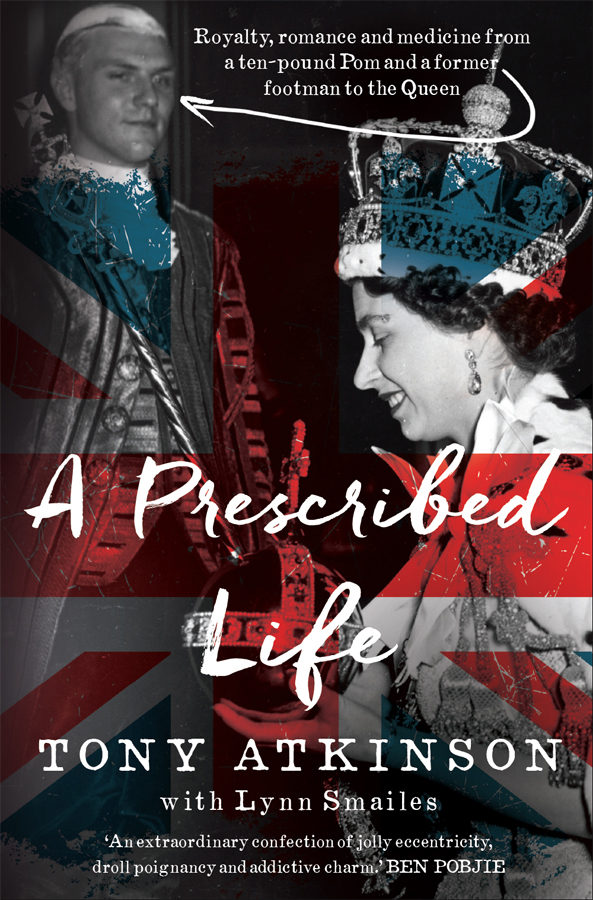

Lynn Smailes is a Melbourne writer, teacher, manuscript editor, reviewer and writing mentor. She was the President of the Victorian branch of the Fellowship of Australian Writers for five years, and the editor of The Australian Writer for three years.

Published by Affirm Press in 2016

28 Thistlethwaite Street, South Melbourne, VIC 3205

www.affirmpress.com.au

Text and copyright Tony Atkinson & Lynn Smailes, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of the publisher.

All reasonable effort has been made to attribute copyright and credit. Any new information supplied will be included in subsequent editions.

All reasonable effort has been made to verify the assertions in this book. Events, locales and conversations are recounted to the best of the authors recollection.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

available for this title at www.nla.gov.au.

Title: A Prescribed Life / Tony Atkinson & Lynn Smailes, authors.

ISBN: 9781925344738 (paperback)

Cover design by Christa Moffitt, Christabella Designs

Typeset in Sabon 12/18 pt by J&M Typesetting

The paper this book is printed on is certified against the Forest Stewardship Council Standards. Griffin Press holds FSC chain of custody certification SGS-COC-005088. FSC promotes environmentally responsible, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the worlds forests.

For Lucy, Sarah, Kate, Sophie and Rosemary

Contents

The Importance of Not Being Earnest

Now produce your explanation and pray make it improbable.

Algernon, The Importance of Being Earnest, Oscar Wilde

As a baby I was put in a wire cage suspended out of a sixth storey window at the back of our house. Every morning I was coaxed into the cage, and the window was closed. I stayed there most of the day.

The cage was made from wire, lined with a plywood roof for protection from rain, and had a plywood floor. I had an unhampered view of the back of surrounding houses as I played with my teddy bears, rag books and building blocks. Toy soldiers were for indoors only, because they escaped through the bars. I was never bored. I never felt caged. Apart from short breaks for feeding and changing my nappies, I would play in there until I was cleaned up by Nanny at teatime and brought down to be shown off to my parents.

The window cage for babies was patented in 1923 by Emma Read, an American, and I adored mine. I was astonished it was named as one of TIME magazines 50 Worst Inventions, alongside such aberrations as Agent Orange, Smell-O-Vision, Hair in a Can and the Hula Chair. It was the ultimate cubby house, and I loved waving to people below.

