Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

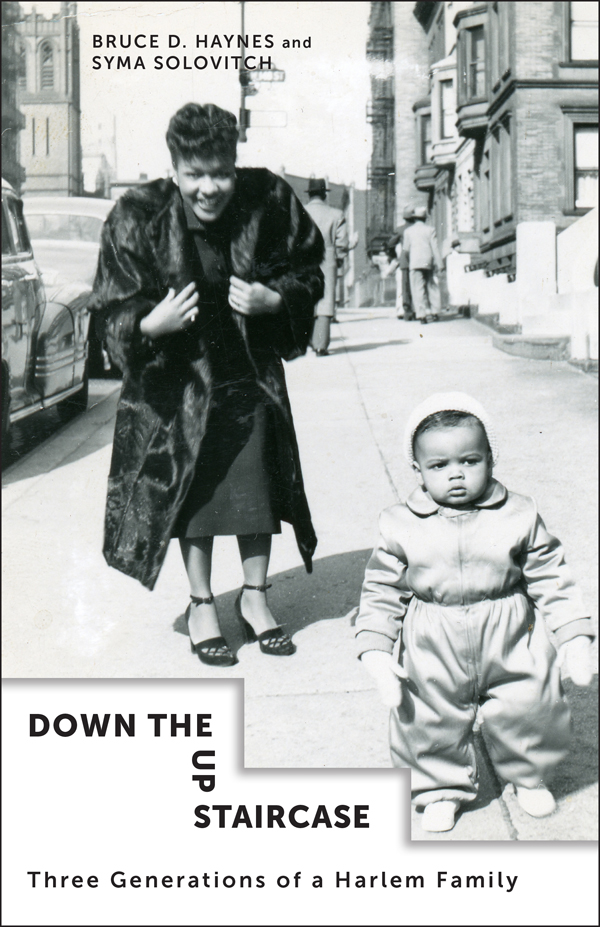

DOWN THE UP STAIRCASE

DOWN THE UP STAIRCASE

Three Generations of a Harlem Family

BRUCE D. HAYNES and SYMA SOLOVITCH

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support for this book provided by Publishers Circle Chair Anya Schiffrin.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54341-5

ISBN 978-0-231-18102-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover photograph: Courtesy of Bruce Haynes

To George III

It was spacious, and I dare say had once been handsome, but every discernible thing in it was covered with dust and mould, and dropping to pieces. The most prominent object was a long table with a table-cloth spread on it, as if a feast had been in preparation when the house and the clocks all stopped together.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

CONTENTS

T his work evolved over many years, and many hands have molded it. Matthew Carnicelli was the first to recognize that our story had market potential, while Richard Scheinin, Diana Jean Schemo, and Sara Solovitchall writers whom we greatly admirenurtured our literary ambitions and gave us tools to transform them into reality.

The wide scope and varied themes tackled in this book called for critical review and feedback, and we acknowledge the collective efforts of several scholars. Sasha Abramsky brought a journalists instincts and a wealth of knowledge about poverty, criminal justice, and social welfare policy, while Bill McCarthy offered his keen sociological eye and expertise on incarceration, crime, and juvenile delinquency. George Lipsitzs extraordinary grasp of urban culture, social movements, and African-American history elevated our work considerably. Ralph Richard Banks pushed us to rethink our framing of several key debates and avoid recreating easy tropes about race in America. He also pushed us hard to give more love to some characters and less of a free ride to others. Sharon Zukin recognized early on the merits of conducting an autoethnographic work on life in Harlem. We also thank Prudence Carter, Kai Erikson, Lance Freeman, Aldon Morris, and Stephen Steinberg, who helped us to refine our arguments and balance the personal, political, and sociological dimensions of the narrative.

Many close friends, including Linda and Stu Bresnick, Jennifer Eberhardt, Rebecca Stein-Wexler, and Tony Wexler, cheered us on from the very start. Some read very raw and early drafts and told us everything we wanted, and desperately needed, to hear. Andy Beveridge offered unwavering enthusiasm and faith in the project.

