The Plantation of Ulster

The truth is, they that gape after poor Irishmens lands do what they can to have a colour to beg them(State Papers, Ireland, 1610, p. 415).

These words were written in an appeal for justice, or even the formality of a trial, by one who was betrayed by the English whom he had served. Sir Donnell OCahan had left his own people to seek an English alliance, and was rewarded by an imprisonment of nineteen years, without ever being brought up for trial. He was goaded into a just indignation by rumours that reached him in the early days of his imprisonment in Dublin, of Lady OCahans destitution and insanity, but after a couple of years he was moved to the Tower of London, where he, and other noblemen who were confined because men hungered after their lands, languished away till death gave them release. It will not surprise most of our readers to know that his letters were intercepted and carefully studied with a view to finding something treasonable in them. Truly Irelands share in the privileges of Magna Carta has been a small one.

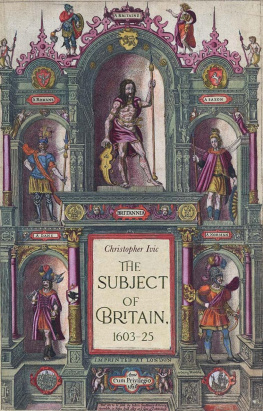

The opening of James Is reign in Ireland was auspicious enough. The battle of Kinsale was an effort of an United Ireland, aided by Spanish troops, to meet and expel the English in the battle-field: it failed, and with it came to an end the hopes of the great Irish lords to do anything by open warfare. James found Ireland decimated by war and famine: some parts like the Ards in the County Down had been literally cleared of their inhabitants. The chiefs were willing enough to submit, if submission meant that they were to become great Palatine lords, with no interference from the Crown in their relations with their vassals, or in the exercise of their religion. The once turbulent Anglo-Irish lords had nearly all conformed to the Protestant religion, and become loyal. The people, with the gaunt figures of famine and desolation that they remembered so well, would have been glad to have peace, if not at any price, at any rate at any price that might allow them to remain in their own land and worship as their fathers had done. By his descent James had claims upon the loyalty of the Irish that could not have been urged for the Tudor line. And it looked at first as if a new era of prosperity was dawning upon Ireland.

James began by a policy of conciliation and toleration. He actually appointed a man as a bishop in 1603, because of his knowledge of the Irish language (this was Robert Draper, Rector of Trim, who was made Bishop of Kilmore and Ardagh). in his imprisonment and his assassination in exile, would naturally make Irish leaders of that time very shy in placing themselves in English hands when a serious charge was made against them.

Juries of the time were pliable, or, if they showed signs of independence, there was a court of Castle Chamber, corresponding with the Star Chamber of English history, that could use means to bring them into line. That the two Earls were innocent of the plot alleged against them is a moral certainty. The fact that when they fled, it was not to Spain they went, seems strong evidence of this. Any evidence of a plot depends on the word of St. Lawrence, Lord Howth, whose character may be judged from what we read about him in the State Papers.

In the subsequent references to the flight of the Earls, even the king himself tacitly dropped the charge of conspiracy, and dwelt upon the disaffection they showed in quitting the kingdom without leave, which was treated in those days as a crime. Sir John Davies says that the Bill laid before the Grand Jury in Donegal was read in public in English and in Irish, so as to discover a great deal of the evidence to all the hearers to the end that all the country might be satisfied that the State proceeded against them upon a most just ground, and that the people, knowing their treacherous practices, might rest assured that their guilty consciences and fear of losing their heads was the only cause of their running away, and not the allurements of any foreign prince. It speaks well for the loyalty of the peasantry to the Earls that the attempts to get up charges against them failed so completely. I shall have to refer later on to the unreality of the religion which the English party tried to introduce by bribes and threats into the land. It is plain that the leaders of Irish government knew of the unreliable character of Lord Howth, who admitted having gone to England looking for employment or pension from the king: but indeed there has never been a time in Ireland when the use of base means has not been practised.

However, the dreary record of the illegalities and confiscations inflicted upon a half-famished nation is somewhat relieved by the grotesque absurdities which the State Papers sometimes reveal. For example, Government stooped to accept the evidence of a professional beggar. This worthys name was Teig OFalstaf, and he had gone to Spain simply to beg his way, and we find the Government solemnly accepting his evidence that he had heard the Irish priests in Spain cursing the Lord Deputy in public service. What did all this tissue of espionage before submission, after rendering homage, and in exile, succeed in proving? Nothing against Tyrone, but much against the persons who employed such unworthy methods. From those days down to the forgery that The Times paraded against Parnell, and possibly even to a later date, England has been industriously cherishing everything that tends to lead her astray about Ireland, and forgetting the solid fact that, in the length and breadth of the Empire on which the sun never sets, there is not another of her colonies or dependencies that she could hold for a week if she applied the methods of Irish government to it.

The idea of colonization was not a new one. It had been tried officially and unofficially in various parts of Ireland. When done officially the attempts had been failures, but the private colonizations had occasionally been successfulfrom the colonists point of view. Early in King Jamess reign Chichester had brought over a number of Englishmen from Devonshire and planted them in Carrickfergus and Malone, near Belfast, and it was undoubtedly this which led to the bold project of colonizing six whole counties in Ulster. If the matter had been left to Chichester it would have taken a milder form. But Sir John Davies began to take a lead in the project, and in the end he became the working agent of the whole affair. He was Irish Attorney-General. This was just the time for unscrupulous and cunning men to rise to power, for practically everything in the country was in a state of transition. It had been even suggested that the standing seat of the Deputy and the law should be translated from Dublin to Athlone, as being the centre of Ireland. The proposal was that the Deputy should have two presidents, one in Munster at Kylmalocke, the other in Ulster at Lyeller (probably for Lyffer or Lifford). Sir John Davies favoured the policy of rooting out the natives from their holdings, for their own good, of course! He says transplanting the natives is like moving a fruit tree, to make it bring forth better fruit, and not to destroy it. His plan was accepted.