Landmarks

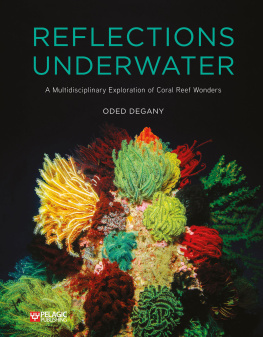

Reflections

Underwater

Published in 2023 by

Pelagic Publishing

2022 Wenlock Road

London N1 7GU, UK

www.pelagicpublishing.com

Reflections Underwater

A Multidisciplinary Exploration of Coral Reef Wonders

Editor: Shoshana Brickman

Scientific editor: Dr. Tom Shlesinger

Photographs: Oded Degany

Illustrations: Anath Abensour

Book design: Inbal Reuven

Additional credits are included on the bibliography and figure credits pages.

Copyright 2023, Oded Degany

The right of Oded Degany to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher and the author, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles.

https://doi.org/10.53061/PJYM7953

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78427-413-9 Hardback

ISBN 978-1-78427-414-6 ePub

ISBN 978-1-78427-415-3 PDF

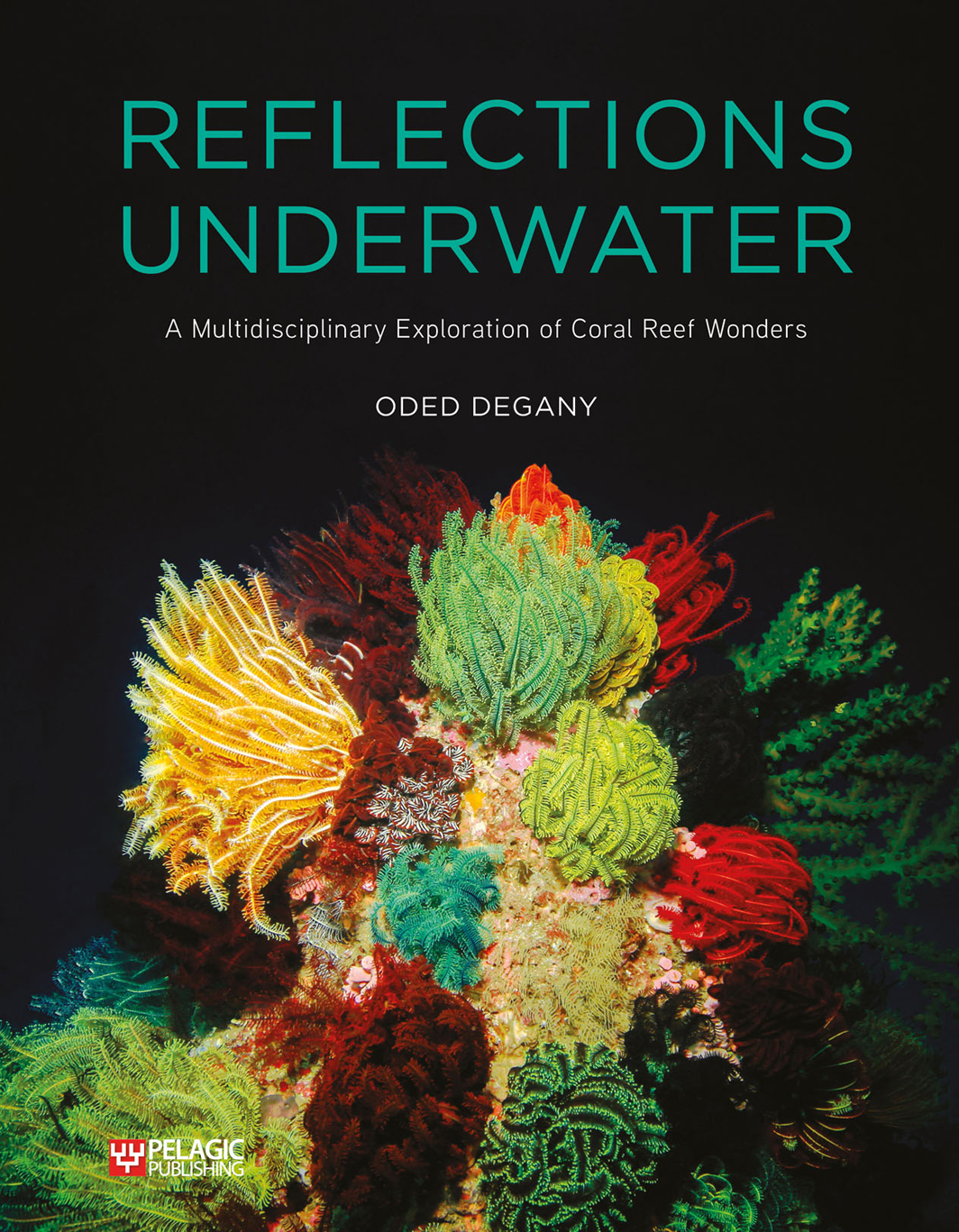

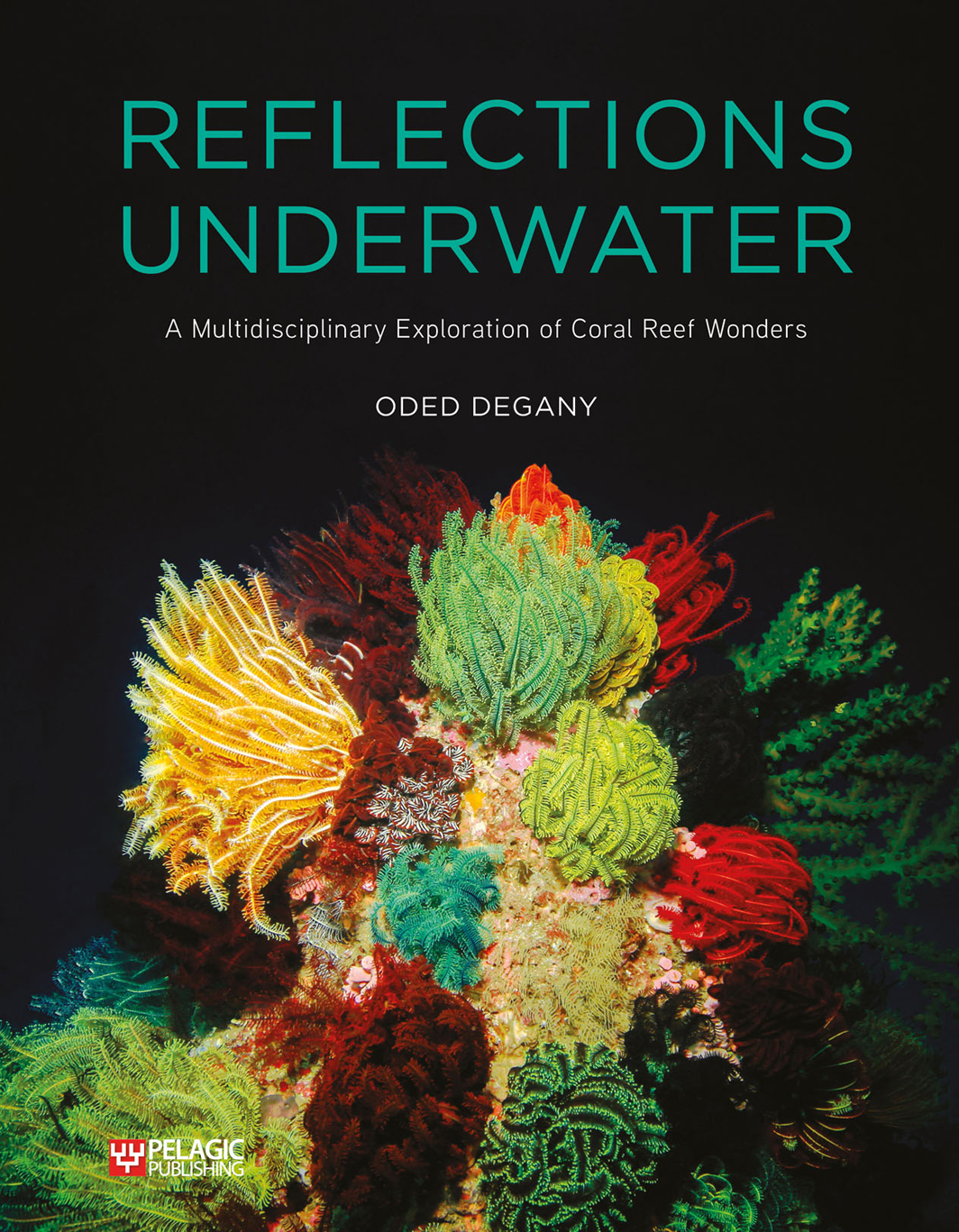

Front cover: Pinnacle of Crinoids (sea lilies). Puerto Galera, Philippines.

Spine: School of anthias. Verde Island, Philippines.

Back cover: Spotted-ribbontail rays eye. Eilat, Israel; Freckled (scarlet) frogfish. Lembeh Strait, Indonesia.

