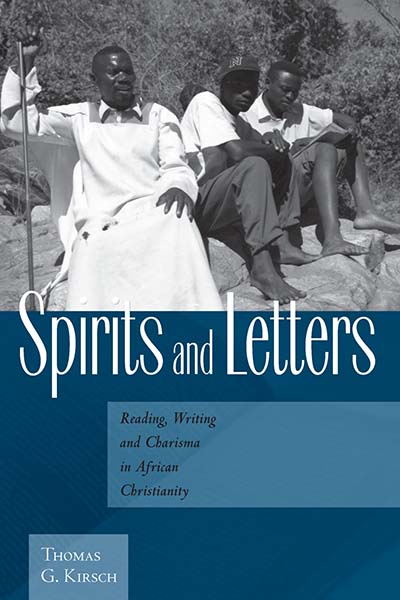

Spirits and Letters

Spirits and Letters

Reading, Writing and Charisma in African Christianity

Thomas G. Kirsch

First published in 2008 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2008, 2011 Thomas G. Kirsch

First ebook edition published in 2011

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kirsch, Thomas G., 1966

/

Thomas G. Kirsch.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-84545-483-8 (hbk) -- ISBN 978-0-85745-142-2 (pbk) -- ISBN 978-0-85745-010-4 (ebook)

1. Christianity--Africa. I. Title.

BR1360.K565 2008

289.94096894--dc22

2008014704

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-84545-483-8 (hardback)

ISBN: 978-0-85745-142-2 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-0-85745-010-4 (ebook)

Dedicated to the nine passengers

who died in the car accident

near Siamungala, Zambia, on 14 June 1999

Contents

List of Illustrations

All photographs Thomas G. Kirsch.

Acknowledgements

The research that forms the basis of this book was conducted over a total of seventeen months fieldwork in Zambia (AprilJune 1993; MarchJune 1995; AprilOctober 1999; AprilJune 2001), and includes archival research in the National Archives of Zambia (NAZ). My research was generously supported by grants from the Free University Berlin (1993), the German Academic Exchange Service (1999) and the German Research Foundation (2001).

In Zambia my greatest debt of gratitude is to my hosts, the members of the Spirit Apostolic Church and my research assistants. Their hospitality and readiness to share their time with me was a constant source of encouragement. I still find my decision to leave their identities anonymous somewhat distressing in view of my wish to express my sincere gratitude to them.

In the academic world thanks are due to Ute Luig for having introduced me to the Gwembe Valley and for supervising my first field research in 1993. I am particularly grateful to Werner Schiffauer, Richard Rottenburg and my wife, Franziska Becker, for their support and thoughtful advice, as well as for creating an intellectually stimulating atmosphere that made anthropology a challenge in the most positive sense of the word. Finally, I would like to thank Robert Parkin for his revision of my English text.

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission to use adapted versions of the following previously published works:

Kirsch, T. 2003. Church, Bureaucracy and the State. Bureaucratic Formalization in a Pentecostal Church of Zambia, Zeitschrift fr Ethnologie 128(2): 21331.

Kirsch, T. 2007. Ways of Reading as Religious Power in Print Globalization, American Ethnologist 34(3): 50920.

Notes on Language

Some remarks should be made concerning language-use. First, verbatim quotations from texts will not be corrected orthographically and mistakes will not be indicated, since this would mean submitting indigenous writings a posteriori to orthographic standardisation. Secondly, although my study mainly deals with contemporary African Christianity, my ethnographic descriptions are written in the past tense. This represents an attempt to account for the particularities of a socio-religious setting that I experienced as extremely dynamic. Thirdly, all quotations from the Bible are taken from the New International Version (South African Edition, 1978).

Most of the villages and individuals I mention have been made anonymous. The designation Spirit Apostolic Church is also a pseudonym. Wim van Binsbergen (1993) has pointed out how the nomenclature of African Independent Churches in Botswana exhibits an endless permutation of always the same few elements, such as in Zion and Apostolic. He thus cautions against analysing a given church name as some sort of deliberate theological statement since it is often ornamental. Similarly here, the substitute name Spirit Apostolic Church should not be read as a theological message of any kind.

Introduction

It had already got dark when the senior leaders of the Spirit Apostolic Church assembled at a fireplace outside the ceremonial grounds. Even though the Good Friday services were not yet finished, the leaders wanted to draw up an administrative schedule for the coming year. The General Secretary put a rough-hewn table near the fire and took a pen, a school exercise book and a ruler to the table. As if they were in an office, the other senior leaders took seats opposite him. In the background choir hymns alternating with sermons and periods of communal dancing could be heard it was the first church meeting that year and most of the congregations were there. The General Secretary had just subdivided the first page precisely into lines when suddenly a pastor approached and asked him to come and help in the ceremonial grounds. One of the young women was showing signs of possession by evil spirits and none of the junior leaders had succeeded in exorcising them. Casually putting his writing implements on the table and excusing himself to the others for the interruption, the General Secretary joined the pastor. He prayed for the woman while laying on hands and started to speak in tongues. After all, he was one of the prominent spiritual healers and prophets of the church. By the time he returned to his desk shortly afterwards the woman had stopped rolling around on the ground. Having cast out the demons the General Secretary now resumed his bureaucratic paperwork.

This episode in a Pentecostal-charismatic church in Zambia in March 1999 touches on the main theme of this book which addresses a long-standing question in the history of ideas and which reconsiders influential conceptual dichotomies in the social sciences and the humanities by way of an examination of reading and writing practices in African Christianity.

In recent years there have been increasing calls for the development of an anthropology of Christianity in which anthropologists who study Christian societies formulate common problems (Robbins 2007: 5). While there is no unanimity among scholars with regard to the achievability of a comprehensive definition of Christianity, it is becoming clear from the emerging body of research that Christian discourses and practices can fruitfully be examined with reference to a set of configurations which in glocalized variations (cf. Robertson 1995) are characteristic of Christianities around the world.

This set of configurations entails varied and interrelated dualities such as body/spirit, immanence/transcendence, materiality/immateriality, visibility/invisibility, presence/absence, this-worldliness/other-worldliness and immediacy/eternity. This list is certainly not exhaustive and some dualities can be construed differently. Nonetheless, the dualisms have in common the fact that they reflect categorical distinctions pertaining to the idea of a foundational gap between human beings and the Divine which is significant for practitioners of Christianity, yet also precarious because it involves dilemmas and paradoxes (Cannell 2006a).