This book contains Divine Names.

Do not take it into the bathroom or any other unclean place.

First published in 1982 by

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

With offices at

500 Third Street, Suite 230

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.redwheelweiser.com

First paperback edition, 1985

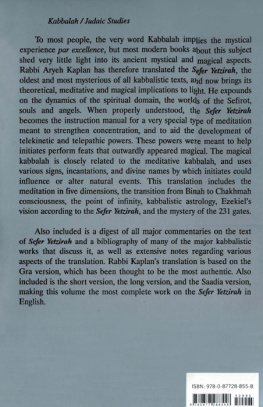

Copyright 1982 Aryeh Kaplan

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-70150

ISBN-10: 0-87728-616-7

1SBN-13: 978-0-87728-616-5

Cover design by Bima Stagg

Printed in the United States of America

MG

20 19 18 17 16 15

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

Contents

With trepidation and love...

By authority from my masters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Perle Epstein.

Library of Jewish Theological Seminary of America, New York, New York, particularly to Ms. Susan Young and Mr. Micha Falk Oppenheim.

Hebrew University Libraries, Jerusalem.

Bodleian Library, Oxford, England.

Biblioteque Nationale, Paris, France.

British Museum, London, England.

Biblioteca Apostolica Vatican, Vatican City.

Columbia University Library, Manuscript Division, New York, New York.

Lenin State Library, Guenzburg Collection, Moscow.

Introduction

It is with great trepidation that one begins to write a work such as this, involving some of the most hidden mysteries of the Kabbalah. Many would question the wisdom and propriety of placing such information in a printed book, especially in an English translation. But so much misinformation has already been published that it is virtually imperative that an authentic, authoritative account be published. It is for this reason, as well as other reasons which I am bound by an oath to conceal, that the great living masters of Kabbalah have voiced their approval that such a book be published.

The science of Kabbalah is divided into three basic areas: the theoretical, the meditative, and the practical.

The theoretical deals with the form of the mysteries, teaching the structure of the angelic domains as well as of the Sefirot, or Divine Emanations. With great success, it deals with problems posed by the many schools of philosophy, and it provides a conceptual framework into which all theological ideas can be fitted. More important for the discussion at hand, it also provides a framework through which the mechanism of both the meditative and practical Kabbalah can be understood.

Some three thousand Kabbalah texts exist in print, and, for the most part, the vast majority deal with the theoretical Kabbalah. Falling within this category are the best known Kabbalah works, such as the Zohar and the Bahir, which are almost totally theoretical in their scope. The same is true of the writings of Rabbi Isaac Luria, the Ari, considered by many to have been the greatest of all Kabbalists. With the passage of time, this school probed deeper and deeper into the philosophical ramifications of the primary Kabbalistic concepts, producing an extremely profound, self-consistent and satisfying philosophical system.

The practical Kabbalah, on the other hand, was a kind of white magic, dealing with the use of techniques that could evoke supernatural powers. It involved the use of divine names and incantations, amulets and talismans, as well as chiromancy, physiognomy and astrology. Many theoretical Kabbalists, led by the Ari, frowned on the use of such techniques, labeling them as dangerous and spiritually demeaning. As a result, only a very small number of texts have survived at all, mostly in manuscript form, and only a handful of the most innocuous of these have been published.

It is significant to note that a number of techniques alluded to in these fragments also appear to have been preserved among the non-Jewish school of magic in Europe. The relationship between the practical Kabbalah and these magical schools would constitute an interesting area of study.

The meditative Kabbalah stands between these two extremes. Some of the earliest meditative methods border on the practical Kabbalah, and their use is discouraged by the latter masters, especially those of the Ari's school. Within this category are the few surviving texts from the Talmudic period. The same is true of the teachings of the Thirteenth Century master, Rabbi Abraham Abulafia, whose meditative works have never been printed and survive only in manuscript.

Most telling is a statement at the end of Shaarey Kedushah (Gates of Holiness), which is essentially a meditative manual. The most important and explicit part of this text is the fourth section, which actually provides instructions in meditation. When this book was first printed in 1715, the publisher omitted this last, most important section, with the following note:

The printer declares that this fourth section is not to be copied or printed since it consists entirely of divine names, permutations and concealed mysteries, and it is not proper to bring them on the altar of the printing press.

Actually, upon examining this section, we find that divine names and permutations play a relatively small role, and could easily have been omitted. But besides this, the section in question also presents explicit instructions for the various techniques of Kabbalah meditation, and even this was considered too secret a doctrine to be published for the masses.

The Ari himself also made use of a system of meditation involving Yechudim (unifications), and this was included in the main body of his writings, particularly in the Shaar Ruach HaKodesh (Gate of the Holy Spirit). But even here, it is significant to note that, although the Ari lived in the Sixteenth Century, this text was not printed until 1863. For over three hundred years, it was available only in manuscript.

With the spread of the Hasidic movement in the Eighteenth Century, a number of meditative techniques became more popular, especially those centered around the formal prayer service. This reached its zenith in the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (17721810), who discusses meditation in considerable length. He developed a system that could be used by the masses, and it was primarily for this reason that Rabbi Nachman's teachings met with much harsh opposition.

One of the problems in discussing meditation, either in Hebrew or in English, is the fact that there exists only a very limited vocabulary with which to express the various technical terms. For the sake of clarity, a number of such terms, such as mantra and mandala have been borrowed from the various meditative systems of the East. This is not meant in any way to imply that there is any connection or relationship between these systems and the Kabbalah. Terms such as these are used only because there are no Western equivalents. Since they are familiar to most contemporary readers, they have the advantage of making the text more readily understood.

Next page