Contents

Guide

Julia Matveev

Ludwig Strauss: An Approach to His Bilingual Parallel Poems

Conditio Judaica

Studien und Quellen zur deutsch-jdischen

Literatur- und Kulturgeschichte

Herausgegeben von

Hans Otto Horch

In Verbindung mit Alfred Bodenheimer,

Mark H. Gelber und Jakob Hessing

Band 93

ISBN 978-3-11-058750-0

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-059076-0

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-058763-0

ISSN 0941-5866

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018947223

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

www.degruyter.com

To my husband Valeri and my daughters Anna and Dina

Praised be your name, no one.

For your sake

we shall flower.

Towards

you.

Psalm, Paul Celan

(Translated by Michael Hamburger)

Acknowledgments

Parts of this book were presented on various occasions as papers at conferences and workshops or as invited lectures. I am deeply grateful to my colleagues and friends, Professor Bettina Bannasch, the Department of Newer German Literature, Institute for German Studies, Faculty of Philology and History at the University of Augsburg, and Professor Dorothee Gelhard, the Graduate School for East and South Eastern Europe Studies, the University of Regensburg, who supported this project from the very beginning. They gave me the chance to discuss and improve my ideas by inviting me to teach seminars at their universities. My research benefited greatly from being able to share ideas with the students, who inspired me with their enquiring minds and at times difficult and provocative questions. I am particularly indebted to Emanuel Tatu from the University of Regensburg as well as Karin Binder () and Gerhild Rochus from the University of Augsburg for providing reference material, articles and autobiographical books, which helped me in my research. This book would probably not have come to fruition without the support of Professor Gelhard and Professor Bannasch, to whom I am indebted for their unfailing help, generosity and encouragement. The dialogues I had with Professor Bannasch, with whom I worked on the project Literature of the Jeckes between 2012 and 2014, provided a source of ongoing inspiration. I also profited greatly from stimulating discussions with Professor Gelhard, whose challenging comments and questions pushed me to delve deeper and think more creatively.

I am grateful for the encouragement I received from Professor Itta Shedletzky of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and wish to thank her for listening to my ideas, as well as for her advices at the early stages of this project, and, most importantly, for her friendship. I also wish to thank Professor Paul Mendes-Flohr, Professor Emeritus at the Department of Jewish Thought of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Professor of Modern Jewish Thought at the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, who was a model of intellectual integrity. I am enormously grateful to him for his moral support during the process of writing, as well as for the endless care and concern he showed me.

I wish to thank the Joseph Carlebach Institute for Research into Religious Jewish Thought in Germany, Bar-Ilan University, in particular its director, Dr. George Kohler, for supporting my work.

Further thanks go to Bella Strauss and Tuvia Rbner for their generous support, for the information they shared with me about Ludwig Strauss, and for giving me permission to publish unpublished archival material (the draft of the Hebrew poem To the Bay written by Strauss in 1934, fragments from the Hebrew variant of his Hymn to Asia, and the distich, written in Hebrew on the inside cover of his second poetic notebook) from the Ludwig Strauss archive at the Department of Manuscripts and Archives at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem.

I also extend my thanks to the National Library of Israel and to all the librarians and archivists at the Department of Manuscripts at the National Library, especially Dr. Stefan Litt for his cooperation and help.

I would like to thank Paul Maurer, librarian at the National Library of Israel and the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, for providing a copy of the English translation of Strausss poem In the discreet Splendor.

I also thank Rabbi Binyamin Zimmerman and Rabbi Elchanan Samet for permission to quote from their lectures and the Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash of Yeshivat Har Etzion, where these lectures were posted online.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to Susan Kennedy for her kind assistance throughout the final preparation of this book, for helping with the editing, and for her useful suggestions.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my family, my husband Valeri and my daughters Anna and Dina, for their patience and love, and for supporting me spiritually throughout the writing of this book. I dedicate this book to them.

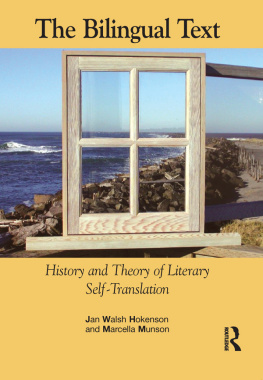

1Introduction

As the title implies, this book is an interpretative commentary on bilingual parallel poems by (Arie) Ludwig Strauss (also: Strau) (Aachen 1892 Jerusalem 1953) which exist in two variants, a Hebrew and a German version, one of which is the original composition and the other a self-translated verse constructed against the background of the former. These poems were created between 1934 and 1952, when Strauss began to write in Modern Hebrew (Ivrit), the national tongue which he painstakingly acquired by means of formal study, while at the same time continuing to compose poetry in German, his mother tongue, which had previously been the sole medium of his poetic expression. As Jrgen Nieraad points out, among the German-speaking Jewish authors who immigrated to what was then Mandatory Palestine (now Israel) in the 1930s (during the fifth wave of Jewish mass immigration known as the Fifth Aliyah, 19331939), as refugees fleeing persecution from the German National Socialist regime or as Zionists committed to creating an authentic Jewish life and a Modern Hebrew culture in Eretz Israel, or for both reasons, Strauss was the only poet (or, to be exact, one of the very few). Both languages, he insisted, were engaged in the process of self-translation, yet the poem, suddenly and unexpectedly, found its expression not in his native German but in Hebrew the language he had begun to communicate in upon his arrival to Palestine when in his forties. He was surprised at his ability to use that language as his literary tongue even if that had been his goal from the outset of his literary career some two decades earlier. An admirer of Ahad HaAm (18561927) and a proponent of cultural Zionism, Strauss as early as 1912 pondered the possibility of starting to write in Hebrew, as Paul Mendes-Flohr points out in his book German Jews: A Dual Identity (1999) when he cites Strausss statement, published under his literary pseudonym Franz Quentin in the Munich journal The Guardian of Art ( Der Kunstwart ):