We are grateful to the outstanding team at Columbia University Press. Editorial Director Eric Schwartz has been an ardent champion for the book, while Todd Manza has conducted painstakingly detailed editing and fact checking.

Certain individuals deserve a category of their own.

One of these is Sara Solovitch, whom we have always depended on for honesty and who deliveredasking tough questions and questioning easy answers. In the final stages, she poured countless hours into editing our manuscript, killing our darlings, and pushing for deeper, harder truths. She was as caring as she was uncompromising in her standards.

And much of this story could not have been told without the testimony of George Haynes III, who shared painful memories and trusted us to do justice to them. We hope we have not disappointed.

I n November 1995, my parents hired a chauffeur and limousine to take them from Sugar Hill, Harlem, to the quaint seashore town of Milford, Connecticut, where my future had finally begun. I had defended my doctoral dissertation that May, married in July, and moved to Connecticut in September to begin teaching at Yale. The limo ride was a once-in-a-lifetime event for my dad, a man who counted kilowatts in pennies and stashed slivers of soapto be used later for bubble bath. But he was old and frail now, and in a final nod to my mother as well as to his own mortality, he spared no expense for this Thanksgiving Day.

We had long since stopped celebrating holidays at our family home, which had no running water on the main floor. By 1995, my parents were living like squatters in their own house. The pipes were frozen and busted, the roof was beyond repair, and despite the size of the housenearly five thousand square feetspace was at a premium. Nothing had been dusted, cleared, discarded, or repaired in more than two decades. What was once a formal parlor that hosted W. E. B. Du Bois and other Talented Tenth elites now held the remnants of my brother Georges failed business ventures. Half-empty cans of spray paint, battered furniture, and broken appliances heaped on top of one another. One might have taken the scene for the final stages of a family moveall stacked up and ready to goexcept that there was a frozenness about it, a sense of havoc in suspension.

My parents had money and could easily have fixed the place, if theyd so chosen. Pop was collecting a modest monthly pension from the New York State Division of Parole and was sitting on some sweet blue chip stocks hed bought on margin back in the 1970s. Mom was still employed, as director of quality assurance at the Washington Heights/West Inwood Community Mental Health Center. But, caught in a whorl of reprisal and censure, my parents had let the house fall to ruin until they were living in near-squalor.

That Thanksgiving morning, my mother would have sponge-bathed with Poland Spring water before unwrapping her silk blouse and Dior suit from their plastic encasements, taking care to keep them from brushing against the dust-thick armoire. She would have fixed her makeup in a dirty cracked mirror in a lightless room before carving a path through the stacks of old newspapers and empty water bottles that littered the floor. My father and her mink coat would be waiting for her on the first floor landing. After locking the double doorsa barricade of latches, padlocks, and deadboltsmy parents would have climbed into the back of the sleek limousine and instructed the driver to circle around to pick up my brother George, who was now living in a halfway house just a few blocks away. Then, up Riverside Drive and the Henry Hudson Parkway and on to the world that my mother had always imagined for me.

They arrived in full fanfare. My mothers arms were laden with the customary bags from Zabars, Citarellas, and Greenbergs Bakery; George followed dutifully with what seemed like a years supply of toilet paper and paper towels. Pop, haggard and unsteady, carried a long rectangular frame. In it was an oil painting of my grandfather, George Edmund Haynes. On its upper right corner was the signature of Laura Wheeler Waring, a prominent Negro portraitist of the Harlem Renaissance. As I came to learn later, the painting was one of twenty-three Portraits of Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin that had appeared at the Smithsonian Institution in 1944 and that toured the country between 1944 and 1946. In the 1960s, most of the portraits were donated to the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian museum, where they remain to this day. The portrait of George Haynes, long buried in our attic, was one of the few that had gone missing.

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York