HOW TO REALIZE

EMPTINESS

HOW TO REALIZE

EMPTINESS

by

Gen Lamrimpa

(Lobsang Jampal Tenzin)

Translated by

B. Alan Wallace

Edited by

Ellen Posman

Snow Lion Publications

Ithaca, New York

Snow Lion Publications

P.O. Box 6483

Ithaca, New York 14851 U.S.A.

607-273-8519

www.snowlionpub.com

Copyright 1999, 2010 B. Alan Wallace and Gen Lamrimpa

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced by any means without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-55939-358-4

Printed in the USA on acid-free recycled paper

The Library of Congress cataloged the previous edition of this work as follows:

Gen Lamrimpa, 1934

Realizing emptiness : the Madhyamaka cultivation of insight / Gen Lamrimpa (Lobsang Jampal Tenzin) ; translated by B. Alan Wallace ; edited by Ellen Posman.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-55939-118-9

1. Sunyata. 2. MeditationMadhyamika (Buddhism) 3. Vipasyana

(Buddhism) I. Wallace, B. Alan. II. Posman, Ellen. III. Title.

BQ7457.G46 1999

294.34435dc21

99-31832

CIP

Foreword

In January 1989, after leading a one-year retreat for the cultivation of meditative quiescence in the state of Washington, Gen Lamrimpa was asked by his students to give practical instructions on the cultivation of insight into the nature of emptiness. The following teachings are a record of those lectures, which were transcribed by and originally edited by Gen Lamrimpas devoted student Pauly Fitze. At my request, the major work of editing was later done by Ellen Posman, who joined two versions of Gen Lamrimpas narrated biography, one of them originally written down by Steven Wilhelm, into the version presented in this volume. For their invaluable contribution, I offer them my deep thanks.

After the retreat, Gen Lamrimpa also presented two lectures, one at Stanford University on the Madhyamaka view, and the other at the San Francisco Zen Center on Dzogchen. These are included here as appendices.

I was the interpreter for all the above teachings, and I have done the final editing of all these lectures, so any errors that may appear in this version are entirely my own. All of us who have worked to make these experiential teachings available to those who did not have the fortune to receive them directly from Gen Lamrimpa himself pray that this book may be of benefit to all sentient beings.

A Contented Mind:

The Life of Gen Lamrimpa

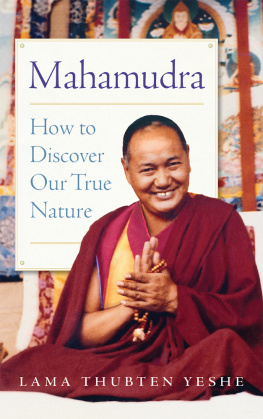

The Venerable Jampal Tenzin, Gen Lamrimpa, teaches that a contented mind is within our grasp, no matter how difficult the conditions of our lives. Genla, as he is affectionately called by his students, is one of the small number of Tibetan monks who spend most of their time in solitary meditation. He makes his home in a forest hut in Sikkim, where he lives simply and engages in spiritual practices.

A visitor to the small apartment where Genla stayed during a three-month visit to Seattle was struck by the way his peaceful mind had transformed his room into a facsimile of his mountain hut. When he was not meditating or taking visitors, he would sit by the window, wrapped in a robe, studying one of the Tibetan religious texts he brought with him. Happiness depends on the mind, Genla says, his kind, twinkling eyes looking intently at the visitor. If we work on this, increasing he positive mind and reducing the negative mind, then we can achieve ultimate peace. But if Genlas state of mind is the embodiment of his teachings, it is not because he has led a protected or insular lifein fact, he has lived through tumult and tragedy.

Born Lobsang Jampal Tenzin in 1936 in the western Tibetan town of Shekar, in the Tingri region, Genla was groomed for the monastic life from the start. In Tibet, there are two traditions that dictate how and when one becomes a monk or a nun. The first custom is for a boy or girl to make his or her own decision after he or she has grown up. The other tradition says that when there are two boys in a family, one of them should become a monk. In accordance with this latter tradition, Genla became a novice monk at the age of seven. His father looked for a good lama at Chusang Monastery, and Lobsang Sangye became his spiritual mentor. Genla received teachings from him and received full ordination as a monk of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism at the age of thirteen. He was given the name Lobsang Jampal Tenzin.

When Genla became a monk, he was very happy about the decision. Even as a little boy he remembers playing and sitting on a throne like a lama, with children sitting around him receiving teachings. At that time he was called Lama-la, and some people regarded him as tulku , or incarnate lama. Even adults would come to ask him questions, and he remembers saying strange things at times. Still, he does not remember now whether or not he remembered any past lives at that time.

Genla remembers his years at the monastery as a happy time of study and prayer. Once I entered the monastery, he says, I learned to read the scriptures, to read them very quickly in fact, and I memorized many root texts. I also learned to perform all the various rituals, make the ritual cakes for the prayers, and play the big temple horn. Since deep study was not very common in the small monasteries in Tibet back then, I learned these other things. At that time, he notes, I didnt understand the true meaning of Dharma, particularly the purpose or reason of Dharma, and he says that he did not really comprehend the texts he was so skilled at memorizing. Like many young Tibetan males, he had been swept into his life as a monk by tradition, like grass carried along by a river, he says.

Besides remembering this as a time of study, Genla also fondly remembers his days of mischief. At one point, a time of internal conflict at the monastery led to a lack of discipline; as a result he and some of his friends would run away from the monastery in the evenings to play dice, and would sometimes stay out all night. The next morning, exhausted, he would throw his robe over his head during prayers and doze off. When the prayers were over and everyone had left, Genla recalls with a chuckle, he would still be sitting there wrapped in his robe, fast asleep.

Later, he was put in charge of the food and the kitchen, a responsibility he performed for about two years. Then he asked his abbot to release him from that work in order to have time for study, and he also told his father that he wanted to go to Lhasa for further education. However, those first years of Genlas adulthood were dark ones, as the Chinese communists gradually tightened their control over Tibetan society. By 1959 the noose had closed, and Genlas monastery was seized by the Chinese. Genla was declared a counter-revolutionary, and the Chinese authorities ordered his capture.

Knowing His Holiness the Dalai Lama had already left Tibet, Genla resolved to flee also. Unable to even return to his room at the monastery for fear of being captured, he left all of his possessions behind and journeyed on foot with his parents over the mountains to Nepal. Genla arrived in Nepal penniless, with his shoes rotting on his feet from the monsoon rains. His mother died within the next year, and Genla found himself torn with doubts about the Dharma. I was really struggling about whether there was any such thing as Dharma, he recalls, and says he had deep qualms about the validity of karma: the idea that virtuous actions bring forth happiness, and nonvirtuous actions bring unhappiness. During those many years he did a lot of contemplation and analytical meditation. After some time he came to the conclusion that the reasons supporting the relationships between good actions and happiness, and bad actions and unhappiness, proved valid, and he was able to recognize his doubts as invalid. So despite his circumstances, Genla continued his practices.