to this day.

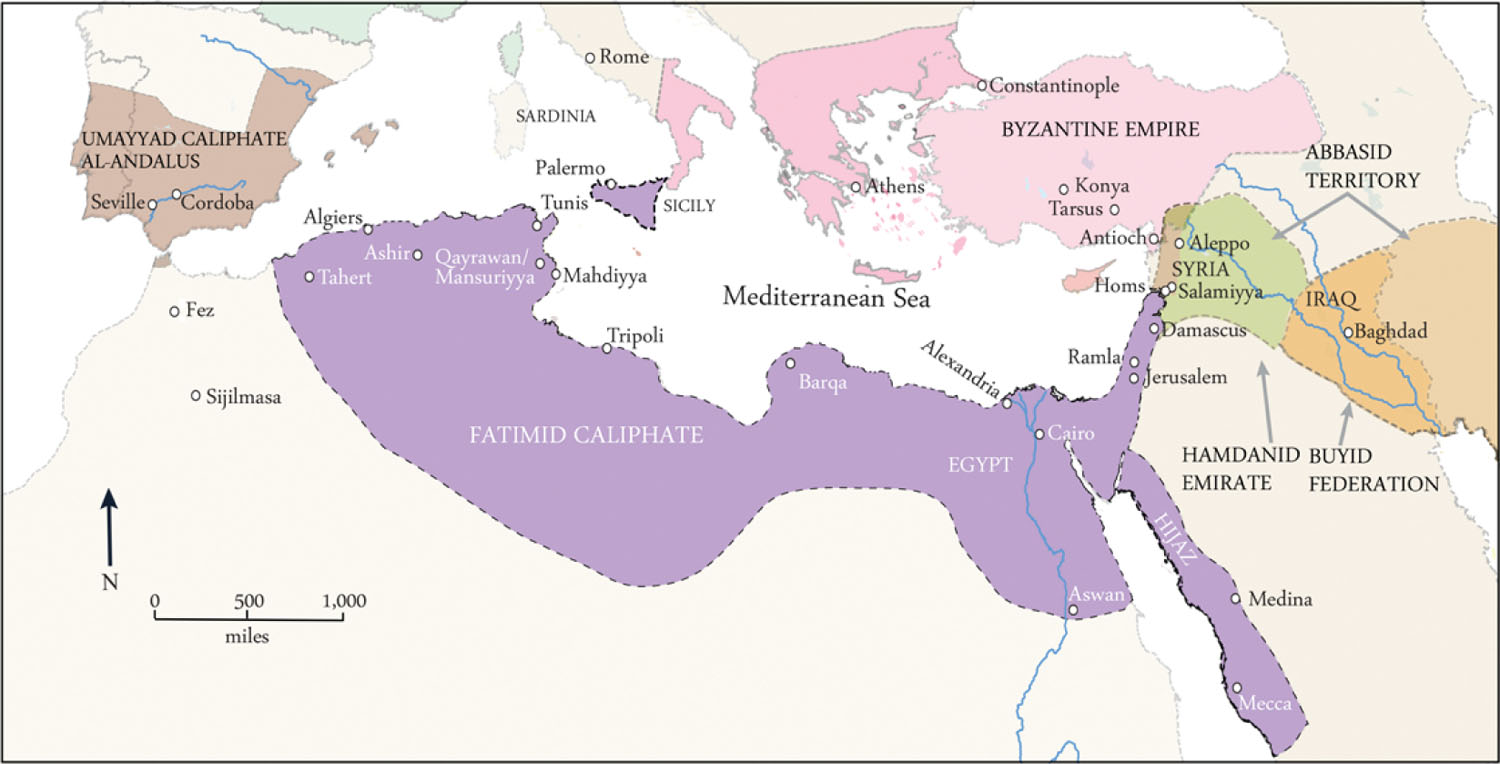

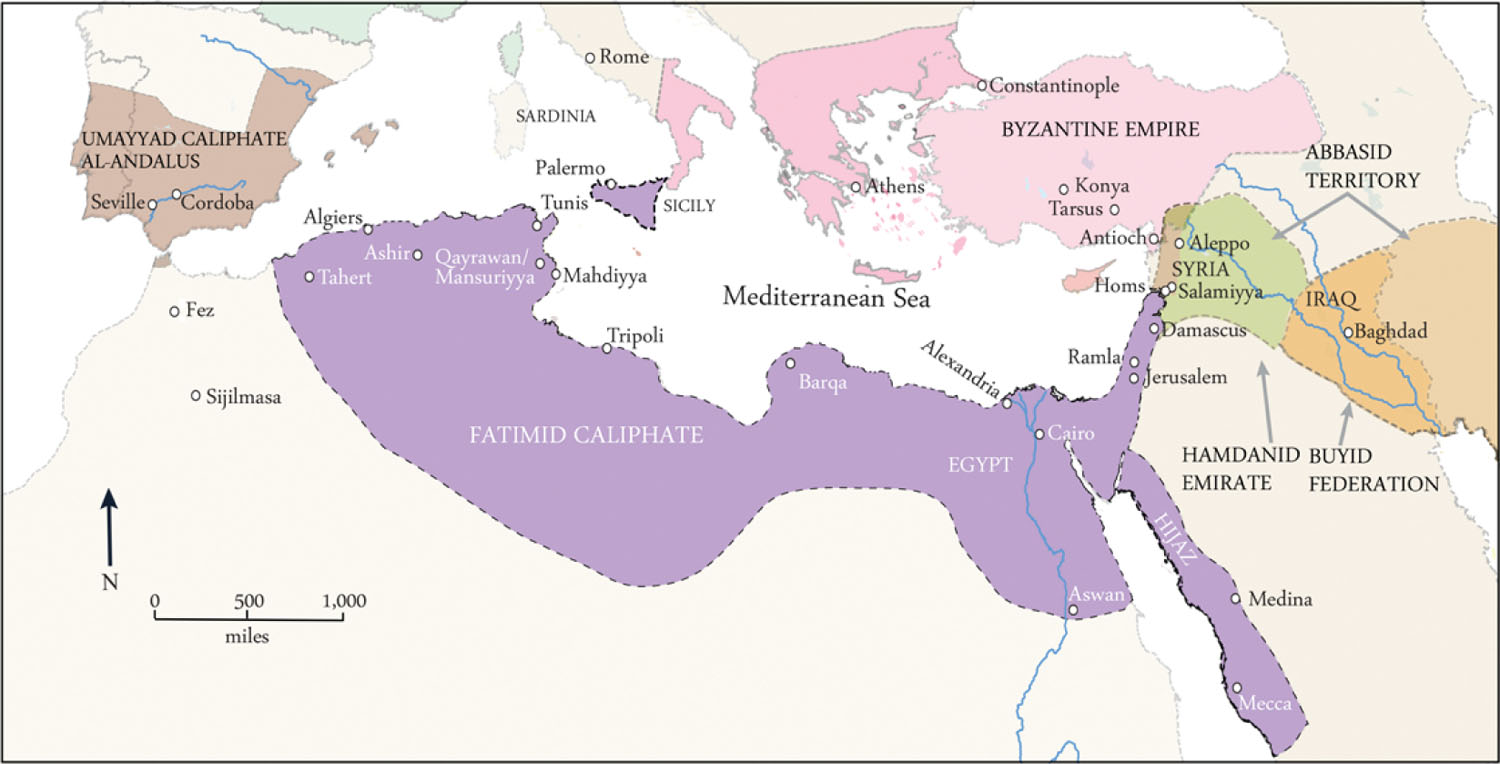

Led by a hereditary succession of Imams (authoritative religious guides), the Fatimids proclaimed their descent from the Prophet Muhammad (d. 632) through his eldest daughter Fatima (d. 632) and his cousin and son-in-law, Ali b. Abi Talib (d. 661). The Fatimids religious and political authority was manifested in their establishment of the first Ismaili Shii caliphate to rule over the heartlands of the Muslim world. From 909 to 973 the subject of volume 1 of this work Fatimid rule was centred in North Africa and along the Mediterranean littoral. From 973 to 1171 the focus of this volume the Fatimid caliphate evolved from a provincial dynasty in North Africa to a thriving Mediterranean Empire centred in Egypt. Their settlement in the country transformed Egypt from what had already been a lucrative regional province under previous administrations to the capital hub of an empire for the first time in a millennium.

During this second phase of their history, the Fatimids founded Cairo and oversaw its development into a major cultural and economic nexus linking Asia, Africa, and Europe. The empires affluence engendered a vibrant cultural, artistic, and intellectual milieu, reflecting the broader civilizational lan of the age. The Fatimids marshalled significant developments in statecraft and civic life. However, they also had to contend with political and ideological rivalries from the neighbouring Abbasid, Umayyad, and Byzantine Empires, as well as the challenges of governing a multi-ethnic populace consisting of multi-denominational communities from the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish faiths. They weathered these challenges by developing inclusive approaches to governance, administration, and the judiciary, which allowed for the largely peaceful co-existence of communities within their realms. The Fatimids also patronized public ceremonials that venerated the Prophet and his family (his ahl al-bayt); these commemorations remain a feature of devotional practice in many Muslim societies today.

