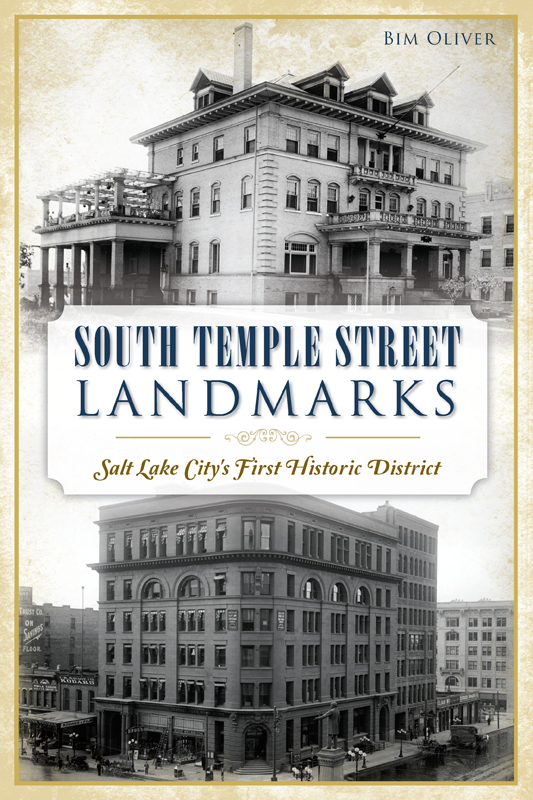

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by John Bennett Oliver Jr.

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43965.937.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016950695

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.771.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Cyndy

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

During the process of researching and writing this book, I often felt that it was a solitary exercise. But it most definitely was not. This book would not have happened without the support and assistance of a number of people.

First and foremost, my thanks to Kirk Huffaker, executive director of the Utah Heritage Foundation, and Barbara Murphy, former director of the Utah State Historic Preservation Office, for encouraging me to explore Utah architecture of the mid-twentieth century, an exploration that led me to South Temple Street of 1925. I was honored that Kent Powell, one of Utahs foremost historians, agreed to review my manuscript. His guidance and insight were invaluable.

Im grateful to Greg Walz of the Utah History Research Center and Sara Davis of Special Collections at the University of Utahs Marriott Library, who were both patient and persistent in tracking down sometimes obscure images. The staffs at the Salt Lake County Recorders Office, the Salt Lake City planning department and the Salt Lake County Archives were always gracious and responsive to my requests for information. My thanks, too, to Bill Browning, Burtch Beall and the family of F.C. Stangl for generously sharing their time in personal interviews.

I want to thank the staff at The History Press, especially Candice Lawrence, who made the publishing process as effortless as it could be for a neophyte like me.

There are other individuals and organizations that Im sure that Ive overlooked, but I hope that they can see their contributions in these pages.

