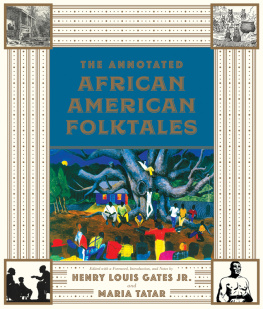

Also by Roger D. Abrahams

African Folktales

Singing the Master: The Emergence of African American Culture in the Plantation South

Copyright 1985 by Roger D. Abrahams

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published as Afro-American Folktales by Pantheon Books in 1985.

Since this copyright page cannot accommodate all permissions acknowledgments, they appear on .

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

African American folktales : stories from black traditions in the new world/selected and edited by Roger D. Abrahams.

p. cm.

Originally published: Afro-American folktales. 1985. (Pantheon fairy tale and folklore library). Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-80318-4

1. Afro-AmericansFolklore. 2. TalesUnited States. 3. BlacksCaribbeanFolklore. 4. TalesCaribbean. I. Abrahams, Roger D. II. Title. III. Series: Pantheon fairy tale and folklore library.

GR111.A47A38 1999 398.208996073dc21 98-42200

v3.1

To the great scholar-warriors in

the Transatlantic campaign,

William A. Bascom and Richard M. Dorson

Now you are going to hear lies above suspicion.

Zora Neale Hurston

PREFACE

T hese tales have come from many parts of the New World where Afro-American communities were established during plantation times or after emancipation in the nineteenth century. I have included stories from throughout the huge area where plantations were worked, from coastal South and Central America to the Caribbean and, of course, the American South. Although most of the communities from which the stories were collected are within the English-speaking sphere of influencewhere an anglophonic Creole is spokenI have not resisted dipping into the rich patois of Haiti, Guadaloupe, and Louisiana whenever I found representative materials that had already been translated into English.

A few texts are taken from early travel reports and plantation journals the oldest is from 1815but most come from documents produced when the most extensive collecting was carried out, beginning in 1881 with the first of Joel Chandler Harriss Uncle Remus collections and proceeding through the 1920s. For more contemporary texts, I have used mostly materials that I recorded in the United States and the Caribbean. In almost all cases, the titles to the stories are my inventions, my attempt to give the reader a hint about the subject and tone of the story to come.

A number of Afro-Americans have collected these stories, but most collecting has been carried out by whites. In retrospect, this does not seem as important as the fact that, with the exception of Zora Neale Hurstons great book Mules and Men and a very few others, tale gathering was carried out by individuals who did not live in the communities in which the tales had been maintained. Today, the major differences in quality seem to arise from whether the tales were collected as they were usually performed, by collectors doing their recording as part of a documentation of group life, or by those who were just passing through, trying to get as many stories and songs and riddles as possible in whatever time they had been able to give to their fieldwork.

Following the Harris tradition of rendering tales in dialect, not only through the use of vernacular forms of speech but also by making orthographic modifications of standard English spellings and diacritical markings, most of the collections culled from were originally printed in a style that the contemporary reader would find difficult to read. Moreover, such texts are replete with reminders of the ugliest side of stereotyping. There are thus two very good reasons for making the changes in language and tone that the reader will encounter herein.

In the hands of some collectors, including Harris, the spelling and the cadences of the vernacular used in these early gatherings add up to an honest and reasonable attempt to record local speech variations. But the retellings of the tales by Harris and his followers gave them a kind of literary shape and finish that are never found in actual oral renditions. This serves up to us stories told from beginning to end, and without the repetitions, mistakes, and hesitations that characterize oral tellings; it does not record the performance as accurately as one finds in most collections that come from folklorists who have had the benefit of tape-recorded and transcribed texts. Moreover, we simply cannot get beyond the racist resonances that the Uncle Remus-style tellings continue to carry, precisely because the stories are rendered in the dialects of slavery times. I have attempted to take some of this stigma away by using contemporary spellings, and by changing some of the vernacular turns of phrase that would have been familiar to the nineteenth-century reader but that have lost their currencyand thus their pungencytoday.

In one regard, however, the Harris style does reflect the storytelling context nicely. He presents the stories as told to a group of young children, thus providing a setting for the tales and personalizing them. He puts them in the mouths of storytellers who may be interrupted, questioned, asked to apply the tales to local situations and happenings. In such reminiscences we still do not have versions of the tales as told by blacks to one another in a regular and familiar setting. This point is significant, for in such situations the narrator can assume that nearly everybody knows the stories and therefore need not follow the rule that they must be told from beginning to end. The version we are given always assumes that the fictional hearer has not heard the story before.

The dialect itself commonly draws, willy-nilly, from a lingua franca that had developed along coastal Africa; it had a Portuguese as well as local African vocabulary, and with a sound system and grammar developed in this Old World trade setting. Thus, when they came to the New World, the slaves already had a means of communication that transcended the problems of forging a community from so many different cultural and linguistic groups in the Old World. Once in the New World, the speakers of this West African Creole began to draw strongly on the vocabulary of the Europeans who had brought them to the New World, and even more, on the language of the plantocrats. Thus we find in areas colonized by France a francophonic Creole or patois, such as that spoken in Haiti, Martinique, and some places in Louisiana; Papiamentu, spoken in Curacao and Aruba and other Dutch possessions and using vocabulary from Spanish, Portuguese, and English as well as Dutch; and English Creole of various sorts, the best known being Gullah in the Sea Islands off South Carolina and Georgia and Jamaican Creole. Most of the stories in this book were recorded in one or another Creole. To most non-Creole-speaking readers, these renderings in their original form are at best extremely difficult to understand.

Making it even more difficult for readers, jocular storytelling may be judged by how quickly and fluently the talk of the characters can be rendered and how many ranges of voice the taleteller can draw upon. The trickster himself is often portrayed as having a lisp; other animal characters have their own characteristic way of producing their talk, so that a master storyteller may scream, laugh, shout, rasp, whisper, and imitate in some equally stretched manner the way an animal, devil, witch, or ghost might talk.