Contents

Guide

Page List

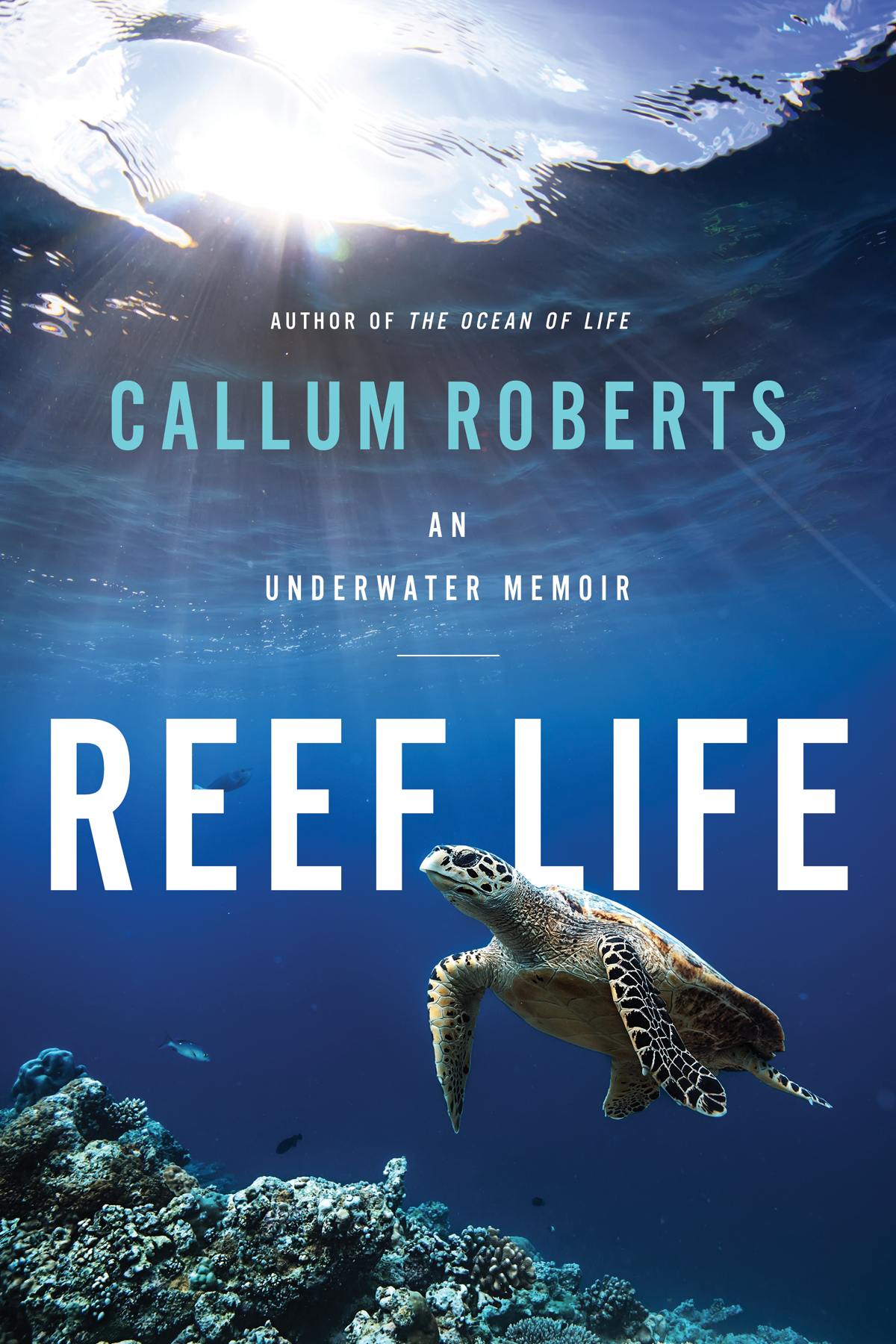

REEF LIFE

AN UNDERWATER MEMOIR

CALLUM ROBERTS

with photographs by

ALEX MUSTARD

For Felicity Flic Wishart (19652015), who campaigned tirelessly for coral reef protection so that wildlife could thrive and future generations might still revel in their wonder.

And with deep gratitude to Alex Mustard MBE for his wonderful photos, which bring coral reefs to life within these pages.

Contents

LEAPING INTO THE SEA, we plunge mid-stream into a fast current. Despite brilliant sunshine above, underneath the water is evening blue, darkening to twilight beyond the play of sunbeams. We dive immediately in the direction we expect the coral reef to be; even a momentary pause risks hopeless disorientation in this formless space. I fly downward into what seems like eternity, wondering as the water deepens whether there is anything there. But the blue soon becomes shadowed and outlines of fish appear, then a beetling cliff, its face pocked with caves, sea fans and flourishes of coral.

