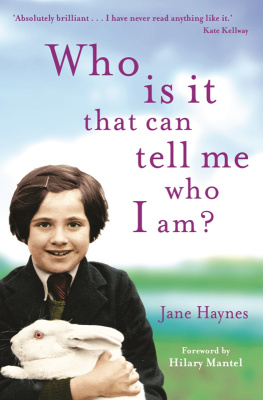

Who is it that can tell me who I am?

LEAR: Who is it that can tell me who I am?

FOOL: Lears shadow.

Who is it that can tell me who I am?

JANE HAYNES

FOREWORD

BY

HILARY MANTEL

CONSTABLE LONDON

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by intheconsultingroom.com, 2007

This edition published by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson, 2009

Copyright Jane Haynes 2007, 2009

The right of Jane Haynes to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library.

UK ISBN: 978-1-84529-972-9

eISBN: 978-1-47211-217-0

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Cover Design: Bob Eames

For my brave grandchildren Daniel and Portia and in memory of their lost father, Jay Abatan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the visible people in this text who have consulted with me and given permission for their narratives to be publicly shared; and to all the invisible people whose trust I have been privileged to gain.

I wish to thank the judges of the PEN/Ackerley Prize, 2008, for shortlisting my book, which was originally self published, and bringing it to the notice of the publishing world.

I should also like to thank my editor at Constable & Robinson, Andreas Campomar, for his sensibility and his commitment to bringing my book to a wider audience, and his colleagues Sam Evans and Hannah Boursnell for their support during this process. Finally, I would like to thank Sarah Lutyens for becoming my agent and for her forthrightness.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Hilary Mantel

W hat will we find, if we step into the consulting room? Who will give us permission to enter, and who owns the house in which the consulting room is contained? As I write this first paragraph, I feel I am poised on the threshold, wiping the dust of the streets from my shoes, about to enter a negotiating chamber, a work space, but also a house, a home perhaps a home away from home.

This is not the first book where a therapist opens her case files, but it is surely the first one where the reader feels so welcomed on an equal basis. Jane Haynes doesnt keep from us her own story her strange childhood with its enfolded and sequential mysteries and she explains how the process of psychotherapy has worked for her. This is in fact a book of stories, and the stories behind them. It is commonplace to observe that we are storytelling animals, and that our urge to make sense of our experience through narrative form is ancient and powerful and remarkably strong. The trouble is, though, that many of our stories are fractured, incomplete and incoherent. Jane operates, to my mind, in the territory of healing fiction; if the teller can fix the broken tale, if he can impart it successfully to the people he means it for, then he or she often finds new energy, authority and a sense of completeness.

I first met Jane Haynes not as a patient but as a fellow practitioner in the art of narrative. I found that talking with her provided insights and illuminations that seemed to come out of the blue, and that it allowed me an imaginative freedom that, as a novelist, I am always struggling for. Writers do not have imaginative freedom as a matter of course. They have many different temperaments and many different strengths, and no doubt some of them feel, as I do, that the rash excesses of creativity must be paid for by a daily life that is prosaic, rational and constrained. From day to day my words are under tight control. All the same, I live by metaphor, and sometimes I like to speak in it. It is wise to pick your audience when you do this. Jane was the audience I picked, and she picked me; both of us, in turn and sometimes together, constitute the performance. We have a working relationship, as people say: a friendship which gets results. The knowledge that such a thing could exist led me from a dialogue with Jane herself to a dialogue with her book, and leads me to recommend it to anyone concerned with the life of the imagination and the healing arts.

Sartre says, Long before we are born, even before we are conceived, our parents have decided who we will be. Certainly we are very young when our particular role in the family is allocated to us. Whether we are the favourite or the misfit, Mummys little helper or Daddys sugar-plum, whether we are a big brave boy or a nuisance or a mouse or a brat, there is an early disjunction between the reality inside our own heads and the picture that is reflected back to us by others. We are handed our masks very early and forbidden to take them off. I think back to my own schooldays, when handwriting was taken to be an indicator of character: what most concerned our teachers was that writing must be consistent. You must present yourself, today, as the same person who sat in that place yesterday; in adolescence it is almost an impossible undertaking, but unless you accomplish it you are unlikely to succeed in any terms the world will recognise. The figures who rule at carnival are the ones who have riveted the masks to their flesh; those who pull them aside are likely to be found at daybreak stabbed in back alleys. We punish curiosity, difference and variation: ambivalence scares us, and perhaps it is because of this that we find the idea of science so comforting.

When people dismiss analytical psychology as unscientific they are really saying that it is subjective. How could it be anything else? Our whole world of experience comes to us subjectively, but that doesnt mean we cant make valid statements about it. We just need to differentiate between qualities that can be measured and qualities which cant without stigmatising the latter as less useful. The hearts electrical pattern can be traced, but not the wayward impulses of love and hate. Yet who could maintain that the latter dont have real effects in the real world? Those who do not believe in what cannot be measured or quantified are on shaky ground; their inner reality is doomed to be alarmingly divorced from the reality of most of those about them.

For most of us do not live our lives in a spirit of scientific enquiry. We live by faith. Its an act of faith when we swallow a pill prescribed for us. If it works were happy, and we dont particularly need to know why. Its the same with the machines that govern our daily lives; we passively consume the marvels they perform. This makes us subordinate intellectually, if not economically to the creators of the machines, the dispensers of the pills. The practice of psychotherapy makes some uneasy precisely because it is not a passive process; the patient is not done-to, is not merely a consumer, but is an active agent of change. The power relations between therapist and patient are far more open to shift and negotiation than they are in the usual process of Western medicine. Those scientists and physicians who define themselves by status rather than by usefulness, by being rather than knowing, will always feel threatened by the psychotherapeutic process, and the assumptions of reciprocity and equality that are written into it by the sensitive and ethical practitioner.

But these arguments which are about the definitions and boundaries of areas of knowledge may be beside the point. If you read a little into the history of analytical psychology, you soon encounter the insecurities of the early practitioners they wanted to be scientists because scientists were respectable and attracted grants and prizes, whereas sages and mystics werent respectable and had to go begging on the roads. But we should have the wit to see beyond the origins of any discipline, and ask ourselves how it has evolved; we dont routinely mock astronomers, because they once thought the earth was the centre of the solar system, and we shouldnt let the intellectual wobbles of the founding fathers distract us from the value of a body of knowledge and a method of practice capable of creative variation and interpretation, which has shown the capacity endlessly to examine its own processes, to re-evaluate and innovate. I am not very interested in the divisions between disciplines, but if I had to make a choice, if I had to categorise, I would argue that the understanding of the human psyche is an art. I dont think that makes it less. We dont sneer at music because it is not a science, nor deride Rembrandt because he didnt paint

Next page