Also available from Bloomsbury

UFOs, Conspiracy Theories and the New Age , David G. Robertson

Religion and Space , Lily Kong and Orlando Woods

Religious Objects in Museums , Crispin Paine

Museums of World Religions , Charles Orzech

Christian Tourist Attractions, Mythmaking, and Identity Formation , edited by Erin Roberts and Jennifer Eyl

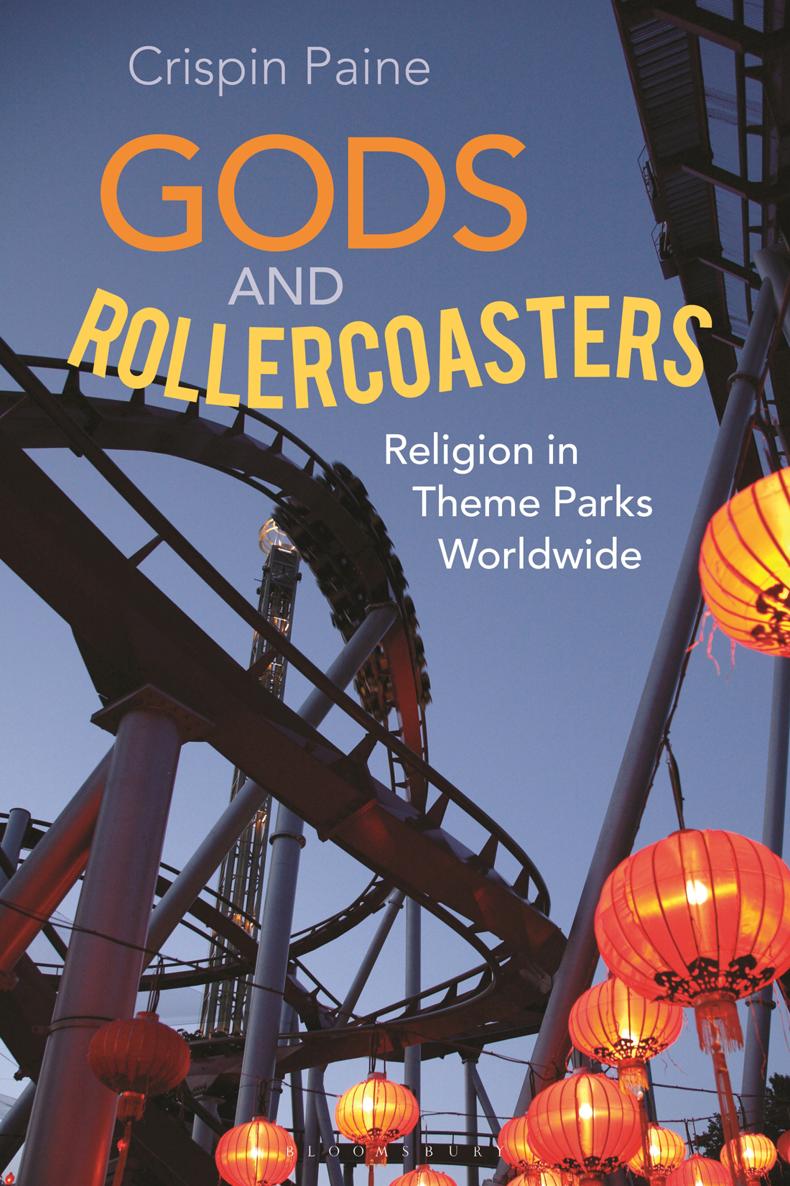

Until my wife told me it was just pretentious, I was planning to title this Preface Apologia pro Libro Suo, after Cardinal Newmans famous defence. I still feel that this small book needs an Apologia rather than a mere Preface. It has a number of problems. First, it seems to be the first book to address the subject. There is a large and fast-growing literature on theme parks, their nature, origins and role in contemporary society, as well as on their technical and business aspects; as one theme park researcher put it: Theme park research remains, as of yet, almost as dizzyingly heterogeneous as the parks themselves (Freitag 2018).

