PART I.

Reef Futures

PART II.

What Keeps a Reef Together

PART III.

Florida

PART IV.

Sulawesi

PART V.

Bali

PART VI.

Dominican Republic

PART VII.

Washington, D.C.

PART VIII.

Australia, from Afar

1

Fairy Land of Fact

It was love at first sight, for my part anyway. Im pretty confident the corals felt nothing more than the waft of a current rolling off my flapping fins as I struggled to control my movements. But from the moment I dipped my eyes beneath the surface of the balmy Red Sea and kicked a few meters out to the reef, I was smitten. I had entered a world in which the sea gods and goddesses had conspired to mastermind a magnificent playground and then outfitted it in extraordinary decor. Awash in color and texture, the reef was beyond Baroque, more complex than Gothic. It was floral, it was animal, and it was mineral too. Each delicate petal and tendril was a revelation; each filigree and lattice an astonishment. It wasnt just my ineptness with a snorkel that literally choked me up. I felt emotional, overwhelmed by the simple recognition that this coral reef existed on the same planet as me.

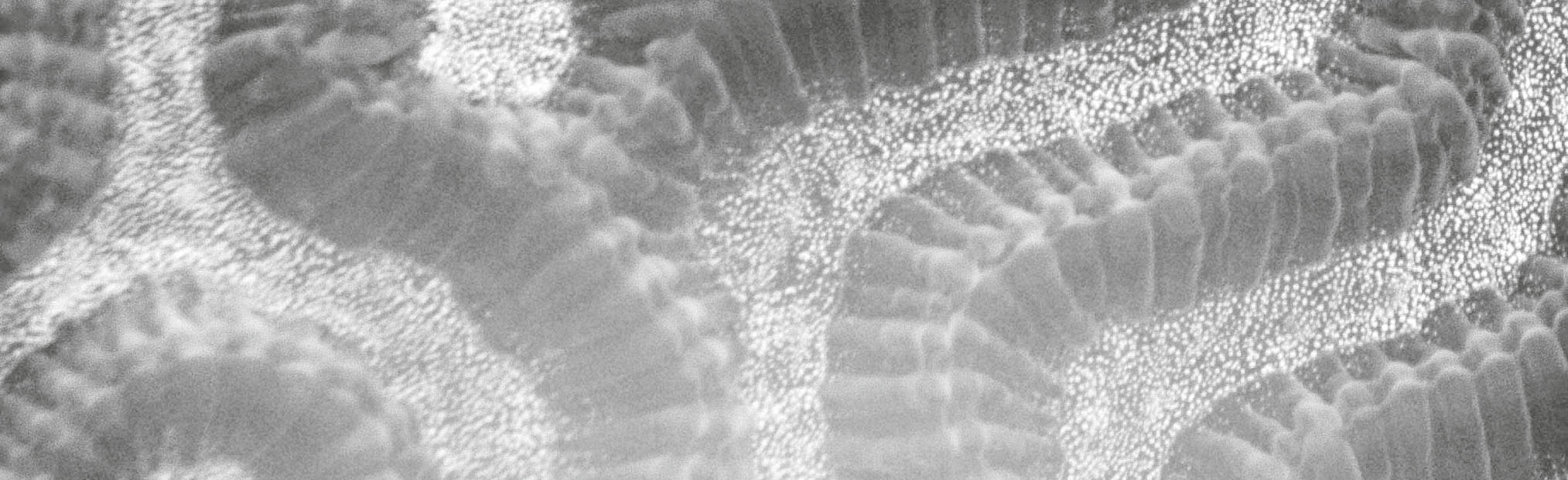

What really made the reef so resplendent was that there was no sea divinity behind its magnificence. It was, as William Saville-Kent, the Great Barrier Reefs first Western biographer, wrote in 1893, a fairy land of fact. The fairyland was the accumulated work over the eons of hundreds of thousands of tiny animalsmost no bigger than the tip of a penciland the symbiotic algae that lived tattooed in their tissue. These creatures had none of the organs that we recognize as animal-like, no limbs or eyes or even brains with which to concoct this symphony of splendor. And yet, they had extraordinary capabilities. They were architects who designed the intricate structures of the reef. They were manufacturers who created the rock scaffolding of their homes. They were chemists who made their own protective sunscreen and complicated venoms. They were entrepreneurs who traded in the currency of nitrogen and carbon. They were soldiers who defended their territory from encroaching parties by firing poison-laden darts with unparalleled speed. They were hunters who used those very same extraordinary weapons to sustain themselves.

What was even more inconceivable was that these tiny beings were so much more than just their individual powers. And it was for the collective that my admiration of corals blossomed into true love. They were generous, sharing their nutrition with their neighbors through stomachs that were physically connected together. They were hospitable, building caves and dens for fish and crabs and octopuses and sponges. They were sensual. In the light of the moon, they spawned as one, releasing eggs and sperm upward in a deluge of synchronized hope for the future.

In the years following that first amorous dive on the reef, I changed my life in very significant ways, as one does for a true love. As often happens with passion, it didnt always go smoothly. But after many missteps, I did go to graduate school to study marine biology. Once there, I signed up for every chance I could to dive on other reefs: the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and on the reefs surrounding Bora Bora, Jamaica, Maui, and the tip of Baja California. When I tucked my head underwater, the rush of love for the coral reef would always wash over me. Again and again, I was enthralled and entranced by the corals, by their creativity and synergy, by their beauty and complexity.

Until I wasnt.

More than a decade ago, I fell off the academic path and slipped into a career as a freelance science writer mostly working on textbooks, although I occasionally wrote for magazines and websites. My grandmother, who was in her midnineties, decided to throw a big party for herself because, as she wisely recognized, you cant take it with you. She invited our extended family to join her on a Caribbean cruise. While I knew this voyage would be different from sailing on a research vessel, I was eager to see the vast horizon again and for the chance to dive beneath the turquoise waters in the Bahamas and swim around the coral gardens. This cruise company owned an entire island there and we were promised a day of snorkeling.

Aside from being at sea, the cruise was, as expected, strikingly different from life on a research vessel. On scientific cruises, work continued around the clock, which usually meant no more than a few hours of sleep at a time and a constant feeling of grogginess. Here, the ships staff built a schedule to maximize our enjoyment of various shore activities. We sailed at night, rocked to sleep by the gentle roll of the waves, and awoke to a fresh new vista ripe for adventure each morning. The day we docked on the private island, I pulled back the blinds to the sight of a stunning double rainbow that ended at the beach. How they managed that feat, I had no idea.