The formation of the Fatimid caliphate also marks a watershed in the religious history of the Muslim world, particularly in the history of the Ismaili Shii community. For the Ismailis, the Fatimid Imam-caliphs were part of a continuum of divinely designated Imams descended from the family of the Prophet Muhammad. In Ismaili Shii doctrine, the imamate began when the Prophet in 632, at Ghadir Khumm, shortly before his demise declared his cousin and son-in-law Ali b. Abi Talib the first Imam. The Nizari Ismailis believe the succession of Imams in direct descent from Imam Ali and Hazrat Fatima continued from the seventh century, through to the Fatimid Imam-caliphs, and on into the present day to the 49th Imam-of-the-Time, Shah Karim al-Husayni (b. 1936). Today, the Ismailis are the second largest community of Shii Muslims, after the Ithnaasharis, and they reside across the Middle East, South and Central Asia, East and South Africa, as well as in Europe, Canada, and the United States.

An important concept in early Muslim intellectual traditions centred on the idea of the turning of time. This was encapsulated in the Arabic term dawla literally the turning of a cycle which, having been used to denote the successful alternation between one ruling power and another, came by the 10th century to denote a dynastic state. The use of dawla to mean a government remains widely used in the Arab world today. For many medieval Muslim writers, the Fatimid dawla was thus a new turn in the political history of the region, whose era replaced that of earlier dawlas. The Fatimids themselves conceived of their polity as the dawlat al-haqq the rightly guided state in which principles of legitimate authority and justice were to underpin their governance over the Muslim world. In our 21st-century era of turns and transformations, the history of the Fatimids provides a reading of how past communities developed creative responses to the rhythms of continuity and change in human society.

Presenting a comprehensive account of over two centuries of complex and dynamic Fatimid rule in Egypt in a slim volume is a tall order. However, the book aims to provide the major contours, figures, and developments that shaped the course of the Fatimid age in Egypt, thus enabling non-specialist readers to develop an understanding of this critical era of Muslim and Mediterranean history.

Next page