First published 2007, 2004, 2001, 1997, 1992, 1988, 1983, 1975 by Pearson Education, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2007, 2004, 2001, 1997, 1992, 1988, 1983, 1975 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringewith

Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, permission, in this textbook appear on appropriate page within text.

This book was set in 10/12 Palatino by Integra Software Services, Inc.

ISBN: 9780131884076 (pbk)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnstone, Ronald L.

Religion in society: a sociology of religion / Ronald L. Johnstone.8th ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-13-188407-7

1. Religion and sociology. 2. United StatesReligion. I. Title.

BL60.J63 2007

306.6dc22

2005038026

Considering the global context within which we live and the prominent role religion has in creating and now changing that context, I have felt it important to be more selective than ever in the treatment of topics and issues utilized as illustrations of sociological principles and theory. This has meant that I have deleted some sections that were in the seventh edition and I have added many. I believe most students are pragmatic and want to see and think about applications and implications of what they read and study, both for themselves and their world. A summary of some specific changes and additions follows.

New introduction and reorganization of .

Revised our working definition of religion, by emphasizing the element of the sacred and de-emphasizing the supernatural, thus including the so-called Isms as religious systems but essentially excluding them from later discussion in the book.

Added treatment of Durkheims discussion of ritual and paid more attention to sociological theory at many points throughout the book.

Interchanged old , to introduce the church-sect typology earlier.

Expanded the chapter on religious conflict because religious conflict in all forms has implications for everyone, regardless of whether they have personal religious commitment or not.

Updated the discussion of the Irish religious conflict, with discussion of the July 21, 2005 Sinn Fein directive to disarm and rely on negotiation and political process to resolve differences.

Made major additions to the chapters on Religion and Politics and Religious Fundamentalism. These include:

a. New Christian Right support for election of local school boards

b. Updating of the U.S. Supreme Court decision on the phrase under God in the Pledge of Allegiance

c. Expanded the explication of Civil Religion and its use by President G.W. Bush in light of the 2004 election

d. Updated discussion of the publics approval/disapproval of abortion

e. Expanded treatment of comparisons of Fundamentalists with Evangelicals.

Updated SES data by religious affiliation from NORC.

Both new and updated discussions in : Women and Religion:

a. Additions to the ordination of women issue in the Catholic Church

b. Updating on female seminary enrollees

c. Expansion of discussion of Wicca/Neo Paganism

d. Another option for fundamentalist women in megachurches

e. Reaction of some Catholic women to the death of Pope John Paul VI.

Expanded discussion of the original intent of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Added discussion of James Cones concept of environmental racism.

Expanded discussion of growth in Black Catholics.

New section on the discrepancy between Catholic doctrine and practice.

Discussion of the accession of Benedict XVI to the papacy.

Included Baptist denominations in the section on Protestant denominations.

Introduced the newest major ecumenical groupChristian Churches Together in the U.S.A.

New discussion and data on the impact of differential birth rates in the growth of conservative denominations.

Added discussion of the impending loss of the Protestant majority position in the U.S.

Discussion of factors affecting growth and decline of various denominations.

Expanded discussion of the priest shortage in the Catholic Church.

Discussion of President Bushs Faith-Based Initiatives.

This eighth edition is probably the most thorough revision in the thirty-year history of this text, but built of course upon the substantial revisions that constituted the sixth and seventh editions. With the exception of a few studies and data sets that I have retained from the 1960s to 1970s, because I have deemed them important for historical or theoretical reasons, research data have been thoroughly updated in the last two editions.

I am indebted to the following faculty for their helpful critical reviews of edition seven and their excellent suggestions for my consideration in creating the eighth edition: Alexander Riley, Bucknell University; James Wolfe, Butler University; Rick Fraser, California State University Los Angeles; and Anson Shupe, Indiana University-Purdue University.

And finally, my enduring gratitude to Arline, who continues so steadfastly supportive beside me in this scholarly endeavor.

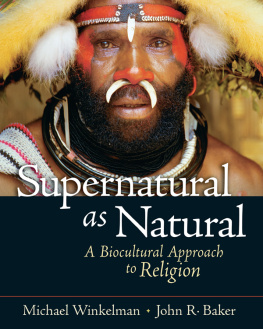

Believers at worship.

Everyone knows at least a little about religion, even if they personally have no affiliation with any religious group. Religion is all around us. In the United States we are aware of the involvement of religion in the political process, particularly as observed in the recent two presidential election campaigns of George W. Bush. We have heard and learned much more about the religion of Islam than we ever did before 9/11. We cannot drive many blocks in any town or city, almost anywhere in the world, without passing a place of worship or monument to religion. In American public schools and Boy Scout troops, every child recites the phrase under God in the Pledge of Allegiance. Eventhough some will say they are not religious, do not belong to any religious group, and do not believe in God, they might nonetheless send you on your way with the benediction may the force by with you. These same people might believe passionately in certain inalienable rights for all people. They will seek justice, equity, and freedom from oppression for all people, holding such beliefs and aspirations as something so universal and important, and worthy of as much passion and conviction, as the most committed Christian believer who strives to bring a friend to Jesus. Might such believers, though not traditionally religious, be religious in much the same way as a typical Christian, Muslim, or Buddhist believer? And so, not only does everyone know at least a few things about religion, but also might everyone actually be religious in one way or another?