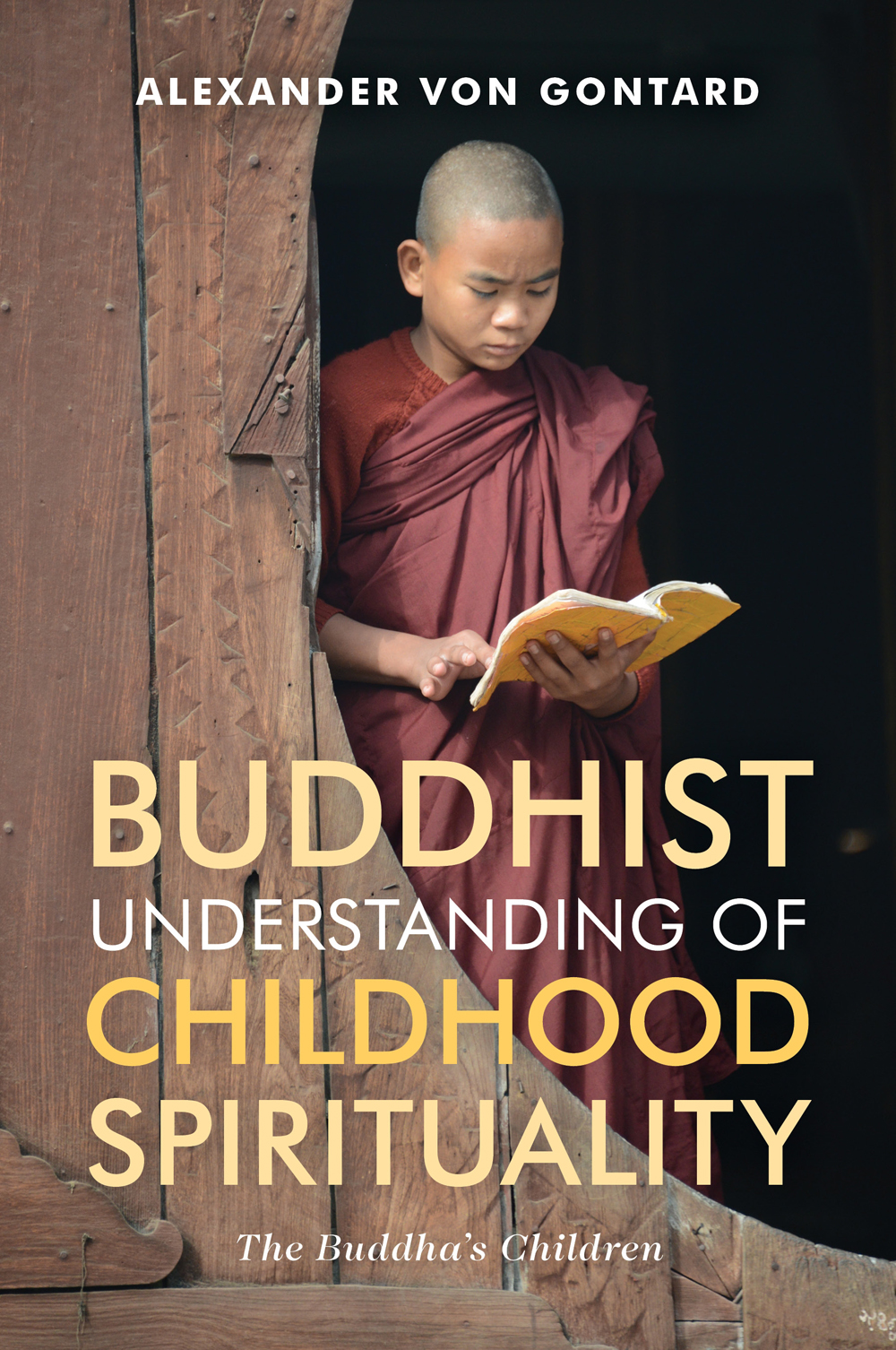

BUDDHIST

UNDERSTANDING OF

CHILDHOOD

SPIRITUALITY

The Buddha's Children

ALEXANDER VON GONTARD

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When I started to write this book, I had a dream: I dreamt I saw an 18-month-old infant a little girl with curly red hair very lively, open, bold, naughty, yet happy. Her mother said, You can have her, but she still has to be born.

I was perplexed by the paradox of this dream: here is this wonderful little girl standing on her feet and ready to explore the world, but she has not entered into this life yet, she is unborn. The unborn is one of the terms the Buddha chose for the spiritual dimension which cannot be expressed comprehensively in words and is therefore referred to in symbols and similes. And the important message is that, like the little girl in the dream, we all exist in both the relative and born, as well as the spiritual and unborn, dimension. As the well-known American psychologist and Dharma teacher Jack Kornfield put it, We are spiritual beings incarnated in human form (2008, p.79). Or, as Thich Nhat Hanh, the much-revered Vietnamese abbot and activist, expressed it, We live in the historical dimension and yet touch the ultimate dimension (2007, p.149).

We have all entered this world without our personal choice or activity, we live our life and will leave it at some time in the future by dying. The spiritual dimension is always present before, during and after life it is spiritual or unborn, as the Buddha chose to call it.

