Contents

Page List

Guide

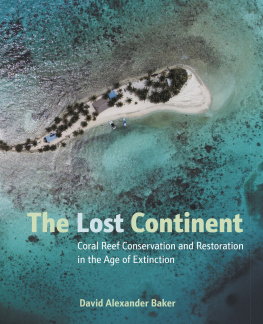

Cover

CORAL

REEFS

A NATURAL HISTORY

Charles Sheppard

Consultant Editor

Russell Kelley

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

THE CORAL ANIMAL

CHAPTER 2

DIFFERENT KINDS OF REEFS

CHAPTER 3

HOW A CORAL REEF WORKS

CHAPTER 4

LOCAL AND REGIONAL DISTURBANCES TO REEFS

CHAPTER 5

CLIMATE CHANGE AND REEFS

CHAPTER 6

PEOPLE AND REEFS

FOREWORD

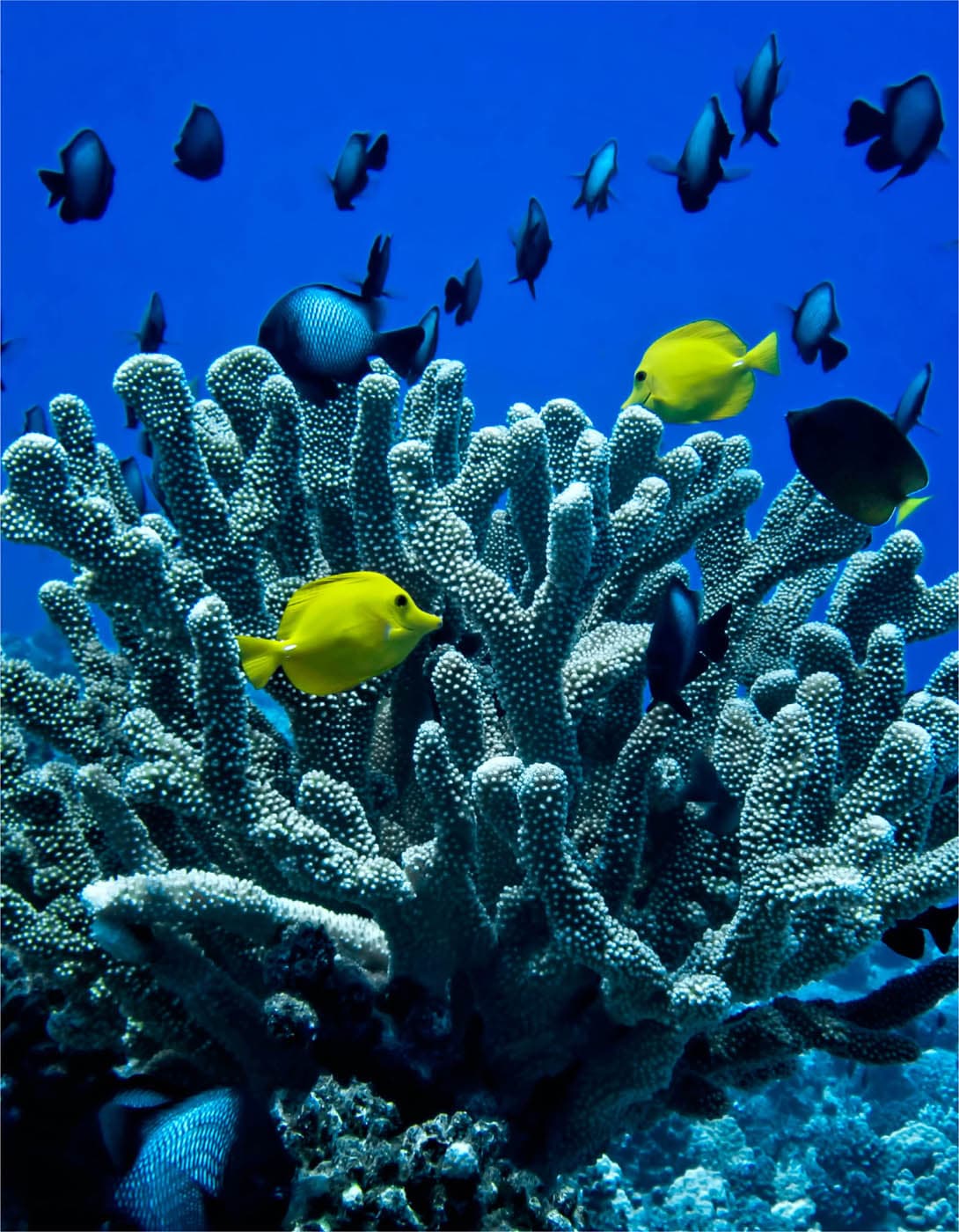

Imagine swimming in a warm, tropical sea. Through your face mask you peer down into an infinite azure abyss. All you can see are shafts of light plunging into the depths like lightsabers, and iridescent, sapphire-like flashes reflecting from invisible plankton somewhere below. Now you hear something between the lazy splashes of the torpid sea. A non-stop crackling hiss rises and falls like someone tuning a distant radio station. You kick your fins and turn 180 degrees and a vertical reef wall looms, draped in a wriggling tapestry of color and movement. Fish teem around hundreds of other kinds of reef creatures. You swim closer and gawp at the hallucinogenic patterns while the entire coral reef carnival carries on without a care for an alien visitor as clumsy as yourself.

For me, there is nothing as ineffably beautiful as a coral reef on a calm, sunny daysuch scenes sear vivid memories that last a lifetime. Remarkably, the story of reefstheir origins, adaptations, and achievements in the great pantheon of evolution and Natureis equally breathtaking.

From the study of modern reefs, we know corals are not just beautiful biological baubles, but an innovative force in Nature. Corals have solved the problem of how to create something from nothing in the middle of empty, nutrient-poor oceans using an ecology based on symbiosis and collaboration. And not just a modest something, but the richest marine ecosystem on Earth.

The coral reef innovation derives from an extraordinary advent in biologythe ability for a plant to live inside an animal, the best known example being the algae cells laced through the tissues of every reef-building coral polyp.

Somewhere in the mists of geological time, shallow-water corals became infected with plant cells that not only survived but thrived within the coral animal. These tiny plant cells did what plants do: photosynthesise. Using sunlight, excess CO2, and animal waste products, they flourished inside their host. In return the plant cells released sugars and the humble coral polyp suddenly had two engines for growtha carnivore by night and a solar farm by day. Now corals had energy to burn, energy to build!

Their larvae dispersed on ocean currents to settle on the edges of sterile volcanoes where, with nothing but sunlight and microscopic planktonic meals, they combined their construction prowess with another great evolutionary achievementcloning. In this way the arrival of a single coral larva, transforming into a polyp, could build great coral colonies. I like to think of them as colonial castles conjured from nothing in the middle of empty oceans.

