Transregional Practices of Power

Edited by

Milinda Banerjee

Julia C. Schneider

Simon Yarrow

Volume

ISBN 9783110689341

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110690118

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110690187

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

For all those who lost their lives in the servitude of empires

Preface

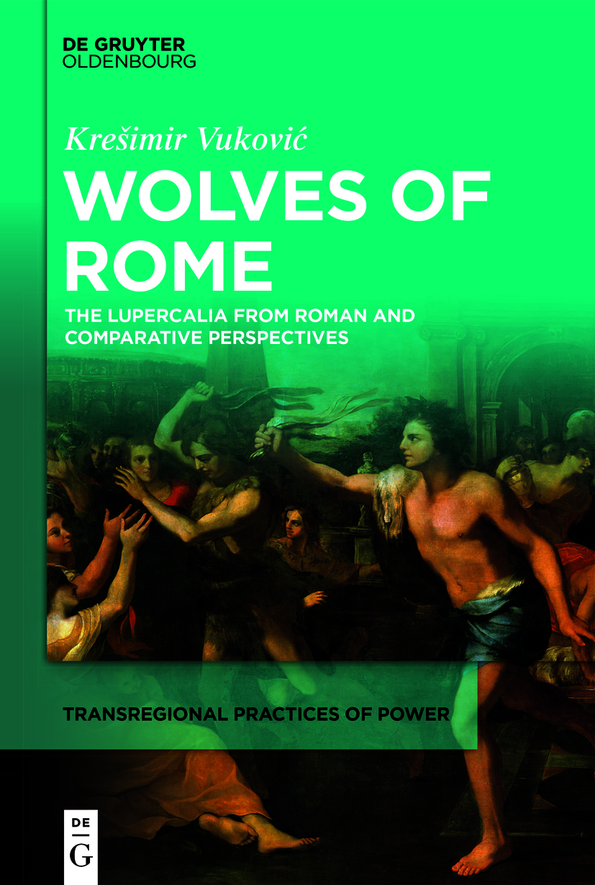

This book is a revised, expanded, and updated version of my doctoral thesis, defended at the University of Oxford in July 2015. The focus of my thesis was the Roman festival of the Lupercalia, which remains the focus of the book. The Lupercalia has fascinated me ever since I was an undergraduate student, but I chose it to be the topic of my doctoral thesis almost by accident. Only in hindsight did I come to realize that my interest in the Roman festival of young naked Luperci grew alongside my acceptance of my identity as a gay man. (I say this with the awareness that many will use it to dismiss the book as a serious study.) But the Lupercalia was not all fun and games. The festival has a long history that spans not only all the periods of ancient Rome, but also connects to other cultures, particularly Indo-European ones, and this was often misused by right-wing scholars.

The term Indo-European is a construct that various ideologies have used for over two centuries starting from colonial India, where the British first invented the term. Classicists may be surprised to see it carries so much weight in this book. I believe that the discipline needs to open itself up and to look beyond its traditional Greco-Roman canon to include other ancient cultures. The various traditions classed under the linguistic term Indo-European provide just one of the many ways in which a more balanced perspective can be attained. It is not surprising that Indo-European studies have been heavily abused by imperialists and fascists. The search for Indo-European roots and causes involves a degree of speculation that goes far beyond the written record and into the realm of mythology. As the book unfolds, it will become more clear that I propose new ways to fill the spaces of this prehistoric time. Old imperialist projections cannot simply be discarded with nothing to replace them. I am not the first to argue that our present age requires us to find new ways of conceiving of the environment and the place of human animals in the wider web of life (to use Alexander von Humboldts term). I believe that ancient mythologies have much to offer in this regard and I find that the Vedas provide a necessary counterweight to the Greek and Roman classics. The story of the Lupercalia would be incomplete without recourse to Vedic religion.

More than a century has now passed since Croatian artist Ivan Metrovi said: I and my people, being considered barbarians and an inferior race, feel a certain distrust of European culture The sentiment that he expressed has changed in the light of the disintegration of European empires and the fall of the Iron Curtain. But it has not entirely disappeared. It will be clear to anyone familiar with the most populous European languages that the words Slav and slave are etymologically and ideologically related. Eastern Europe is one in a series of Western imperialist constructs with ever-shifting borders and no end in sight.

