Routledge Revivals

Letters to a Friend

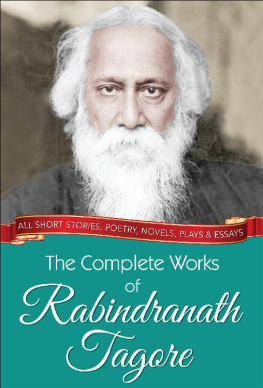

This title, first published in 1928, is a collection of letters from the Bengali polymath Rabindranath Tagore to C. F. Andrews. The letters have been divided into several chapters, accompanied by introductory notes by Andrews, and provide the reader with an expression of Tagores anxiety about modern civilization and political life in India. This book will be of interest to students of history.

Letters to a Friend

Rabindranath Tagore

Edited with

Two Introductory Essays by

C. F. Andrews

First published in 1928

by George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

This edition first published in 2015 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1928 Rabindranath Tagore

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 29010514

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-90953-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-69395-8 (ebk)

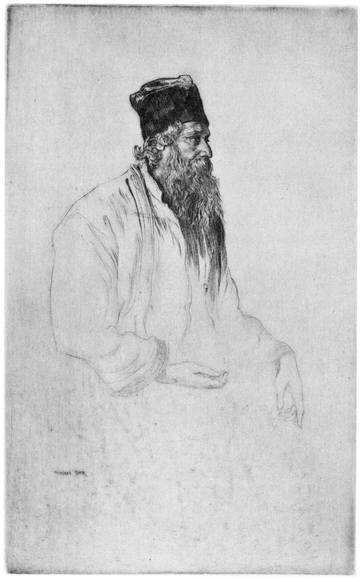

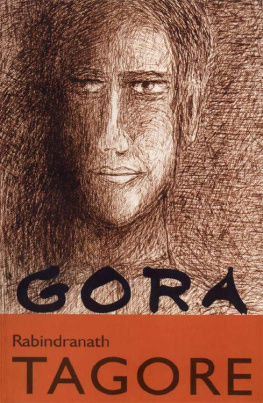

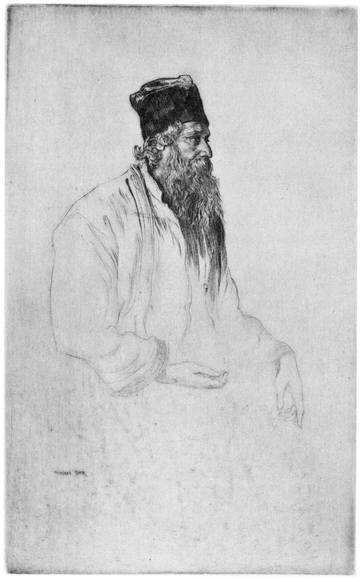

Rabindranath Tagore

From the dry point by Muirhead Bone

Rabindranath Tagore

LETTERS TO A FRIEND

Edited with

Two Introductory Essays by

C. F. ANDREWS

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

UNWIN BROTHERS, LTD., WOKING

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1928

TO

THE MEMORY OF

W. WINSTANLEY PEARSON

THE letters contained in this volume were written to me by Rabindranath Tagore during the years 1913-1922. Many of them were published in India, in the Modern Review, and also in book form, under the title Letters from Abroad. The present volume represents an entire revision and enlargement of that book, of which only a few copies reached England, The material has now been divided into chapters, with a brief explanatory summary of the circumstances in which the letters were written.

It is a pleasure to me to thank Mr. Ramananda Chatterjee, editor of the Modern Review, and Mr. S. Ganesan, publisher, Madras, for permission to use the letters included in this volume, which have already appeared in India. I would also thank Messrs, Macmillan for leave to quote in full the poem on page 52, and Mr. Kelk for his kind help in proof correction.

With the Poet's sanction, this volume has been dedicated to the memory of my own dear friend and fellow-worker at Santiniketan, William Winstanley Pearson. He accompanied me on journeys undertaken with Rabindranath Tagore in different parts of the world, and also was my companion when I travelled with him alone to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Fiji. He was with the Poet in Europe and America at the time when many of these letters were written, and is often referred to in them. His death, owing to a railway accident in Italy in 1923just when he was at the height of his powers of service and lovehas made the fellowship between East and West, for which Santiniketan stands, doubly sacred to us all. He had two homes, one in Manchester and one at Santiniketan, both of them very dear to him. In each his memory is still fresh after the lapse of years.

Any profit from this book will be devoted to the Pearson Memorial Hospital at Santiniketan, which is open to our neighbours, the Santal aboriginals, as well as to the members of the Asram. Willie Pearson's great joy at Santiniketan was to visit these Santal villagers along with the boys of the Asram. He built a school and a well for them and did other acts of service. There could be no more suitable way of preserving his memory than such a hospital.

In conclusion, my special thanks are due to Muirhead Bone and Mukul Dey for their kindness in allowing me to use their drypoint etchings, and to William Rothenstein for the facsimile of the Poet's handwriting. They all shared with me the friendship of Willie Pearson, to whose memory this book is dedicated.

C. F. ANDREWS

October 1928

Contents

Illustrations

| ETCHING OF RABINDRANATH TAGORE |

| From the drypoint by Muirhead Bone |

I

THE course taken by the Bengal Renaissance a hundred years ago was strangely similar to that of Western Europe in the sixteenth century. The result in the history of mankind is likely to be in certain respects the same also. For just as Europe awoke to new life then, so Asia is awakening to-day.

In Europe it was the shock of the Arab civilization and the Faith of Islam which startled the West out of the intellectual torpor of the Dark Ages. Then followed the recovery of the Greek and Latin Classics and a new interpretation of the Christian Scriptures, both of which, acting together, brought the full Reformation and Renaissance.

In Bengal it was the shock of the Western civilization that startled the East into new life and helped forward its wonderful rebirth. Then followed the revival of the Sanskrit Classics and a reformation from within of the old religions. These two forces, acting together, made the Bengal Renaissance a living power in Asia. In Bengal itself the literary and artistic movement came into greatest prominence. Rabindranath Tagore has been its crown.

II

Early in the nineteenth century the burning question in Bengal was whether the spread of the English language should be encouraged or not. Macaulay's famous minute, written in 1835, fixed the English tongue as the medium for higher education. "Never on earth," writes Sir John Seeley, "was a more momentous question discussed." The phrase is an arresting one, and appears a palpable exaggeration until we understand the issues involved, not only for Bengal, but for every country in the East.

Macaulay won the victory. Nevertheless, some of his premises were unsound and his conclusions inaccurate. He poured contempt on the Sanskrit Classics; he treated Bengali literature as useless. In expressing these opinions he committed egregious blunders. Yet, strangely enough, in spite of his narrow outlook, his practical insight was not immediately at fault. The hour for the indigenous revival had not yet come. A full shock from without was needed, and the study of English gave the shock required.

But the new life which first appeared was not altogether healthy. It led immediately to a shaking of old customs and an unsettlement of religious convictions, carried often to a violent and unthinking extreme. The greatest disturbance of all was in the social sphere. A wholesale imitation of purely Western habits led to a painful confusion of ideas. It was a brilliant and precocious age, bubbling over with a new vitality; but wayward and unregulated, like a rudderless ship on a stormy sea.