William F ONeill - Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism

Here you can read online William F ONeill - Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1969, publisher: Berkeley, Glendessary Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism

- Author:

- Publisher:Berkeley, Glendessary Press

- Genre:

- Year:1969

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

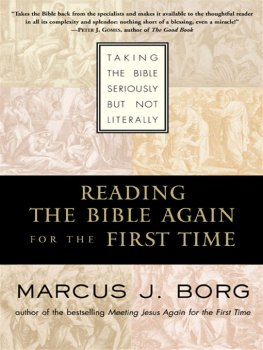

1. The point is made in a remark I have heard attributed secondhand to Peter Gomes, author of a recent best-selling book on the Bible, The Good Book (New York: William Morrow, 1996). Because I am uncertain of Gomess exact words, I do not use quotation marks, but the gist of the statement is this: Has the Bible become a hindrance to the proclamation of the gospel?

2. Mainline Protestant denominations include most of the older Protestant churches: the United Church of Christ, the Episcopal Church, the United Methodist Church, the Presbyterian Church USA , the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (the largest Lutheran body), the Christian Church (Disciples), American Baptists, Quakers, and some others. On the Bible, the Catholic Church has more in common with mainline Protestant churches than with fundamentalist and conservative-evangelical churches.

3. For an important essay on variations within conservative attitudes toward the Bible, see Gabriel Fackre, Evangelical Hermeneutics: Commonality and Diversity, Interpretation 43 (1989), pp. 11729.

4. See L. William Countryman, Biblical Authority or Biblical Tyranny? (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1994), pp. ixx: These Christians imagine that the nature of biblical authority is perfectly clear; they often speak of Scripture as inerrant. In fact, however, they have tacitly abandoned the authority of Scripture in favor of a conservative Protestant theology shaped largely in the nineteenth century. This fundamentalist theology they buttress with strings of quotations to give it a biblical flavor, but it predetermines their reading of Scripture so thoroughly that one cannot speak of the Bible as having any independent voice in their churches. Countrymans book as a whole is strongly recommended.

5. I do not mean that the number of mainline Christians is increasing. As virtually everybody knows, membership in mainline churches has declined sharply over the last forty years. Among the reasons: when there was a cultural expectation that everybody would belong to a church, mainline denominations did very well, for they provided a safe and culturally respectable way of being Christian. Once the cultural expectation disappeared (as it did in the final third of the twentieth century), membership in those denominations declined. But among those in mainline churches, the appetite for modern biblical scholarship is remarkable.

6. Attributed to Jerry Falwell by George M. Marsden, Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991), p. 1. Marsden himself expands the definition slightly: [A]n American fundamentalist is an evangelical who is militant in opposition to liberal theology in the churches or to changes in cultural values and mores. Marsden affirms that fundamentalists are a subtype of evangelicals. For American fundamentalism and its relation to evangelicalism, see also Marsdens Fundamentalism and American Culture (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1980). Both books strike me as particularly illuminating and fair.

7. See the important new study of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim fundamentalism (all understood as reactions to modern culture) by Karen Armstrong, The Battle for God (New York: Knopf, 2000).

8. See the books by Marsden cited in note 6. The origin of a movement explicitly known as Fundamentalism is usually traced to the publication between 1910 and 1915 of twelve paperback volumes known as The Fundamentals.

9. See the very helpful and interesting article on Scriptural Authority in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), vol. 5, pp. 101756. The article is written by a number of authors.

On page 1034, Donald K. McKim notes that the second- and third-generation Reformers affirmed plenary inspiration, the notion that the Bible was directly inspired by God,... in essence a dictation theory of inspiration. Roughly a hundred years after Luther, the Lutheran Johann Quenstedt (161788) wrote that the books of the Bible... in their original text are the infallible truth and are free from every error.... [E]ach and every thing presented to us in Scripture is absolutely true whether it pertains to doctrine, ethics, history, chronology, topography, and so forth.

On page 1035, Henning Graf Reventlow notes that this was a significant change from Luther: [W]hereas for Luther the Bible becomes the living word of God in being preached and heard, in the orthodox systems Scripture in its written form is identified with revelation.

10. For natural literalism and the distinction between it and conscious literalism, see Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith (New York: Harper & Row, 1957), chap. 3, esp. pp. 5153.

11. I owe this very useful phrase to Huston Smith, Jesus and the Worlds Religions in Jesus at 2000, ed. Marcus Borg (Boulder: Westview, 1997), pp. 11617. In his Forgotten Truth (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1976, 1992), especially the first chapter, Smith speaks of modernity as marked by scientism, which he carefully distinguishes from science. Scientism affirms that only that which can be known by science is real. To which I would add that modernity is also marked by historicism: historicism affirms that only that which is historically factual matters. Both perspectives are serious mistakes.

12. For this and other meanings of faith, see my The God We Never Knew (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997), pp. 16871.

1. I cannot demonstrate this, of course, though I think I can make a persuasive case against those who think they can demonstrate Gods nonreality. My study of religious experience in many cultures over many centuries and my acquaintance with contemporary religious experience have led me to the conviction that God is real and can be experienced, and that such experiences occur across cultures and religious traditions. See chapter 2 of my The God We Never Knew (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997).

2. Among recent books, see Paul J. Achtemeier, Inspiration and Authority: The Nature and Function of Christian Scripture (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1999); John Shelby Spong, Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991), esp. pp. 136; L. William Countryman, Biblical Authority or Biblical Tyranny? (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1994), pp. 115.

3. See chap. 4.

4. Lev. 18.22 and .

5..

6. Exod. 4.2426

7. I Tim. 2.915. Virtually all mainline biblical scholars see I and II Timothy and Titus (known together as the pastoral epistles) as relatively late documents written around the beginning of the second century, some forty years or more after the death of Paul. In antiquity, it was acceptable practice to write in the name of a revered figure of the past.

8. The shift in pronouns in the last verse is puzzling. She obviously refers to woman/women; they could refer to women, or it could refer to the children born of childbearing.

9. The Catholic prohibition of ordaining women as priests has a different basis.

10. Exod. 20.17 and Deut. 5.21.

11. Important clarification: I am not saying that the meaning of a biblical text is confined or restricted to what the ancient author or community said. As I will say in the next chapter, a metaphorical reading of the Bible yields meanings beyond the ancient historical intention of the text.

12. For a superb treatment of the meaning of scripture, see Wilfred Cantwell Smith, What Is Scripture? (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993). Smith argues that scripture is a human activity, a phrase with several meanings: the writings that become scripture are produced by humans, are then declared to be scripture by a community, and then function to shape the lives of the people who regard them as scripture. See also the helpful book by John P. Burgess,

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism»

Look at similar books to Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Readin, ritin, and Rafferty; a study of educational fundamentalism and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.