On coral reefs recycling is a way of life, as is finding a home on, or inside, another species. Over many millions of years coral reefs have attracted thousands of species to come along for the ride, weaving an evolutionary fabric so organically intricate it inspires, and deserves, the term living art.

This book explores the natural history of reefs in a human context. Written plainly and richly illustrated, it is a guide to the good, the bad, and the ugly of the coral reef story. Around the world Nature is in retreat and so it is with reefs. In the tropical world around 500 million people depend on reefs for shelter, protein, and employment. Yet in many regions reef decline is accelerating due to the impacts of growing populations of people without options.

Even more pressing is the threat of climate change and the ocean warming it causes. Underwater heatwaves are triggering mass coral bleaching, a disease (described on ) that attacks the evolutionary bond between coral and algae, the very engine of the ecosystems existence.

Coral Reefs; A Natural History is a portrait of the wonders and dilemmas facing the richest of marine realms. If we want our children to see Natures great gifts, and if millions of people are to avoid displacement and hardship, then it is time for humanity to take our collective foot off the carbon emissions accelerator.

Russell Kelley

Townsville, Queensland, Australia

INTRODUCTION

Coral reefs mean different things to different people. To a sea captain they are potentially hazardous, often poorly marked on the chart, and always lying just beneath the surface of the water. To people living in the tropics beside a reef, or on a small island perched on one, they provide both a home and food. To many divers and snorkelers who visit tropical coasts they are a kaleidoscopic wonderland of colorful fish that circle and dart above the strangest of living structures, and these tourists bring significant revenue and foreign earnings to such regions. The scientist sees something different again, a place of huge diversity in a relatively small space, of apparently chaotic pattern and movement, something to try to make sense of. A reef is all of these things and more.

Coral reefs occupy only about one percent of the Earths surface but they contain a high abundance of marine species, and they concentrate huge densities of it too, like an oasis. Not only this, but they also construct the reef itself. A reef is made by corals and other organisms as they extract limestone from the seawater to deposit as solid rock to make their own skeletons. They have been doing this for millennia so that now some reefs are a couple of kilometers thick in parts of the Earth that have been slowly subsiding over the ages, such as in the atolls scattered across tropical parts of the Indian and Pacific oceans. The parts of the reef that are now living form only a veneer on the top. Yet that small quantity has built the structure that supports all the rest, from the thousands of species of simple animals to the swarms of fish above, and to several entire oceanic nations.