There is also of course a gigantic literature on religion, and on its new role in a globalizing and postmodern society and a much smaller literature on how people today do religion, especially outside traditional places of worship. But on religion in theme parks there is but a handful of books on Bible-based attractions in the Americas, on Buddhist attractions in Asia, and a further handful of books, papers and theses discussing individual parks on both continents. There seems to be nothing so far which tries to examine the phenomenon on a comparative basis worldwide; indeed, this books first task is to persuade the reader that there is a phenomenon to examine. So, this book can only be an introduction to the field, which hopefully may prompt others to give it much more profound attention.

Secondly, the author is seriously under-qualified to take on the task. I spent my career first as a working curator in local history museums in England, and later as a manager and adviser to small museums. To take on what should really be a big scholarly task could be seen as optimistic, to put it mildly. But having helped found the journal Material Religion in 2005 and having published or helped to publish three books on religion in museums, it seems natural to get interested in how religion happens in other leisure venues.

Thirdly, defining a religious theme park is challenging, if not impossible. They merge easily into pilgrimage sites and temples, open-air museums and heritage sites, festivals and camp meetings, dramas, and the kind of religious city found especially in Nigeria.parks are adopting aspects of religion, while in Asia temples are adopting aspects of theme parks.

Though I claim this is the first study of religion in theme parks worldwide, there are very valuable studies of a number of aspects of the subject. The literature on theme parks as such is of course substantial, from works that look at their history and nature, to introductions to their techniques, to theme parks as businesses. point up the value of analyses of religion parks and of their political and cultural role. Almost a religion park is Museum of the Bible in Washington DC, the subject of Candida Moss and Joel Badens Bible Nation . These books are supported by a few theses, notably Sara Callahans Where Christ Dies Daily: Performances of Faith at Orlandos Holy Land Experience and Terry Webbs Mormonism and Tourist Art in Hawaii .

A very different kind of study of a very different kind of visitor attraction is Sara Pattersons lovely essay Middle of Nowhere on a highly personal religious structure built by an outsider artist in the Californian desert. In addition, of course, there are a goodly number of shorter descriptions of individual parks, from Daniel Radoshs description of Heritage USA in Rapture Ready to Kavita Singhs study of Akshardham New Delhi, to Judith Schlehes study of Bukit Kasih . Much more common than religion parks as such are culture parks in which religion appears; Joy Hendry gives a generous amount of attention to religion in her stimulating account of culture parks in Japan, The Orient Strikes Back.

We start (Chapter 2) by looking at seven religion parks: Holy Land Experience in Orlando (Evangelical Christian), Haw Par Villa in Singapore (Daoist/Buddhist), the two Akshardhams in New Delhi and Gandhinagar (Hindu), Sui Tin Theme Park in Saigon (Buddhist), and two Creationist parks in the United States, the Creation Museum and Ark Encounter .

In Chapter 3 I argue that religious theme parks are the product of: huge social and economic changes in the world over the past two generations, including the vast new middle class with disposable leisure time; the interaction of religion with modern technology; the growth of prosperous sects with strong middle-class support; urbanization and globalization leading to nostalgia for traditional values; and the growth of tourism.

But why are they founded in the first place? The overt aims of religious theme parks include spreading the Word, associating faith with modernity and reaching leisured audiences. Chapters 4 and 5 suggest that their unavowed aims can include conservative politics in US Christian theme parks, Hindutva ideology in Hindu theme parks and, in many countries, the promotion of patriotism in the cause of national unity. Behind their creation can also lie the influence of their promoters personal faith, and the hugely important crossover with temples and pilgrimage sites.

Above all though, theme parks offer escape. In culture parks escape is to the exotic other: the exotic past or the exotic foreign, occasionally to the exotic future. Amusement parks offer escape into pure fantasy and fun. But religion appears in parks of all kinds, offering its own form of escape.