My rejection of nationalistic ideologies also stems from the disintegration of communism in this part of the world. I was born in Yugoslavia, a chimerical entity that fell apart in bloody war when I was four years old. My first memories are filled with news of battles, military parades, and war songs. My first childhood friends were refugees. I say this because my outsider status should be evident to anyone reading this book. Classics in the so-called Western world still bears so many traits of an elite discipline, though there is hope in the growing acceptance of diversity.

My aversion to imperialist projects is also a consequence of having lived in a beautiful country, Croatia, where all the operations of state have combined the inheritance of several imperialist bureaucracies with that of communist apparatchiks. I have despised fascism and its nationalist descendants because their totalitarian tendencies are quick to dismiss any perspective but their own, perspectives which are invariably heteronormative. For what it is worth, I do not believe that I project my queerness onto a study of Roman and Vedic priests, warriors, and young men and women, one that seems to point to an ancient system in the murky waters of Indo-European prehistory. However, when it comes to wolves, my name itself betrays me: I was born Vukovi (Wolfson) and this accidental signifier of Slavonic affiliation (in fact one of the most frequent Croatian surnames) has played a small part in my fascination with these wild animals, though I cannot vouch for shedding my skin to fight vampires at night.

The wolf occupies a central position in the foundation myth of Rome, but few scholars have taken the animal seriously. Most have confined themselves to the study of the wolf as a symbol. This probably has to do with the fact that we are raised with stories of the Big Bad Wolf. The majority of humans choose to believe that wolves habitually kill humans and cattle. In fact, statistics show that more humans die from encounters with cows, vending machines, and even toothpicks than from wolf attacks. Human hatred of wolves partly stems from the fact that they are similar to us in many respects. Wolves are powerful social animals that fascinated early cultures on the move; the Roman complex of the Lupercalia carries memories of a time in which nature and culture were not strictly separated, and when men identified with wolves in rites of passage.

This book takes the Lupercalia on a journey from prehistory in the Eurasian steppes to the furious condemnations of a Pope in the Rome of the late fifth century AD. A time span so large touches on many different fields of expertise in which I am not an expert. I tried to consult and engage with the relevant bibliography, and I hope that specialists in various areas will excuse my inevitable omissions. The term Indo-European has always been fraught with political baggage, most famously in its approximation with the construct of Aryan or Nordic race. In the face of such history, you would have to be very self-righteous, and, frankly, pretty un-self-aware, to think your own political commitments are so transparently and comprehensively beyond reproach that no future will find you lacking in some significant respect.

Acknowledgements

I incurred many debts in writing this book and it is no overstatement to say that it would not have been completed without the support of so many friends and colleagues. My supervisor Stephen Heyworth guided my thesis with a steady hand and provided essential aid throughout the process. Since that time many stimulating conversations with him helped me clarify my ideas and structure the book. My co-supervisors Gavin Flood and Anna Clark helped with my comparative research and Roman history, respectively. Milinda Banerjee encouraged me to work on the topic long after many others declared it unworthy of a book. He has been a constant wellspring of ideas and I would be nowhere without our lively discussions. My friend Maria Mariola Glavan read the whole manuscript of the book with a meticulous eye for errors and saved me from my Illyrian English. She and Helena Philipps-Robins have been wonderful collocutors and provided invaluable support. Elizabeth Tucker taught me Vedic Sanskrit and helped with Vedic terminology and mythology in the book. The late Daniel Neas Hraste opended my eyes to the beauty of Roman religion as an undergraduate at the University of Zadar. Enrico Prodi and Stefania Peterlini wrote to Italian museums and institutions on my behalf to obtain permission for the figures included here. David Sick, Aleksandr Koptev, and Francis Brassard kindly read several chapters and provided useful feedback during the final stage of writing. Lovro Luli helped with the referencing software. The series editors, Milinda Banerjee, Julia C. Schneider and Simon Yarrow carefully read the text and provided valuable suggestions. Many stimulating conversations with John and Caitlin Matthews inspired my comparative appreciation of ancient mythologies. My family have been a wellspring of support in all times, and I would especially like to thank my mother, Kata Vukovi, for her religious devotion, my late father Ante Vukovi, my brothers Slavimir, Zvonimir, and Zorislav and their partners, Branka and Iva, and especially Sanja Cicvara, who has always managed to find more questions than I am able to answer. I hope this book will open more questions for her and others.