SAGE Publications Ltd

1 Olivers Yard

55 City Road

London EC1Y 1SP

SAGE Publications Inc.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area

Mathura Road

New Delhi 110 044

SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd

3 Church Street

#10-04 Samsung Hub

Singapore 049483

Paul Atkinson 2020

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Printed on paper from sustainable resources

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941659

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-5264-6341-8

ISBN 978-1-5264-6342-5 (pbk)

Editor: Alysha Owen

Editorial Assistant: Lauren Jacobs

Production Editor: Jessica Masih

Copyeditor: Rosemary Campbell

Proofreader: Neville Hankins

Indexer: David Rudeforth

Marketing Manager: Susheel Gokarakonda

Cover Design: Shaun Mercier

Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd, Chennai, India

Printed in the UK

At SAGE we take sustainability seriously. Most of our products are printed in the UK using responsibly sourced papers and boards. When we print overseas we ensure sustainable papers are used as measured by the PREPS grading system. We undertake an annual audit to monitor our sustainability.

About the Author

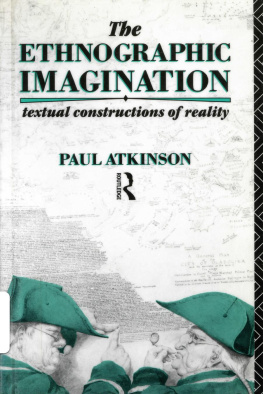

Paul Atkinsonis Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Cardiff University. Recent publications include

For Ethnography (Sage 2014) and

Thinking Ethnographically (Sage 2017). The fourth book in his quartet will be

Crafting Ethnography, also for Sage. The fourth edition of Hammersley and Atkinsons

Ethnography: Principles in Practice was published by Routledge in 2019. He is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and of the Learned Society of Wales.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to a great many colleagues, students and friends, especially to members of the Cardiff Ethnography Group. Over many years they have been constant sources of inspiration and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Emilie Whitaker, who has in recent years challenged me to think afresh about ethnography, creativity and writing. Martyn Hammersley has been a staunch friend and co-author; we disagree about points of detail, but encourage one another about the bigger pictures. My greatest debt is to Sara Delamont, whose companionship and advice have been invaluable for nearly 50 years. She is my best friend and my best critic. I am especially thankful for Mila Steele, my long-term publisher at Sage. Her enthusiasm and her company are always a delight. The task of looking after me has now fallen to Alysha Owen, and I am grateful to her for her support and encouragement.

Introduction Writing Matters

While this book stands on its own, it is also the third part of a quartet (to be completed by Crafting Ethnography). In the first, For Ethnography (2014), I laid out a manifesto for ethnographic research, a personal re-statement of fundamental objectives and strategies. It was, in part, a reaction to recent methodological approaches that do violence to the ethnographic tradition and do not do justice to the analytic possibilities of ethnographic fieldwork. More positively, I wanted to commend the spirit of ethnographic enquiry, with its demanding intellectual and personal commitments to the everyday lives of ones fellow men and women. That spirit was carried through into the second volume, Thinking Ethnographically (2017), where I outlined some of the key analytic ideas and perspectives that can (and in many cases should) inform ethnographic enquiry. Some of those ideas were classics, others more recent. Together, they were intended to provide the would-be ethnographer with an array of productive ideas.

My intention was not, of course, that any other scholar novice or expert should copy them, or adopt them wholesale. Rather, the aim was to help others to develop their own ethnographic thinking. But I was conscious of the extent to which students and others can undertake fieldwork with little sense of what to do with the data they collect. In the absence of ideas, field research is idle. Each of those books was devoted to encouraging their readers to make a positive commitment to ethnography and its ideas. I know that my ideas and advocacy were not perfectly coherent, epistemologically or methodologically. No matter, they were not works of philosophy, but were intended to provide students and researchers with motivation and ideas, in order to get going and keep going. In the course of this third book I shall not establish a single position. Indeed, I am not greatly given to adopting positions. It is far too easy to get stuck in one position, with consequent loss of flexibility. I certainly do not advocate the slavish adoption of pre-existing perspectives. In any case, the theme of the book is the plurality of textual strategies and conventions, and while I am not uncritical, I do not advocate one single approach.

Now, in this third book, my focus moves from analysis to writing. It is based on the truism that ethnographers reconstruct social realities through their textual practices and conventions. There is an important and intricate relationship between our engagement with a given social world and our reconstruction of those social realities into textual forms. In the real world of research, these divisions into fieldwork, analysis and writing are spurious. They are simultaneous aspects of the research process, and their synchronicity is a particular feature of ethnographic research. But we have to make some such distinctions in order to examine those complementary facets of the research process. There are particular reasons for addressing the textual practices of ethnography. Writing ethnography is far from being a technical activity. It is not simply a matter of writing up our results in a textual vacuum. One needs to recognise: literary models and precedents; textual conventions; distinctive genres associated with particular schools and traditions of field research; fashions in ethnographic style. There exist conventional texts (in the sense that they seem unremarkable to writers and readers), and there are overtly experimental or transgressive texts. (They are all conventional to the extent that they reflect shared assumptions and practices.) There are controversies surrounding the textual conventions and their connotations. In turn, authors have created a proliferation of styles and texts, many of which depart from the traditionally conventional. Claims and counter-claims concerning ethnographic representation have been bandied about in the relevant disciplines. These phenomena deserve appraisal in their own right. They also reflect back on our more general interests in undertaking ethnographic research in the first place. There are, therefore, several major reasons to examine the processes of ethnographic composition, and the texts that are generated. They have a certain intrinsic interest too. Since, as social researchers, we all have to write, then it can be engaging and illuminating to examine just how our peers and predecessors have set about the relevant tasks.