Warfare and the Miraculous in the Chronicles of the First Crusade

Warfare and the Miraculous in the Chronicles of the First Crusade

Elizabeth Lapina

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

An earlier version of chapter 1 appeared in

Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies 38

(2007): 11739.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lapina, Elizabeth, 1979, author.

Warfare and the miraculous in the chronicles of the First Crusade / Elizabeth Lapina.

pagescm

Summary: Analyzes how chroniclers of the First Crusade attempted to represent the enterprise as a holy war. Focuses on accounts of miracles, especially the intervention of saints in the battle of Antioch; explores how the chroniclers related the crusade to biblical eventsProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-271-06670-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. CrusadesFirst, 10961099.

2. MiraclesHistory.

I. Title.

D 161.2. L 37 2015

956.014dc23 2015003524

Copyright 2015

The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by

The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press

is a member of the

Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to

use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy

the minimum requirements of American National Standard

for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for

Printed Library Material, ansi z39.481992.

To Arganthal and Batrice

CONTENTS

This book would not have been possible without the help of a great number of people. Gabrielle Spiegel and David Nirenberg were wonderful teachers when I was a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University and they have been very generous in their guidance and encouragements all these years since my graduation. My debt to them should be apparent in every chapter.

I worked on this book while employed, in succession, by four institutions in three different countries. Receiving the Marjorie McLean Oliver Post-Doctoral Fellowship at Queens University in Kingston, Canada, was a major boon for me, as it allowed me to ease into teaching with a vastly reduced load. Among the faculty at Queens, I would like to thank especially my mentor, Richard Greenfield, for his unwavering support of my work. Two years as a visiting lecturer at Durham University gave me a rare opportunity to interact with a series of medievalists and crusader specialists in the United Kingdom. Although I received a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellowship at the University of Kent in Canterbury for another book, this fellowship gave me much needed time to revise the draft of the present one. Once again, at Kent, I was fortunate when it came to my mentor, Barbara Bombi.

Friends and colleagues too numerous to list have helped me over the years with their advice and good cheer. I particularly appreciate the generosity of Steven Biddlecombe, Barbara Bombi, Clare Monagle, Nicholas Morton, Luigi Russo, Katherine Allen Smith, Carol Sweetenham, and Susanna Throop, who took time to read the drafts of various parts of the manuscript. Anonymous reviewers at Penn State University Press went beyond their call of duty to suggest improvements. Ellie Goodman at Penn State Press kept alive the dream of seeing this project in print. Suzanne Wolk weeded out as many errors as was humanly possible.

I am thankful to my parents, Galina Lapina and Alexander Dolinin, for their unwavering support of my career in general and of writing this book specifically. It is a pity that my grandmother, Alexandra Ivanovna Lapina, will not see it.

I still cannot believe my luck in being able to share this journey with Arganthal Berson and our daughter, Batrice Anna Maria Berson. For the past decade, Arganthal has been there for me every moment, whatever adventures came our way. Batrice tried hard to be understanding of my need to work long hours and was also very good at reminding me that there was more to life than the Crusades. It is a great pleasure for me to dedicate this book to both of them.

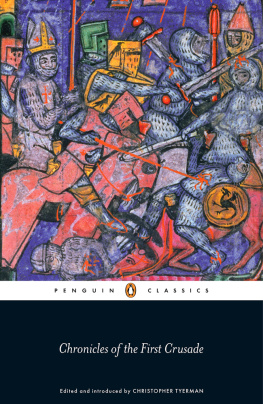

When the news of the capture of Jerusalem on July 15, 1099, reached Europe, the entire Latin world applauded and marveled at the incredible achievements of its soldiers.

Robert and Guibert appear to have believed, this was not a one-time exception but a new opportunity for all present and future knights. Indeed, the conviction that certain wars could be salvific became part of the medieval landscape and reemerged in an ever-expanding number of contexts, both on the frontiers of Latin Christendom and in its hinterlands.

Among the sources that reflect the shift toward the sacralization of warfare that took place during and in the immediate aftermath of the First Crusade, chronicles are the most revealing. No fewer than four participants have left records of the events. In the half century after the capture of Jerusalem, numerous chroniclers and poets used some combination of these four works, as well as other written and oral sources, to produce a series of additional narratives. For the Middle Ages, the existence of such a large assembly of sourceswhich describe the same events but were written by authors from different backgrounds, living in different countries, displaying or concealing different agendas, and working in different stylesis truly exceptional. The possibility of comparing several narratives of exactly the same events allows one to note omissions, additions, free paraphrases, and shifts of emphasis, all of which make each text unique. Although some of the discrepancies could be either accidental or merely stylistic, others point clearly to the heterogeneity of interpretations. Each narrator of the First Crusade probably hoped that his perspective on the event would become the standard one, superseding all others.

In general, as Gabrielle Robert or Guibert, however, stand apart from most other writers of history in the Middle Ages because of their belief, which they must have shared with many of their contemporaries, that God was involved in the enterprise in a much more literal sense than ever before, with the possible exception of the wars of the Israelites. Perhaps even more important, this was the first war believed to have actually transformed the meaning of warfare. But it was not enough simply to say, as Robert did, that the First Crusade was the most important event since the incarnation; it was necessary to prove it. The chroniclers found two ways to adduce proof of the exceptional nature of the crusading enterprise. First, they placed miracles at the center of their narratives. Second, they developed ingenious ways to inscribe the First Crusade in the continuum of sacred history. Although the overarching agendas of most of the chroniclers were the same or similar, both the paths that they chose and the conclusions they reached were remarkably different.

Jonathan First Crusade probably made the theological component more central in its chronicles than ever before.