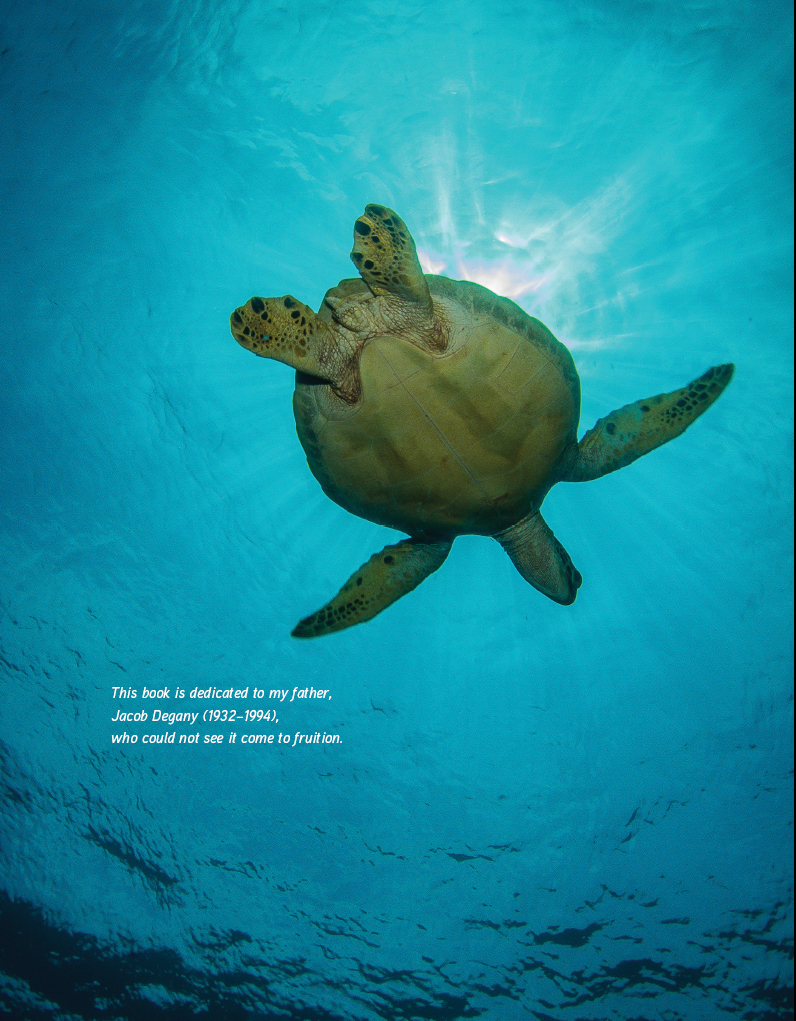

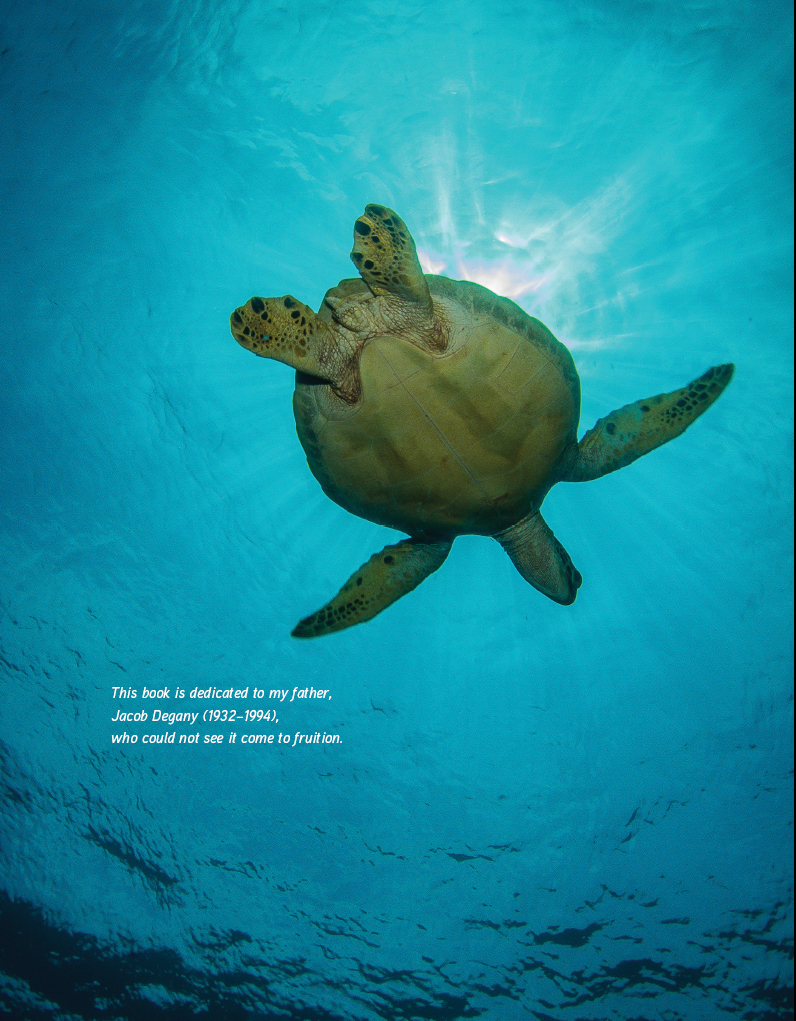

Sea turtle. Bunaken, Indonesia.

The sea is everything. It covers seven tenths of the terrestrial globe. Its breath is pure and healthy. It is an immense desert, where man is never lonely, for he feels life stirring on all sides. The sea is only the embodiment of a supernatural and wonderful existence. It is nothing but love and emotion; it is the Living Infinite.

Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea: A World Tour Underwater, 1872

Contents

Foraging lionfish. Eilat, Israel.

Shuzan held out his short staff and said: If you call this a short staff, you oppose its reality. If you do not call it a short staff, you ignore the fact. Now what do you wish to call this?

Zen Koan

By Professor David Fortus

The Chief Justice Bora Laskin Professorial Chair

of Science Teaching, Weizmann Institute of Science

There is something on my table. It is almost symmetrical around a vertical axis. It is hard, but not brittle. It is made of organic materials. Once it was home to many organisms, now to fewer. It is wet on the inside but dry outside. It does not conduct electricity. It has sentimental value to me. What is it? Do these descriptions of the objects properties bring it to life or do they actually deaden it? Can knowledge of these properties replace the sense of appreciation that may come with experiencing the object, by holding it, seeing it, using it, smelling and perhaps tasting it? Do they limit or enhance ones experience with the object?

