First published in 2000 by

Routledge

29 West 35th Street

New York, NY 10001

Published in Great Britain in 2000 by

Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane

London EC4P 4EE

This edition published 2012 by Routledge

| Routledge | Routledge |

| Taylor & Francis Group | Taylor & Francis Group |

| 52 Vanderbilt Avenue | 2 Park Square, Milton Park |

| New York, NY 10017 | Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN |

Copyright 2000 by Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers.

We are grateful for permission to reprint revised versions of chapters 4, 7, and 9. A different version of chapter 4 was published as Writing, Politics, and las Lesberadas: Platicando con Gloria Anzalda in Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 14 (1993): 10530; a different version of chapter 7 was published as An Interview with Gloria Anzalda in Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies 14 (Spring 1995): 1222; and a different version of chapter 9 was published as Toward a Mestiza Rhetoric: Gloria Anzalda on Composition and Postcoloniality in JAC: A Journal of Composition Studies 18 (1998): 127.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

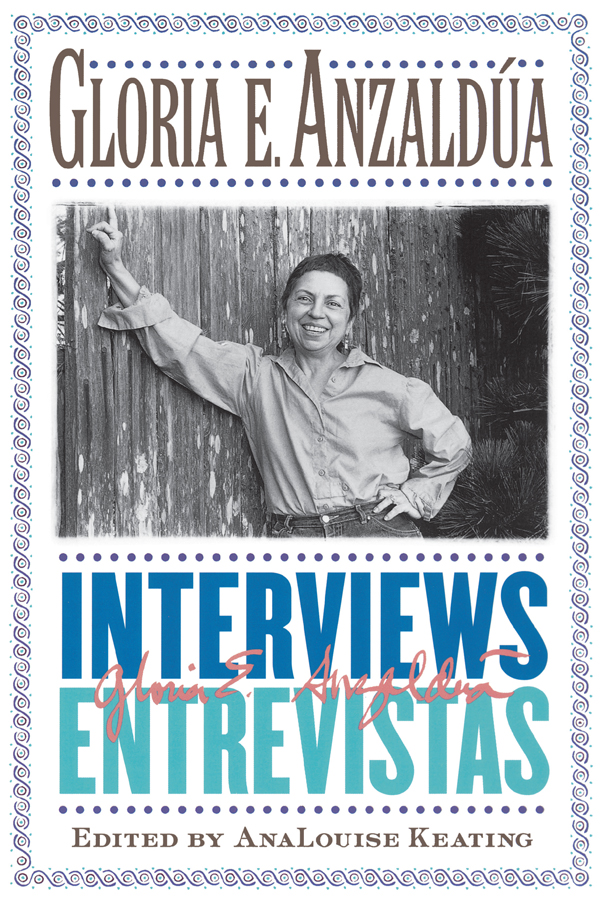

Anzalda, Gloria.

Interviews/Entrevistas / Gloria Anzalda ; edited by AnaLouise Keating.

p.cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0415925037 (hb) ISBN 0415925045 (pbk.)

1. Anzalda, GloriaInterviews. 2. Women and literatureUnited StatesHistory

20th century. 3. Authors, American20th centuryInterviews.

4. Mexican American lesbiansInterviews. 5. LesbiansUnited StatesInterviews. 6.

Mexican American authorsInterviews. 7. Mexican Americans in literature.

8. Lesbians in literature. I. Title: Entrevistas. II. Keating, AnaLouise, 1961 III. Title.

PS3551.N95 Z464 2000

818.5409dc21

[B]99055530

...............................

...............................

