Dr Sarvepalli

Radhakrishnan

Published by

NIYOGI BOOKS

D-78, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I

New Delhi-110 020, INDIA

Tel: 91-11-26816301, 49327000

Fax: 91-11-26810483, 26813830

email:

website: www.niyogibooksindia.com

ISBN: 978-93-83098-94-1

Year of Publication: 2015

First Published in India by Good Companions, Vadodara, 1961

All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission and consent of the Publisher.

Printed at: Niyogi Offset Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I first became acquainted with Rabindranath Tagores writings in the year 1912. His Gtnjali and Sdhan made a deep impression on me. I wrote two articles in The Quest, explaining his philosophy of life as a genuine manifestation of the Indian spirit. Tagore was good enough to observe that these essays were eminently satisfying, characterised as they were by sympathetic understanding and lucid exposition. Heartened by these words I developed my thesis in a book entitled The Philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore.

When I asked him to read the proofs of the book and write an introduction, if possible, he wrote a characteristic reply. It is difficult for me to write an introduction to your book, for I do not know what my duties are in writing it. If they are to make the path easy for readers I am the last person who is competent to undertake such a task. For about my philosophy I am like M. Jourdain who had been talking prose all his life without knowing it. It may tickle my vanity to be told that my writings carry dissolved in their stream pure gold of philosophical speculation, and that gold bricks ban be made by washing its sands and melting the precious fragmentsbut yet it is for the readers to find it out and it would be a perilous responsibility on my part to give assurance to seekers and stand guarantee for its realisation. If a doctor writes a scientific paper on some disease which I harbour in my constitution it would be ludicrously presumptuous on my part to vouch for its truth, for only sufferings are for me and their pathology is for the doctor.

I made his personal acquaintance in the year 1918 when he visited Mysore, and this was after the publication of my book. Thereafter I enjoyed his affection and friendship which became warmer as the years passed and lasted till the end of his life.

The book was reprinted in 1919 but I was reluctant to have further impressions of it as I felt that the work was based on the English writing of Tagore and the translations of his Bengali works. To comment on a writer when I could not read him in the original seemed to me somewhat unfair. Translations, however adequate, generally miss the poetic fire of the original. So I let the book pass out of print after two impressions. But I am now allowing this reprint to be published in view of he demands from various quarters to have it published in this centenary year. It may perhaps be useful as an indication of my approach to philosophical problems nearly 45 years ago.

I joined the University of Calcutta in February 1921 and had opportunities of meeting the poet off and on. While at the University of Calcutta, I felt that there was a great need for the students of philosophy in India to meet together at least once a year, exchange thoughts and stimulate philosophical studies. The Indian Philosophical Congress which has been functioning since December 1925 was the outcome. We were able to persuade Tagore to preside over the first session on 19th December 1925.

India is a country of contrasts. Even a person like Tagore was subjected to carping criticisms. In a letter to M. Romain Rolland, written from Calcutta, Fortunately he made the journey to Oxford.

I listened to his Hibbert lectures in March 1930 at the Manchester College, Oxford, where he emphasised the validity of the ancient wisdom of India. My religion is in the reconciliation of the super-personal man, the universal human spirit, in my own individual being. He taught us a religion of love and humanity, beauty and laughter. Record houses listened to him. Though many did not understand him all were impressed by the magic of his poetry and the music of his voice. His aged face was worn deep with the lines of thought and struggle but on his rapt countenance seemed to glow the radiance of an unrisen day.

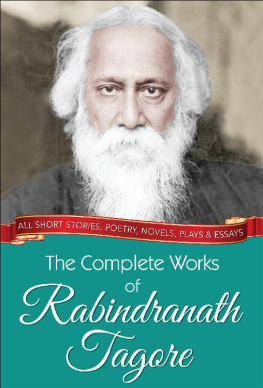

I had the honour of presiding over the public meeting held in the Calcutta Town Hall on the 26th December 1931 in connection with his seventieth birthday celebrations when people from far and near, representatives of Universities and learned bodies, artists, scholars, educationistsIndian and Europeanpaid their homage to the versatility of the great poet; his poetry and prose; his plays and songs; his patriotism and public spirit; his effective work in promoting spiritual freedom, national self-respect and material progress.

In 1933 when I was Vice-Chancellor of Andhra University I invited Tagore to give a few lectures at Waltair under the endowment established by my late friend, Shri Alladi Krishnaswamy. He gave three lectures on December 8, 9 and 10 and they were published under the title Man. I had the pleasure of receiving him again at Waltair on 2nd December 1934 when he addressed the students of the University, and the boys and girls of Sntiniketan gave a few dramatic performances.

When Professor J. H. Muirhead and myself decided to publish in the Library of Philosophy a volume on Contemporary Indian Philosophy we asked Tagore to contribute an article to it. After great hesitation he sent me two papers which we used for the volume. In 1936 I sent him a copy of my Inaugural Address at the University of Oxford. On receipt of this and the volume on Contemporary Indian Philosophy he wrote: I was delighted to read your inaugural address of which you have so very kindly and thoughtfully sent me a copy. India, I think, is now suffering from a surfeit of itinerant professors and preachers in English and the various Continental Universities. There is one hope for me that you are there.

I have received also a copy of the Philosophy compilation and the poet in me feels painfully ill at ease in the company of the philosophers who, I am sure, will find it difficult to tolerate the intruder.

I had the privilege of visiting Sntiniketan in September 1938. He asked me to address his staff and students. About that address he wrote as follows:

I am immensely glad that our students have had this opportunity of coming into personal touch with you and enjoying your marvellous gift of speech and originality of thoughts. I do not wish to spread a shroud of platitudes over the memory of this illuminating address of yours. I only thank you for your kindness in accepting our invitation and coming to see our Ashram which I have been building for forty lonely years with inadequate means and scanty public response, tending it mostly with my love and life which may have an abiding value.

Unfortunately I have been born in Bengal which in its inordinate pride is ever reluctant to acknowledge any merit which sorely needs human sympathy for its complete fulfillment. However, I have come to the end of my days and I cannot expect very much from my destiny. My only claim is that of an artist who is amply rewarded if he is assured by a visitor like yourself whose praise is precious that he has been able to please you.

Next page