Copyright 2009 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

First published in German in 1936 as Die reitenden Geister der Toten

Copyright 1936 by Hans Alexander Winkler

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Dar el Kutub No. 16761/08

ISBN 978 161 797 259 1

Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Winkler, H.A.

Ghost Riders of Upper Egypt: A Study of Spirit Possession / Hans Alexander Winkler; translated by Nicholas S. Hopkins.Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008

p. cm.

ISBN 977 416 250 1

1. GhostsEgypt 2. GhostsSaidis I. Hopkins, Nicholas S. (trans.)

II. Title

398.250963

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 15 14 13 12 11 10 09

Designed by Andrea El-Akshar

Printed in Egypt

Introduction

Nicholas S. Hopkins

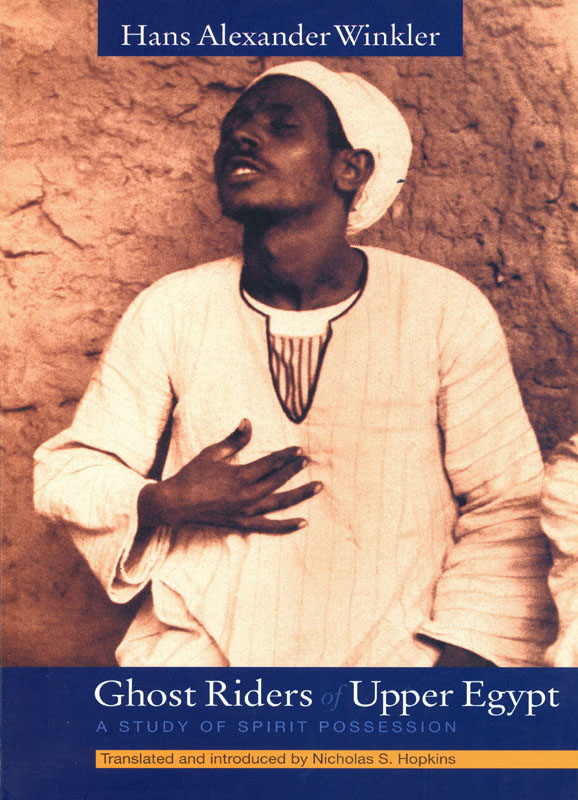

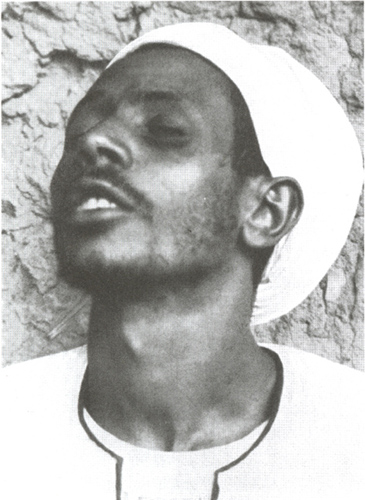

Ghost Riders of Upper Egypt is the translation of a book published in 1936 by the German anthropologist and specialist in comparative religion Hans Alexander Winkler. The expansive German title reads: Die reitenden Geister der Toten: Eine Studie ber die Besessenheit des Abd al-Radi und ber Gespenster und Dmonen, Heilige und Verzckte, Totenkult und Priestertum in einem obergyptischen Dorfe; in other words, Riding spirits of the dead: A study of the possession of Abd al-Radi and of ghosts and demons, saints and ecstatics, the cult of the dead and priesthood in an Upper Egyptian village. The imagery of the title refers to the notion that, in possession, the possessed is ridden by the possessing spirit, the way a rider rides his mount. In this case the rider is the ghost of a deceased member of society, and the mount is a living person, metaphorically a camel. The central figure in the study, Abd al-Radi, plays the role of camel to the ghost of his late uncle, Bakhit, who conveys messagesprophecies, diagnoses and cures, explanations of past events, and so onto those who come to Abd al-Radi. We would now say that he channels his late uncle. Or, in anthropological terminology, that he is a spirit medium.

Scholars have identified several ways in which spirits play a role in human society. Spirit mediumship is one such way, though not the only one. In spirit mediumship, the person possessed is considered an intermediary between this world and another, while spirit possession implies that an external spirit has taken over a body and is controlling it, perhaps causing it to behave in unusual ways (Firth 1964: 247). Of course, the two can blend into each other. In the zar possession cult, as described here and elsewhere in Egypt, the spirits may afflict a person, requiring a form of curing in which an accommodation between spirit and human is reached, allowing the human to live a normal life outside the ceremonies. Typically in these cases, the spirit is invited into the body periodically to placate the spirit and renew the relationship. Both spirit possession and spirit mediumship often involve a form of trance in which the persons normal personality is replaced by another. Such a trance in turn can be distinguished from one in which the personality is simply absent, and a sense of nothingness, perhaps felt as an identity with God, prevails. The anthropological and psychological literature on spirit mediumship and spirit possession is of course much richer, and more analytically sophisticated, now than it was in Winklers time, but Winklers material is consistent with most modern interpretations.