Whenever we inspect any object or phenomenon, we see different things depending on the perspective we adopt. A physicist sees in a leaf countless energy transformations, a chemist the synthesis of sugars, the evolutionary biologist an adaptation to an environment, an indigenous shaman the source of a substance to relieve pain, and so on So is a leaf just a leaf, or is it much more? Can we really know what a leaf is and fully grasp its reality, or by simply calling it a leaf are we actually constraining it and limiting our ability to fully appreciate it?

Epistemology, which deals with the nature and the justification for our perceptions and conceptions of the world, is central to philosophical discourse. Emmanuel Kant was the first to challenge the longstanding historical pretension that the world could be understood in a completely objective manner, claiming that our conceptions of the external world were not accurate reflections of objective external reality. Instead, according to Kant, the human mind acts as an organizer, constructing our conception of reality based on a priori concepts and our senses inputs and not merely on experience. A priori concepts and sensation, Kant believed, led to conception, and different senses would lead to different conceptions. Since our senses are uniquely human, we have a unique and anthropocentric conception of nature. We simply cannot view the world other than the way we do. This anthropocentrism may underlie our ethical approach to nature, leading to the belief that humans stand in the center of the universe and are superior to nature, a worldview that is criticized several times in Deganys book. However, Kants theory has itself been challenged; the fact that Degany is human but argues against anthropocentrism can be seen as evidence that not all our conceptions may be derived from our senses.

This remarkable book clearly adopts the perspective that knowledge enhances experience, but cannot replace it. Reading this will not make diving at coral reefs unnecessary; it will embellish the experience. If you dive regularly at coral reefs, this book will show you new ways of seeing the reef, changing your experience of it. But rather than having to read one book about reefs by a physicist, another one by a mathematician, another one by a marine biologist, another one by an anthropologist, and yet another one by a philosopher, Degany has done something unique, he has combined all these perspectives in a single book. He has succeeded in demonstrating that, as far as the reef is concerned, everything is connected.

But more than that, Degany continually draws parallels between the reef and the human condition, so you will learn a lot about people, not just about polyps and octopuses and other marine creatures. You will learn about reproduction strategies in the reef and have these compared to gender and sexuality in humans. You will learn about the power of numbers, not only in fish schools, but with people. You will learn about shamanism, zombies, the dispute between Newton and Goethe about color theory, and much more. In the end, this book provides a very humanistic perspective on the reef: by learning about the reef, we are learning about ourselves.

In the end though, no matter how much we learn, we are limited in our ability to conceive of the reef in its totality, just as I am limited in my ability to understand all the various aspects that make the object on my desk what it is. In spite of the incredible eruditeness underlying this book, it is clear to Degany that he is only scratching the surface, that some things cannot be fully explained by reductionist approaches like science. In this sense, this book is modest, about our ability to understand nature and about humanitys place in nature. Hopefully, this will be another insight that readers will take away with them: We are blind elephants in an intricately organized china store. Even when our eyes are opened, we can still barely see. Let us be aware of our limitedness and proceed cautiously, showing respect for and awe of Mother Nature.

This book is extraordinary, original, beautiful, and fascinating. Degany has an incredible mind. I have met many brilliant people, but only extremely few have interests so broad, are knowledgeable about such a wide range of disciplines, and delve into the tiniest details underlying a topic but at the same time are able to see the big picture. This book justifies Descartes, who thought that The reading of all good books is like a conversation with the finest minds. At a time when society encourages, promotes and often dictates specialization at the expense of broadness, when too many scientists know everything about almost nothing but almost nothing about everything, it is refreshing to see that it is still possible to be both broad and deep. It is also refreshing to see that there are fundamental questions that cannot be addressed without using multidisciplinary perspectives.