Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

Copyright 1950 by Bollingen Foundation Inc., New York, N.Y., and

renewed 1978 by Princeton University Press; new preface

1993 by Princeton University Press

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Horapollo.

[Hieroglyphica. English]

The hieroglyphics of Horapollo / translated by George Boas.

p. cm.(Mythos)

Originally published: New York: Pantheon Books, 1950. (Bollingen

series; 23).

ISBN 0-691-00092-1 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-0-691-21506-8

1. EmblemsEarly works to 1800. 2. SymbolismEarly works to

1800. 3. HieroglyphicsEarly works to 1800. I. Boas, George,

1891- . II. Title. III. Series: Mythos (Princeton, N.J.)

IV. Series: Bollingen series; 23.

BL603.H6713 1993

291.3'7dc20 93-8657

R0

FOREWORD (1993)

Anthony Grafton

Egyptlike the other countries of the ancient Near Easthas played a paradoxical role in Western thought. Greek writers often represented Egyptians, like Ethiopians and other non-Greeks, as barbarians, swarthy, cunning, and prone to ungovernable anger. Even the Greek-speaking Egypt of the Hellenistic period seemed Oriental, a place of alluring scents, strong spices, and strange magical practices. The temptations of Cleopatras Egypt, according to Roman writers, explained the failures of Mark Antony and dramatized the incorrupt military virtues of Caesar and Augustus.

Stereotypes reigned, but they were very ambiguous. Many of Greeces most original intellectuals respected Egypt as the source and repository of profound learning about gods, the universe, and humanity. The powers of traditional Egyptian culture fascinated Western historians, philosophers, and scientists, who admired what they saw as the millenial continuity of Egyptian life. In particular, Egyptian philosophy seemed to them older and deeper than their own. They liked to tell stories about the philosophical journeys to Egypt in the course of which Solon, Plato, Eudoxus, and even Julius Caesar had learned the mysteries of being, the stars, and the calendar. Greek historians and ethnographers informed their readers of the wonders of Egypts great buildings and strange customs. The rulers of imperial Rome imported the grandest and most mysterious of Egyptian relics, the obelisks, to Rome and Constantinople, where they gave dramatic emphasis to sections of the empires capital cities and provided tangible evidence of Romes dominance of the world.

In the first centuries of the Christian era, Greek writers working with scraps of information and Egyptian thinkers scrambling to assemble the barely recognizable fragments of their shattered ancestral culture richly elaborated the myth of Egyptian wisdom. The process was complex and protracted. Many of those who took part in it were liminal figures, like Chaeremonthe strange Alexandrian scholar, a Stoic and anti-Semite, who rose to become Neros teacher in Rome. The surviving fragments of his work on the hieroglyphs emphasize the austere wisdom of the ancient Egyptian priests. He portrayed them as ideal barbarian sages, disciplined and self-denying. Unfortunately he drew his adjectives not from experience but from the stock of commonplace terms applied by Hellenistic writers to a gaggle of exotic clerisies, all of whom they imagined as leading the lives of Greek philosophers. Chaeremons Egyptian sages could as well have been Indian gymnosophists, Gallic Druids, or Zoroastrian priests as Egyptian hierogrammateis. But he also insisted on the uniqueness of Egypts traditions, and provided glimpses of real Egyptian rituals and explications of genuine Egyptian hieroglyphs. His work became a complex tapestry in which genuine and spurious threads, native traditions, and foreign stereotypes were inextricably interwoven.

