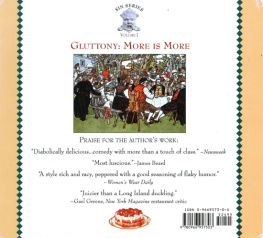

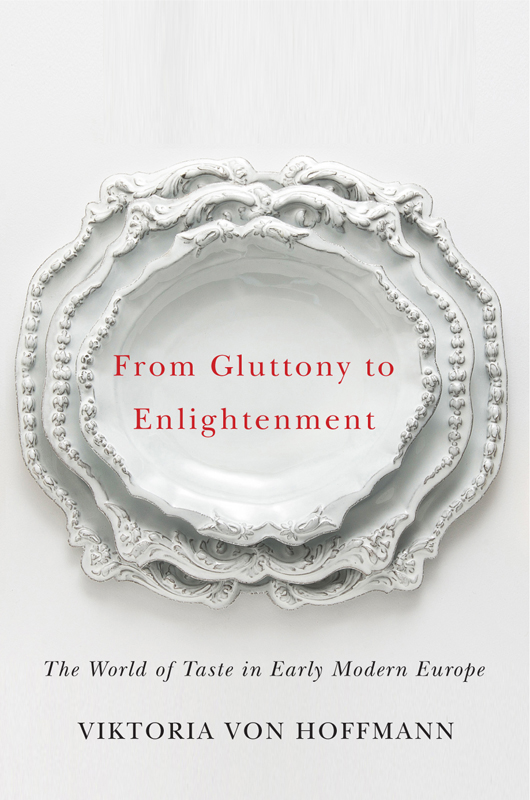

From Gluttony to Enlightenment

STUDIES IN SENSORY HISTORY

Series Editor

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Series Editorial Board

Martin A. Berger, University of California at Santa Cruz

Constance Classen, Concordia University

William A. Cohen, University of Maryland

Gabriella M. Petrick, New York University

Richard Cullen Rath, University of Hawaii at Mnoa

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Expanded, revised, and translated edition of Goter

le monde: Une histoire culturelle du got lpoque

moderne , published in French by PIE Peter Lang, 2013.

2016 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953811

ISBN 978-0-252-04064-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-08214-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-252-09908-3 (e-book)

Acknowledgments

The aim of this book was initially to provide an English translation of my first book, Goter le monde: Une histoire culturelle du got lpoque moderne (2013), a history of taste in early modern Europe. However, writing on taste in another language made me think about related issues in a different way. This in turn was compounded by the experience I was gaining in the field while reading in other areas of scholarship, which helped me bring more details and texture to my inquiry, thus expanding upon some of the implications of my earlier work. I was also fortunate to receive insightful and encouraging reports from the two readers for the University of Illinois Press who commented on earlier versions of this book. These readers had been very carefully and wisely chosen, and provided many valuable comments and ideas that helped me reshape the manuscript and publish, in the end, a different book. The title From Gluttony to Enlightenment: The World of Taste in Early Modern Europe is only one among many suggestions provided by the first reviewer, who read the entire manuscript, for which I am particularly grateful.

Writing this book has been a long-term project during which I acquired numerous debts, the greatest of which is to Carl Havelange, who has been my supervisor, collaborator, and friend for many years now. With wit and enthusiasm, he introduced me to the wonderful research field of sensory history many years ago; the idea of this research on taste and eventually of this book stemmed from the many inspiring discussions I had with him. I am immensely grateful for his enlightening comments, kind critiques, invaluable guidance, and encouragement. I owe him more than I can say.