From our eagles-eye view, this reef is an elongated hill, its rounded summit peaking fifteen metres below the surface. We level off beside the cliff twenty-five metres down, battling the current towards a promontory at the northern edge, keeping tight in to ride the boundary layer where corals slow the flow. The corals here are fantastically varied, with pillows, branching shrubs, filigreed tables, towering trunks like oak limbs, or delicate lace frills. Around them a commotion of fish renders the current visible as they stream past or hold position, tails beating like flags in a gale. Nearing the point, I am kicking furiously but can only edge forwards. Finding ourselves at last at the foot of the escarpment, faces full into the blow, we drop our reef hooks and ride the stream at anchor, fixed to the bottom by a thrumming umbilical of parachute cord.

Here in the eye of the current, fish mass in shoals, milling, swooping and turning, sheering away and streaming back, like winter wader flocks above an estuary. The water is thick with fusiliers nodding plankton from the rich draft pouring from the open sea. They are similar in size to herring and share their sleek lines, but instead of cool monotones, fusiliers are coloured with bold strokes of tropical blue, canary yellow and orange, like nursery school paintings. Greater fish glide past further off, casting predatory looks over the shoals. Half a dozen giant trevallies at least a metre long scud past with chopping tail beats. Their steep heads and scowling mouths lend them dangerous purposefulness. The bodies are deep and muscular, the flanks silver-plated, and from shoulders to tail the arc of their backs is the blue of tempered steel. Further down, a tunny patrols the footing of the reef, streamlined like a torpedo, throwing flashes of sunshine from its metallic belly. Its watching for a fish off its guard, perhaps one that has strayed too far from the safety of the coral following a crumb trail of incoming plankton.

Then in the misted emptiness beyond the reef, a white crescent moves centre stage attached to a bigger shadow: a grey reef shark. The crescent edges the curve of a dorsal fin, the body is ghostly, half real, half imagined. As my eyes adjust, other crescent moons cut and weave through the dark water, rounded backs and angular fins briefly visible as they catch sunbeams. Its hard to tell how many there are. The current shakes the mask on my face and swings me side to side on my reef hook anchor. But the sharks ride the current slowly, purposeful and effortless, bending it to their will with movements too subtle to see. Hanging at the edge of visibility, the big fish seem to taunt, tempting us to follow them away from the reef. But we are rooted here by the press of water. The source of their freedom holds us. The currents they command will sweep us away the moment we unhitch, which we do now, our tanks already half empty.

Free to drift, the reef rushes past, rewinding the first part of the dive and then sweeping us into new terrain. Looking up the dark cliff face, I see silhouetted sea fans spread like netted fingers and branching corals that look like winter trees. But the leaves of these trees are still there, unattached and swirling about the branch tips. At least that is how the thousands of tiny fish appear from below, dark ovals against the light. As we approach the downstream tail of the reef, the slope shallows and the bottom is bathed in light. Blood-red encrusting sponges splash the seabed, wrapping coral stems like canker. Tiny fish shimmer above dense beds of branching coral, noses to the current, tails beating feverishly to hold their positions. Their bodies form ever-changing clouds of jewel green, olive, and the orange of autumn leaves. Driven by the current, we swing up slope to shelter in the lee of giant coral hummocks that look like the remains of a rockfall.

A mantis shrimp peers from beneath the edge of an upturned clamshell. Its carapace is mottled green, edged with a thin red line like the piping on an iced cake. Its eyes are frosted glass balls on blue stalks, marked with a horizontal line like the slot of a helmet visor. Their science fiction appearance accords with an almost supernatural power, the ability to see polarised light. The shrimps can peer further and more clearly in the particle-laden water just above the seabed.

The upper surfaces of the coral blocks are a continuous carpet of green tentacles that shivers in the current like wind through summer hay. The current lifts the edges of these anemones to show purple and carmine underskirts. Above the tentacle sward, the water is thick with fish, their bodies bobbing and dipping in a fluid dance. Black damselfish snowflaked with titanium spots mingle with fish whose mocha bodies, scored with three white bars, are outlined by a poster-yellow fringe of rounded fins. Their faces are blunt, with big dark eyes above thick-lipped glowering mouths. But above all there are hundreds of orange anemonefish flocking above the tentacles, their faces outlined behind the eye with a single white bar, their underbellies black streaked, their tails sunshine yellow. The water is filled with the crackling chatter of grunted conversation as fish see off rivals and keep allies close.

There are fishes of all sizes here, golden as pennies, spotted like dominoes or showy chrysanthemum flowers. The smallest dive among the tentacles at my approach, turning to peer back like children hiding behind curtains. The big fish launch bold sallies and warn me off with shouted staccato grunts. There is a buzzing energy that feels like an angry mob, but in fact there is a well-honed hierarchy, albeit one constantly tested. The largest fish are matriarch females that do all the breeding, laying their eggs under the skirted edges of the anemones. Normally, there would be just one such female in a group, but the anemones are so densely packed that dozens share the space, each with her own attendant males. When a matriarch dies, the largest of her males changes sex to replace her. From the abundance of miniature fish here, it looks like a crche, but probably none are the offspring of resident fish. They arrived as larvae that had drifted from far away, hatched from the eggs of others.