When I outgrew the cage, I learned to open the window to dangle by my fingers from the sixth-floor ledge. This alarmed some of the people from the houses at the back of ours. Go back! Go back! they would yell. A frenzy of doorknocking would be unleashed in our street to find out which house this poor, endangered child belonged to. When the clamour arrived on our front doorstep, it didnt take my mother long to work out it was her son. Once alerted, she climbed the stairs and calmly lured me back into the house with a bar of chocolate. In seconds I would heave myself through the window and be by her side. One day she came with a bar of chocolate in one hand and a hammer in the other to nail the window shut.

My mother, Marjorie, may have welcomed these early signs of adventurousness as a foil for the indulgence lavished on me as the youngest child and the only boy in the family. She gave birth to me a few weeks after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, a metaphor for the bull-or-bear run that has been my life. The obstetrician who delivered me had been called to our home in the middle of a West End performance of The Importance of Being Earnest . Mum rejected his suggestion that Ernest would be a suitable name for me. The outward expression of earnestness was not encouraged in my family.

Mum was one among many generations of mothers influenced by early twentieth-century child-rearing theories advocated by people like Frederic Truby King. These theories prescribed strict feeding and sleeping routines, long stints in the open air, denying attention to crying babies, and building character by avoiding excessive cuddling and giving children too much attention. There was no garden at our house, and the window cage solved the problem of providing fresh air for me.

I had not reached double figures when Mum dropped me off to have a surgical procedure at a London hospital and left me with instructions to find my own way home. It was my first experience of anaesthesia and my reaction to the ether made me vomit on the top deck of the bus on the return trip.

At the age of four, I began boxing lessons at the Polytechnic Boxing Club in Regent Street. The Polytechnic had a proud history of producing amateur boxing champions. Mum handed me over to the trainer and headed off shopping. I was dwarfed by the hulks lumbering around in the locker room and felt smothered by the pungent odour of their sweat as I changed into my singlet and gym shoes. The trainer gave me a lesson before thrusting me into the ring to spar with one or other of these giants. They were very gentle with me. But from the edge of the ring, the trainer would yell instructions: Keep your hand up. Cover your chin. Nobody had ever yelled at me before.

At home I had my own boxing gloves and a punching bag that swung from a contraption attached to my head. If I missed a punch, the bag would hit me in the face. While Mum was not physically demonstrative of her affections, she liked sparring with me.

My father was a general practitioner. He used his full name, Cecil Hewitt Atkinson, to distinguish himself from another doctor with a similar name who performed illegal abortions. Dads service in World War I meant he was in his mid-twenties before he started training as a doctor, supporting himself with a variety of jobs.

One involved joining the Civil Constabulary Reserve as a special constable during the General Strike of 1926. The strike occurred against the backdrop of fears about the spread of Russian Revolution-style Communism, and social divisions exacerbated by tough economic conditions. The 1012 per cent unemployment rate throughout the 1920s had not spread evenly across the United Kingdom, and in industrial areas unemployment was much higher. The strike was triggered by a dispute in the coal industry. The owners of the mines wanted to cut miners wages by 13 per cent and add an extra hour to their shifts.

Tony Atkinson was born in London in 1929. He worked as a casual footman for the Royal family and as a waiter in London while he was training to be a doctor at Guys Hospital. Tony and his wife, Terry, brought their young family to Australia in 1962, and they settled in the northern suburbs of Melbourne where he practised as a specialist anaesthetist until 2014. He is a former President of the Medico-Legal Society.

Tony Atkinson was born in London in 1929. He worked as a casual footman for the Royal family and as a waiter in London while he was training to be a doctor at Guys Hospital. Tony and his wife, Terry, brought their young family to Australia in 1962, and they settled in the northern suburbs of Melbourne where he practised as a specialist anaesthetist until 2014. He is a former President of the Medico-Legal Society.