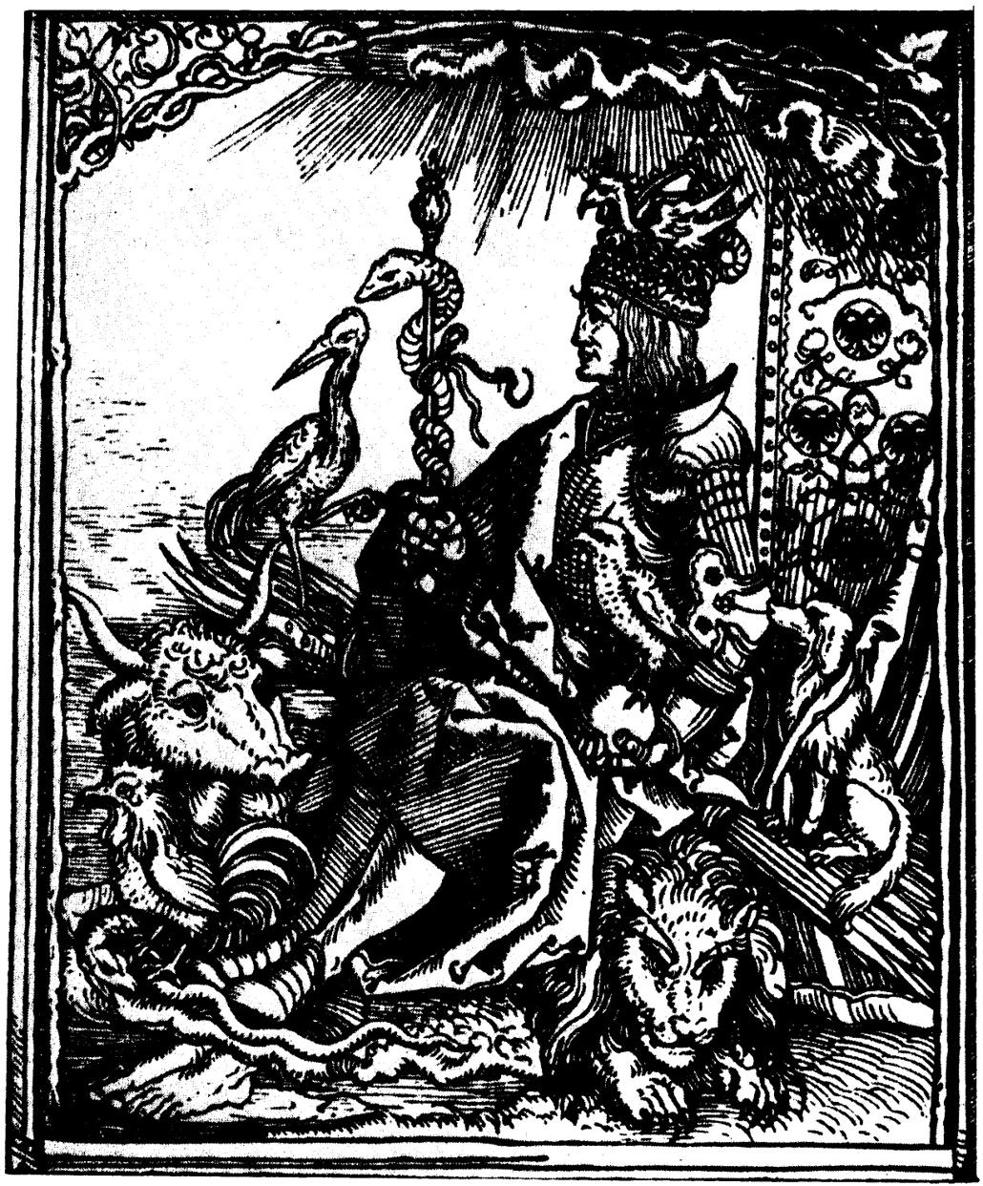

No facet of traditional Egyptian culture occupied a more prominent placeor a less accurate onein scholars mental panoramas of the ancient world than hieroglyphs. By early in the Christian era few scholars, even in Egypt, could still write or read a hieroglyphic text, much less explain the ideographic and phonetic nature of Egyptian script to foreigners. No Greek whose work is preserved ever learned to read hieroglyphs. But culture, like nature, hates a vacuum. Historians, philosophers, and fathers of the church wove a new tale about Egyptian writing, ably summarized by George Boas in the introduction that follows. The priests of Egypt, they decided, had created a written language perhaps older than, and certainly different from, any other: one in which each image expressed each concept with matchless clarity, because it was a natural, not a conventional, sign. For not as nowadays, said the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, did the ancient Egyptians write a set and easily learned number of letters to express whatever the human mind might conceive, but one character stood for a single name or word, and sometimes signified an entire thought.... By the picture of a bee making honey, they indicate a king, showing by this symbol that a ruler must have both sweetness and yet a sharp sting. The uniquely profound message of Egyptian philosophy had been cast in a uniquely profound medium.

This misleading, foreign viewpoint inspires not only scattered comments in Diodorus Siculus, Ammianus, and other texts but the entire text of Horapollos Hieroglyphicathe one surviving ancient work that concentrates on and explains a large number of Egyptian hieroglyphs. The book seems to have been written in Egypt by Horapollo, the son of Asclepiades. Asclepiades and his brother Heraiscus, the sons of an older Horapollo, were cultivated Hellenists who lived in Alexandria in the fifth century A.D. Both men studied the native traditions and gods of Egypt as well as Greek philosophy. Heraiscus wrote hymns to the gods of Egypt and tried to prove the basic concord of all theologies.