Interviews involve a tremendous amount of work. Before the actual interview, you must track down and contact the person whom you hope to interview and, assuming he or shes willing, arrange a time and place for the interview; you need to acquaint yourself as thoroughly as possible with the interviewees life and workreread her writings, look at what other scholars have said about her words, read other existing interviews, and so forth; you must then compose provocative questions designed to generate enriching dialogue that will enhance a readers knowledge of your interviewee; and you must obtain and test the necessary equipment (a high-quality tape recorder, additional microphones if possible, tapes, and so forth). During the interview, you must keep your attention closely focused on the conversation, listen carefully yet be ready to ask follow-up questions to further enrich the dialogue. (Dont get distracted, dont let your mind wander, think quickly and make connections between interviewees comments and her writings.) You also need to keep an eye on the recorder (is the tape still running? should you turn it over yet?) and make sure youre not overly exhausting your subject (does she seem tired? bored? distracted? should you cut some of the questions and wrap it up early?).

And the work isnt finished once the interview itself has taken place. You still need to transcribe the tape(s) (listening carefully to the tape, stopping after every sentence or two, rewinding to listen again to unclear words or phrases). When youve got the first draft of your transcription, you must proofread it carefully, checking the manuscript against the tape; you might need to contact your interviewee for clarification (accurately spelled places and names, missing dates, inaudible words, additional information, and so forth). This process takes much longer than the interview itself.

I know these details from my own work as an interviewer, and I want to thank the people whose words are collected in this volume for their time-staking work. Linda Smuckler, Christine Weiland, Jeffner Allen, Ins Hernndez-vila, Jamie Lee Evans, Debbie Blake, Carmen Abrego, Mara Henriques Betancor, and Andrea Lunsford: My thanks for completing the tasks described above; thanks for your support, for your interest in this project, for your willingness to share transcripts with me. Jeffner and Ins: Special thanks for taking the time to look over your conversations with Gloria. Debbie: A special thanks to you also for sending me copies of your interview.

I can only imagine the other side of the interview process. I dont know firsthand what its like to be interviewed, to be an interviewee. But I do know from conversations with Gloria and from the interviews Ive conducted with her that, while enjoyable, granting interviews takes a lot of effort. First, you must rearrange your own schedule (put aside writing projects, time with friends, the books youre reading, and so forth). Very possibly, the interview will become your work for the day. If your interviewer sent you questions in advance, youll probably look them over, think of possible responses, jot down some notes, and maybe do a little outside reading. When the person interviewing you arrives, you wont just dive into the interview and engage in a series of formal Questions and Answers. Instead, youll try to put your interviewer at ease, show her or him around the house, chat awhile, perhaps sharing intimate details of your life. Because you see interviews as a community-making ritual, youll try to get to know your interviewer, try to break down some of the barriers that so often inhibit effective communication. During the interview itself, you need to remain focused for several hours, listen carefully to the questions, and thinkquickly!of the best ways to respond. You might take a break from the interviewmaybe prepare some food and have a meal together, perhaps go for a walk. And then, refocusing your energies yet again, you go back to the interview. Its exhausting! And so, Gloria, I thank you for the time youve put into these interviewsnot only the original interviews included in this volume but also for the time youve spent on the interviews weve done together, for the time spent hunting down transcripts, looking for contact information, discussing the interviews with me, carefully reading the edited transcripts, making revisions to enrich your words. Thanks for reading my introduction twice and making very useful suggestions for changes; for your encouraging words; for being always available (even when the diabetes was acting up and you were clearly in pain, you answered my phone calls and talked at length); and for mentoring me through this process.

There are other people who have played important roles. Mi familia, of course: Thanks for your patience as I worked on this project, rushed to meet deadlines, spent time on the phone instead of with Jamitrice, and so on and so on. Margaret Estrada: Thanks for putting aside your other work and transcribing the interview tapes so quickly; this project would have been delayed for months without your assistance. Jesse Swan: Thanks for talking with me about the interviews and for offering your perspective on the interview process. Renae Bredin: Thanks for your encouragement. Aida Hurtado: Thanks for helping us contact Annie Valvo. Bill Germano, Amy Reading, Nick Syrett, and others at Routledge: Thanks for working with Gloria and me on this project; thanks for your useful suggestions; and thanks for your flexibility.