This book has also benefited enormously from the input of scholars who generously read and commented on part or all of its many drafts. For insightful observations, extensive commentaries, invigorating conversations, and tremendous support, I would like to thank especially Franz Bierlaire, Annick Delfosse, David Howes, Peter Scholliers, and Emma Spary. I would also like to extend particular thanks to David, who first suggested that I submit a book proposal to the Studies in Sensory History series. Moreover, all these years working on taste gave me numerous opportunities to discuss my work in progress with many scholars. At different times I greatly benefited from the advice and suggestions of Der-Liang Chiou, Ralph Dekoninck, Michel Delville, Frdrique Desbuissons, Alain Dierkens, Marie-Luce Glard, David Gentilcore, Allen Grieco, Marie-Elisabeth Henneau, Pierre Leclercq, Isabelle Parmentier, Liliane Plouvier, Florent Quellier, David Szanto, Nolie Vialles, Georges Vigarello, and Allen Weiss. My other debts are too numerous to list, but I am also grateful to the many departments, seminars, and colloquiums that gave me the opportunity to discuss my work in progress and helped me refine my work. To all go my warm and sincere thanks.

Writing a book in another language has been a challenge and a very rewarding experience. I would like to acknowledge the assistance I received from English native speakers who helped me improve the quality of my writing at different stages of this work. My sincere thanks go to Sara E. Wilson, who read and commented upon an earlier version of the entire manuscript, for which I am very grateful. I would also like to thank Scott A. Barton, who read the first draft of . Portions of this book were edited in French in my book Goter le monde ; I thank Peter Lang for permission to use this material. I also wish to thank Mark Smith and Willis Goth Regier from the University of Illinois Press, who responded with such enthusiasm to the project of this book, and Laurie Matheson, Marika Christofides, and Julianne Rose Laut for their valuable contributions in finalizing the manuscript. Last and foremost, warm thanks to Ann Beardsley and Jennifer L. Comeau, who both displayed such a sharp eye in their thorough reading of the last draft of the manuscript.

Most of this research was funded by research fellowships from the Belgian National Fund of Scientific Research (F.R.S.-FNRS) and the University of Lige. I would like to express my gratitude for that support. I would also like to extend my thanks to the staff of the many libraries I have been working in during all these years, in particular from the University of Lige, Bibliothque Nationale de France (Paris), Bibliotheca Hertziana (Rome), cole Franaise de Rome, Concordia University (Montreal), and the University of Cambridge. For permission to reproduce pictorial material in their keeping, I thank the Master and Fellows of St Johns College, Cambridge; the University of Glasgow Library; and the University of Lige, Bibliothque Alpha.

In the end, I would like to mention the encouragement and warm friendship of my colleagues and friends. I owe special thanks to Pierre-Franois Pirlet, Anneke Geyzen, Amandine Servais, Mat Molina-Marmol, and Lucienne Strivay for their kindness, suggestions, support, and never-ending enthusiasm.

I would also like to thank my mother, Vronique de Lamalle; my father, Boris von Hoffmann; and my siblings, Astrid, Nikolai, and Harry. Food, taste, and cuisine have always been an important part of my familys life and culture, which is most likely the reason I ended up working on taste and the senses. This book is dedicated to them all, in memory of past and future lively discussions on taste and food.

Finally, I would like to express my utmost gratitude to Christophe Masson, my partner and best friend. I am immensely grateful for his help and support, as well as for his kindness and critical intelligence. I thank him for reading many drafts and engaging in challenging discussions, for his patience and encouragement, and for his wonderful sense of humor, which brings happiness and gourmandise to my life every day.

Introduction

De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum?

One must not dispute about tastes. Everybody has his own taste.

Dictionnaire de lAcadmie franoise , s.v. Got

To each his own taste. What a powerful commonplace. Why should we even bother discussing a topic such as taste? The sense of taste seems too personal to be generalized; it is so instantaneous that this sensation seems to precede thoughts and language; it may seem trivial to the point that such an insignificant matter should not deserve our interest. Associated with a form of animal instinct, the sensation of taste is deeply incommunicable, affective, utterly intimate, and idiosyncratic. Why then, and how, can we investigate the history of the sense of taste? What is more ephemeral than a flavor, more indefinable than pleasure? Taste, like any other form of sensory experience, always seems somehow to slip away. Yet although the ineffable aspects of sensation necessarily escape historical investigation, the elusiveness of the senses does not mean these cannot be addressed. Silences and impalpable objects are also part of history.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.