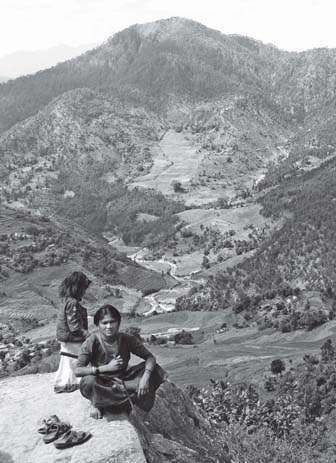

Grazing the Cattle from a High View Point, Western Nepal

(Photo: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine)

The English text of the volume was revised by Bernadette Sellers (UPR 299, CNRS), and the workshop from which it originates was financed by the CNRS, France.

F or those who wish to venture into the Himalayan region a number of Indian or Nepalese travel agencies offer nature and culture tours.1 A nature tour includes trekking or rafting, while a culture tour offers tourists visits to temples or the opportunity to attend festivals. The activities in each category come as no surprise and attest to a broad distinction or categorization now commonly used. Yet interestingly, parallel to the growing use of these categories, they have been the object of heavy criticism over recent decades.

The definition of man as a cultural being as opposed to wild categories of living creatures has long been essential in Western philosophy. This definition was first challenged by the discovery of features in the realm of nature that were once exclusively associated with human culture or civilization. With the discovery of the new world and the wars of religion in Europe, the notions of barbarity and civilization were first relativized from a moral point of view. They were later fully re-evaluated in view of the complexity of primitive cultures. More recently, the notion of animal culture in Ethology has contributed to further blur the limits of what is cultural and what is natural. Similarly, ecologists have emphasized the essential part of human action in many ecosystems hitherto considered natural and have underlined this dimension as being anthropogenic environments. On the other hand, a less widespread school of thought, notably represented by socio-biology, has explored the natural part of culture or the influence exerted by the environment on human societies. Consequently, we are led to consider that animals and landscapes are more cultural than we thought, while humans are more natural.

The boundary separating the two domains of reality called nature and culture in Western languages is therefore subject to considerable interplay on one side and various upheavals on the other. At the same time, several anthropologists have recently shown that these categories are far from universal,2 and have argued that their use introduces an ethnocentric bias in the of non-Western societies.3

This position raises several issues concerning first, the legitimacy of the use of a concept unknown in a culture to describe its reality, and second, whether or not it may throw light on the culture being studied. In fact, this is also true of numerous notions and concepts which are commonly used in Social An thropology,4 and more generally, of the use of a particular language to describe a human reality which is not formulated in it. Yet, before reaching this dead end, another problem emerges that is becoming increasingly difficult to set aside in current anthropology: it involves the introduction of new ideas or the modification of local concepts in most human societies, due to the influence of Western languages through globalization. This striking phenomenon occurs when in some parts of Social Anthropology, the tendency is to privilege the study of groups least contaminated by other cultures or to select only seemingly genuine material.5 This has resulted in a paradoxical situation with regard to the nature and culture issue. Indeed, we now face a situation whereby traditional subjects for anthropological study, i.e., groups calling themselves Indigenous Peoples, have started organizing themselves politically on the basis of their specific link to nature (whether or not they have borrowed the concept),6 and to oppose the groups and institutions whom they accuse of having deprived them of their land and rights. This opposition is expressed by the very opposition of nature and culture, but this dichotomy is denied as being part of the Indigenous Peoples world conception.

Following a long and complicated history of the uses and understandings of an expression such as children of nature, for instance, a point has been reached where, when an aboriginal poet recalls, Children of nature we were then,7 an anthropologist speaking of the same people asserts,8 Children of nature they are not. Of course, when placed in their contexts of enunciation, the former explains that they were happier before colonization, while the latter seeks to show that the people he studies are of a complex culture. Yet, the question remains that the debate regarding nature in Social Anthropology seems out of phase, even in contradiction with contemporary Indigenous Peoples statements.

Numerous publications emanating from all over the world, including Europe, attest to the existence among Indigenous Peoples of a political trend using an opposition or dichotomy nature versus culture, even if, in many cases, the dichotomy is ascribed by Indigenous Peoples to groups from whom they are willing to distance themselves. To take one example among many, Katerina, an advocate for the Macedonian Indigenous Peoples rights, claims:9