Introduction

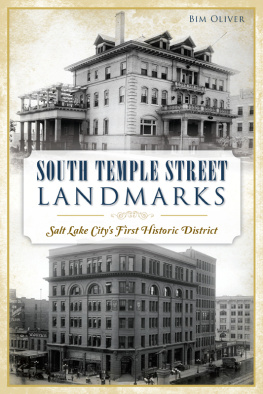

BUILT TO STAND FOR ALL TIME

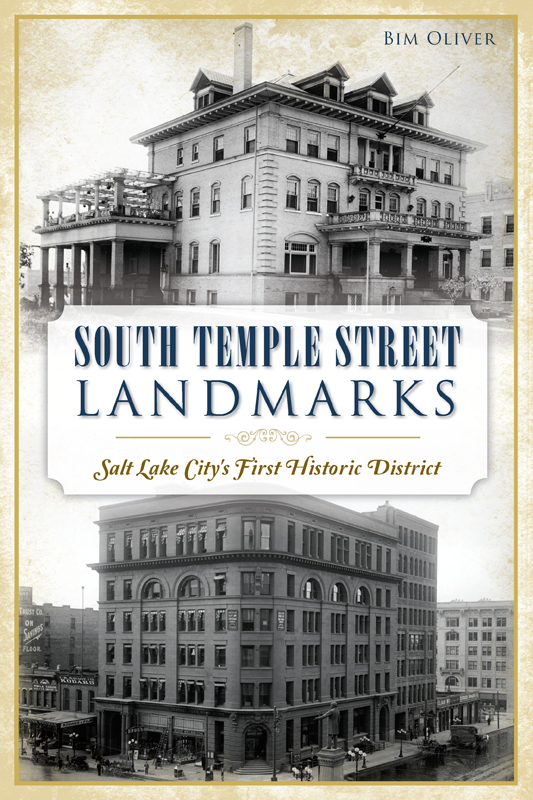

In the spring of 1922, when workers completed demolition of the Gardo House at 70 East South Temple Street, they were likely oblivious to the broader implications of their labors. In addition to dropping the mansions timbers, however, they were also figuratively dropping a curtain on Salt Lakes gilded age. A singular icon of a period known for its icons, the Gardo House had stood on the corner of South Temple and State Streets for a mere fifty years before falling.

Exuberant in its Second Empire frills, it was said to be the finest private residence west of Chicago. Not surprisingly, its transience came as a surprise to the community. One elderly resident observing the demolition remarked that when the mansion was constructed, we all believed that it was built to stand for many years; in fact for all time.

In all its grandeur at the time of its demolition, the Gardo House was not the largest or even the most ornate home in the city. That title would likely have belonged to one of a number of other mansions along South Temple Street. Their presence bestowed an almost mythical character on east South Temple. Named Brigham Street in honor of Brigham Young, it was the home of Utahs rich and famous in the early 1900s, a haven of luxurious estates, lavish parties and extravagant lifestyles. According to historian Margaret Lester, [I]t became the most beautiful thoroughfare between Denver and San Francisco.

But amid the luxurious estates, lavish parties and extravagant lifestyles, change was encroaching on Brigham Street. By the mid-1920s, the party would be over. Attrition, economics and changing social mores would conspire to set the stage for a sweeping transformation. By 1925, as the dust settled on the Gardo House site, the engine of change was churning inexorably along the entire length of South Temple.

Built by Brigham Young, the Gardo House stood for fifty years as a symbol of South Temples affluence and opulence. Utah State Historical Society.

If South Temple were thought in 1925 to have a singular identitythat of Brigham Streetthen the next fifty years would erase that misconception. The changes that would come to South Temple in the middle of the century would be so vast that most of the street would become unrecognizable to the gentleman observing the demolition of the Gardo House. And they would come at great expense to many cherished places along the street that Salt Lake residents assumed would last forever. So much so that by 1975, much of South Temple would be designated by Salt Lake City as a historic district with special protections that would significantly limit the way in which the street evolved from then on. This history, then, is framed by those two years1925 and 1975as the beginning and end of the period of greatest change in the places of South Temple.

South Temples preeminence dated from the earliest days of Mormon settlement. Running past Temple Square, it was given a stature of importance as the major eastwest axis, serving as the only primary eastwest route in early settlement days between the city and Red Butte Canyon, and Fort Douglasand as a parade route for community celebrations. That stature grew as South Temple attracted Utahs richest and most influential citizens as residents, and it became a street that exuded wealth and power. Over time, it also became a bustling thoroughfare between Salt Lakes major centers of activity: downtown and the University of Utah. And it was one of just a few streets that connected Salt Lakes commercial center with its industrial and transportation district.

South Temples significance derived from its unique setting as well. As it travels from the Union Pacific (UP) Depot in the west to Reservoir Park in the east, it runs up a gradual incline. Along its eastern half, South Temple cuts across the base of a steep hill, a topographic distinction that became more pronounced as the city was platted. South Temple came to form the boundary between two neighborhoods where two different street grids meet. To the north of South Temple sat the Avenues with small blocks and lots crowding the steep hillside. To the south, as the terrain leveled, the city spread out in regular large blocks.

This singular settingakin to a topographic podiumcombined with its role as an increasingly important thoroughfare in the rapidly growing city, gave much of South Temple a prestige unmatched by any other street. Even though its identity was, for many years, almost inextricably associated with that of Brigham Street, South Temple was never a single place. It was really a series of places with disparate personalities that ran the gamutfrom dignified and aristocratic to proletarian, even hardscrabble.

Nestled against the University of Utahfrom 1300 East to 800 Eastthe Upper East was quiet and reserved. Its residents were, like the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century mansion builders just down the street, wealthy and influential. But they were not as wealthy and, for the most part, not as influentialand not nearly as ostentatious in their lifestyles. Their homes were certainly large and comfortable but not grand and opulent like the mansions just to the west. While the rest of South Temple would change dramatically between 1925 and 1975, the Upper East wouldquietly and reservedlystay very much the same.

Next page