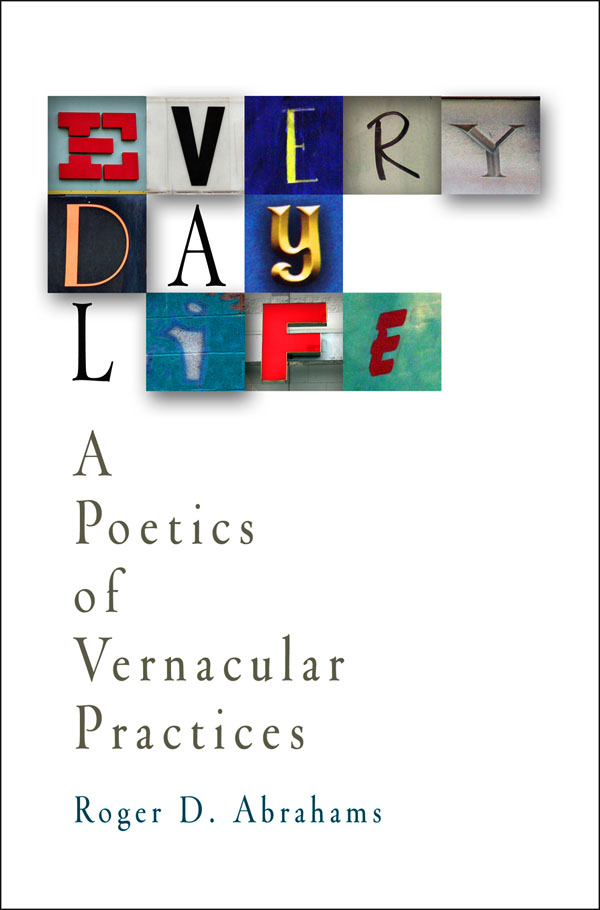

Copyright 2005 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Abrahams, Roger D.

Everyday life : a poetics of vernacular practices / Roger D. Abrahams.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-8122-3841-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. CultureSemiotic models. 2. Manners and customs. 3. Anthropological linguistics. I. Title.

GN357 .A27 2005

Introduction

A poetics of everyday life? Perhaps I mean a poeticizing of everyday practices, looking at vernacular culture as animated by our making and doing things with style. Our lives are replete with artifacts growing from our propensity to form groups through the creation of ways of speaking which give form to shared concerns and ideals. As Kenneth Burke has it, There are no forms of art which are not forms of experience outside of art (Burke 1931). But how do we sense, in common, when art is present, and use this state of being as a way of understanding our own cultural practices? The line between those practices which ask simply for our conscious attention and those which call for aesthetic or, at least, stylistic judgment can easily be confounded.

Richard Rorty describes this attempt to find whatever poetics there are in the vernacular and gives voice to its implicit assumptions.

A poeticized culture would be one which would not insist that we find the real wall behind the painted one, the real touchstones of truth as opposed to touchstones which are merely cultural artifacts. It would be a culture which, precisely by appreciating that all touchstones are artifacts, would take as its goal the creation of ever more various and multicolored artifacts. (Rorty 1989: 5354)

We look for meanings, not behind our vernacular artifacts and interactions, but in them.

Edward Sapir, a poet as well as pioneer linguist, asserted that language itself constituted the most significant and colossal work that the human spirit has evolvednothing short of a finished form of expression for all communicable experience. Extolling its capacity to constantly reshape itself, he continues: Language is the most massive and inclusive art we know, a mountainous and anonymous work of unconscious generations (Sapir 1921: 220). Yet, as any writer will attest, language yields up its artful power only grudgingly. For there are other selves with whom we hold constant conversations, selves who speak in tongues not entirely under anyones personal control except the phantoms of these unconscious generations. Studying other cultures from the perspective of our Western, Anglophonic tongue, we seek to familiarize ourselves with their keywords for life and art. Our own vernacular speech will bear up under such scrutiny as well.

This address to vernacular culture may appear as an abomination to those not enamored of the near, the low, the common, as Ralph Waldo Emerson put it in The American Scholar: the meal in the firkin, the milk in the pan; the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the glance of the eye; the form and the gait of the body. Emerson, like many speakers in the early American republic, saw New World vigor in the juxtaposition of the highest and the most common registers of the vernacular. The poetics of the vernacular begins with the ability of speakers to command the widest variety of ways of speaking, soaring high and digging deep with an understanding of the dynamic contrasts this code-switching animates. If freedom lies in the ability to make choices, dealing with vernacular life allows the whole ideal to be expressed within a single sentence, or represented in a representative object.

Keeping Company

This book considers the ways in which ordinary Americans keep company with one another, in casual and serious talk, at play, and in performance and celebration. It explores the entire range of social gatherings, from chance encounters and casual conversations to the heavily rehearsed shows found at theaters and stadiums, or in the more open venues of parades and festivals. It focuses not just on the ways we pull off our interactions, stylized or otherwise, but also on the vernacular terms we have developed in common to discuss and judge performances.

Central to this understanding is the presumption of goodwill that we make about how others will treat us. We presume that our gregariousness reveals a useful excess of feeling and that having a good talk is a palliative for any misunderstandings that arise. We have learned from experience that this friendliness is not necessarily shared; unfounded assumptions about our cultural commonalities can lead to social and political complications, especially in times of declared animosity. But the social compact is constituted by our talking with one another. With strangers and acquaintances alike, we act on the useful fiction that talking it out will lead to mutual understanding and the possibility of shared enjoyment. So this book explores not just our comfortable interactions with family and friends and the assumptions that underlie intimate acquaintance but also our navet and the high premium we pay for presuming the palliative powers of having a good talk, even an argument we can then talk through.

Although friendly conversation seems natural, it is, in fact, deeply cultural, providing a moral center for everyday communication. Certain terms of judgment underlie our discussions of the everyday. The appropriateness of what we say and do is often debated; an action may be judged playful by some and offensive by others. How studied should one be, and how do we judge going through the formalities? The degree of self-conscious agreement that we feel impelled to uphold is itself revealing of the tensions that swarm beneath the surface of our interactions. Equally important for the purposes of this book, conversation conducted under the sign of friendliness provides a baseline against which other ways of speaking may be judged. Consider the implications of the ubiquitous idea that when people sit down and talk together, our common human concerns can be relied upon to encourage agreement. Even if disagreement enters this terrain, it can fuel the sense of achievement when, at last, consensus is reached.

This analysis of expressive interaction starts with the commonsense view that we are our own best interpreters and addresses the entire range of communicative acts through the terms we use to describe them ourselves. The rich resources of our everyday vernacular speech enable us to use words and gestures from the past as models for social interaction in the present. As a folklorist, I have catalogued the conversational repertoire we have inherited from our elders and forebears that we presume ties us together morally and serves to repair relationships. In the simple forms of vernacular expression, the proverbs we invoke and the jokes we tell, we see the elementary tactics of using the past to resolve problems in the present. These memorable, fixed phrases come to mind habitually, but they are far from simple when we attend to how they are deployed in daily interaction.