Abd al-Radi lived in the village of Naj al-Hijayri, near the town of Qift, situated between Luxor and Qena in the governorate of Qena. Qift goes back to pharaonic times, as the ruins attest. It was one of the termini in the Nile Valley for the trade routes leading across the desert to the Red Sea. Naj al-Hijayri was a relatively recent settlement near the edge of the desert to the east of Qift, and its inhabitants were distinguished from other villages nearby by being settled Bedouin rather than longtime farmers. In fact, there was little difference between these two groups other than a memory of a separate identity. Among other groups in the area were more recently settled Bedouin, the Azayza, and a community of Ababda. The origin of the Ababda is very contested, but they retain a sense of distinctiveness with respect to the Arabic-speaking groups; they are found in small groups throughout Upper Egypt. All these groups reflect the tendency of Bedouin to settle and become farmers, or to fill niches in agricultural society. All were joined together in certain social and cultural practices.

This multilayered study of the 1930s was precocious in its method and conclusions, and thus it retains its relevance today not only for Egyptian folklore but also for the history of anthropology in Egypt. In contrast to many other anthropological studies of that period, it is not just a list of details, but an effort to place a social process in cultural contextit is an extended case study. Winklers careful ethnography highlights the time and the place of interviews and possession episodes. He recounts not only the history of Abd al-Radi but that of several other figures who came into view in the setting around him, some of them perhaps competitors for public attention. Winkler stresses the social process whereby an initial experience of possession evolves into a new example of a familiar social formthe spirit medium as the link between this world and the yonder one, and the social structure that grows up to enable this. The practices described here both reflect village social organization and lead to changes within it.

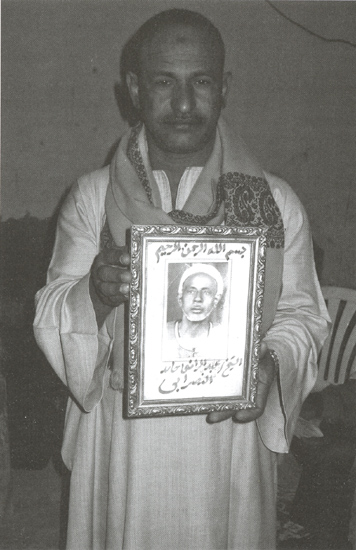

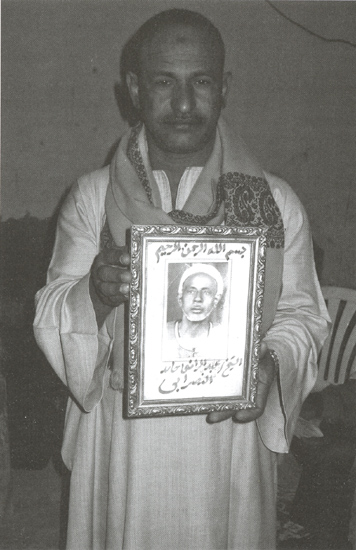

Abd al-Radis grandson displays a picture of his grandfather. Naj al-Hijayri, November 2006

Reem Saad

Winkler writes himself into the story, not only by recounting in the first person his interactions with Abd al-Radi and his entourage, but also by himself asking questions relating to his own family and life, so that he could evaluate the accuracy of the answers. Winkler details the growing personal relationship between himself and Abd al-Radi. Although there were enormous differences between the German scholar and the Egyptian farmer, there were also certain parallelscommon age and family circumstance, and a life history that included low-paid labor (Hopkins 2007). The depiction of the relationship between the researcher and the informant is one of the more original themes of this book.

Winkler sometimes refers to his interlocutor as Abd al-Radi, at other times as Bakhit, depending on his interpretation of the moment, as two distinct personalities successively occupy the same body. In fact, the spirit possession is more extensive, and the anthropologist shows how in fact multiple personalities appear in Abd al-Radi, although Bakhit remains the dominant one. He raises a possible interpretation in terms of Abd al-Radis split personality, but does not develop the point. The analyses of the different mental crises people suffer certainly also raise questions for psychological anthropology, but Winkler deliberately stays away from psychology.