This little girl in the dream alludes to this dimension, as yet being unborn. At the same time, she is very much alive and a perfect symbol for the divine child, the term Carl Gustav Jung chose for one of the most endearing and important archetypes of the human psyche, symbolising a new beginning, wholeness and future developments:

One of the essential features of the child motif is its futurity. The child is potential future. Hence, the occurrence of the child motif in the psychology of the individual signifies as a rule an anticipation of future developments, even though at first sight it may seem like a retrospective configuration It anticipates the figure that comes from the synthesis of conscious and unconscious elements in the personality. It is therefore a symbol which unites the opposite; a mediator, bringer of healing, that is, one who makes whole. (Jung and Kerenyi 1993, p.83)

Finally, in a very restricted sense, this little girl in the dream has been a symbol for this book: originally unborn, it has entered into life, and the process of coming into being has been invigorating and challenging throughout. It has been a new terrain in many ways. Well acquainted as I am with the restrictions of academic writing, this book is much freer, drawing from a wide variety of sources and personal and professional experiences.

As a child and adolescent psychiatrist, psychotherapist and paediatrician, I have had the privilege to listen to and accompany children and their families in life-threatening and existential crises in both physical and mental illness for over 35 years. On the other end of the spectrum, I have also been able to share moments of happiness, exhilaration and ease with them. Just by being open and present, I have been blessed by the trust and openness given to me by young people to explore their spiritual dimension with them. In this context of experiencing and sharing, spirituality has never been esoteric or speculative, but always very real and valid. Spirituality is in a true sense empirical (i.e. based on experience and realisation) and phenomenological (i.e. based on descriptive phenomena). As the Australian Jungian analyst David Tacey remarked, Spirituality does not ask for proofs, because the proof is in the experience itself (2004, p.164). This is precisely the pragmatic approach of the great American psychologist William James (18421910), whose ground-breaking book The Varieties of Religious Experience (2012; first published in 1902) remains so modern and down-to-earth even today. As James showed convincingly, spirituality can be explored, described and communicated just like all other phenomena of the psyche.

A second inspiration for me has been the insights of the Swiss psychiatrist and analyst Carl Gustav Jung (18751961). I remember well when I first read his writings not in German, as they were originally published, but in English. As an adolescent, long before I even considered working as a doctor and psychotherapist, I stumbled across his book Modern Man in Search of a Soul in a small second-hand book store in Windsor. I recently took this book into my hands and saw the words new (even though it was several decades old from 1934) and 1.25 written on the inside cover by the bookseller. I also found quotations which were important to me then and which I had underlined. With respect to symbols, Jung wrote, It is far wiser in practice not to regard the dream-symbols as signs or symptoms of fixed character. We should rather take them as true symbols that is to say, as expressions of something not yet consciously recognized or conceptually formulated (1934, pp.2425). It is only through comparative studies in mythology, folk-lore, religion and language that we can determine the symbols in a scientific way (1934, p.30). And finally, It is only possible to live the fullest life when we are in harmony with the symbols; wisdom is a return to them (1934, p.130).

I was stunned and enchanted by what I read as a teenager. Spirituality or, as Jung called it, the numinous, is an essential archetypal experience of the human soul and can be expressed in symbols. Jung has remained an essential inspiration for me not only to describe, but also to understand, spirituality in a larger context. Through my undergoing Jungian analysis and training in Jungian Sandplay Therapy, which was developed based on Jungian psychology, Jung has become a companion in my professional work.

A third source of inspiration has been the teachings of the Buddha, as reflected in the title of this book. The American psychoanalyst Mark Epstein has described Buddhism as the most psychological of the worlds religions, and the most spiritual of the worlds psychologies (1998, p.16). As a historical person who lived 2500 years ago in Northern India, Siddhartha Gautama (his name before he became enlightened) described a practical, yet universal, way to understand life open to all humans at all ages at all times. The Buddha, as he was called after his own deep realisations, shared his experiences freely. In an open, and yet radical way he invited children, adolescents, men and women to enter into an uncompromising and radical exploration of their lives. As an empiricist, he advised only to accept what one personally has found to be true. Once asked how to know if a person is telling the truth, the Buddha answered:

Do not accept anything because of repeated oral transmission; of the lineage or tradition; it has been widely stated; it has been written in books, such as Scriptures; it is logical and reasonable; of inferring and drawing conclusions; it has been thought out; of acceptance and conviction through the theory; the speaker appears competent; of respect for the teacher. Know what things would be censured by the wise and which, if pursued, would lead to harm and suffering. (Titmuss 1998, p.xi)

In addition to this radical enquiry, the Buddha emphasised subtle ways towards realisation by experience and meditation. I remember well how I intuitively loved to meditate as a child. Lying on my back and remaining still, I just watched the clouds with wonder the constant turning, whirling and towering clouds, painting images on the backdrop of the blue tropical skies of India. Growing up in the Buddhas homeland as I did, the sights, sounds and smells of India have imbued my childhood from birth onwards and still remain alive and fresh. Change, movement and impermanence (such as the constantly transforming clouds) can be realised best in stillness and are cherished experiences of many children. Again, these experiences are not esoteric but empirical in their true sense. They are fresh, spontaneous, and thereby reflect the spiritual essence of the Buddhas teachings. These experiences can be expressed spontaneously in words, symbols and play by children and adolescents. In a way, children and adolescents are more open towards these deep realisations than many adults they are the Buddhas children.

Next page