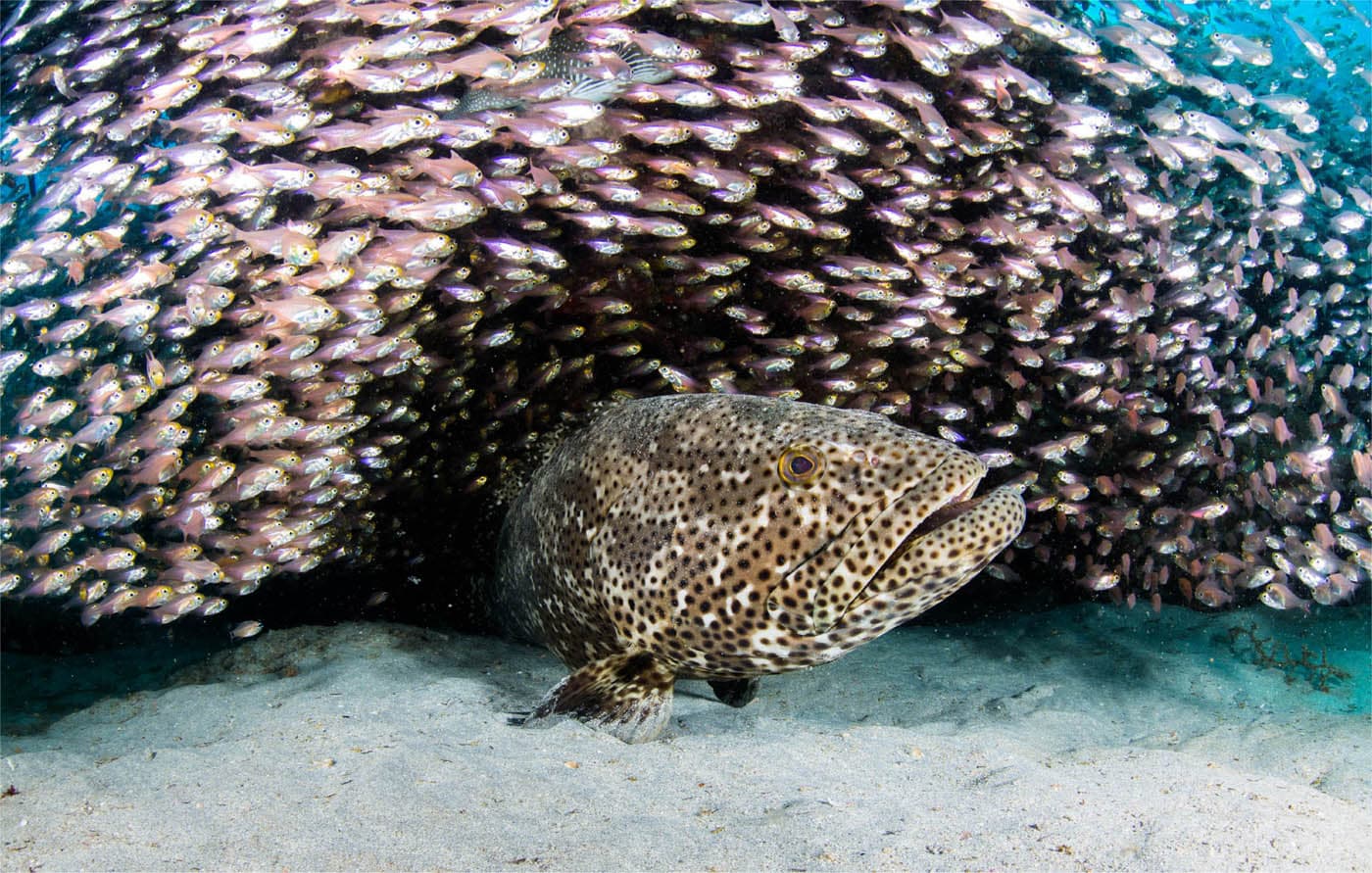

A grouper on a Western Australian reef. Grouper are ambush predators and commonly hide in caves, though here the cave is concealed by the shoal of small, silvery fish.

Few of us realize that around half a billion to a billion people are now wholly or largely dependent on coral reefs, because they live on them or are dependent on the protein that they produce, or perhaps because they provide sheltered waters for a mainland settlement. That number does not include many millions more who use them for recreation.