Table of Contents

FOR JUDITH

AND IN MEMORY OF GILES

preface

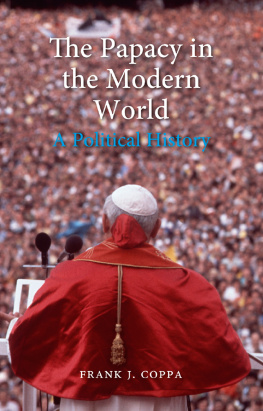

Trying to describe the entire history of the papacy, an institution that has survived for nearly two thousand years, in a single volume, is probably far too ambitious an undertaking. The most substantial treatment of the subject is the thirty-volume work of Ludwig Pastor, which confined itself to the period from the late fifteenth century to the end of the eighteenth, and still failed to be comprehensive. Several lifetimes of study would be needed to master the voluminous archives of the Vatican alone. Yet even in as small a scale as that offered here, it is a worthwhile undertaking. Few if any other human institutions have survived so long and played so continuously important a role not just in the history and affairs of Europe but also of the wider world. The papacys significance in modern times has been enormous, but it has not always had the character or exerted the influence we are familiar with today. Its story is a long and complicated one, full of incident, ideas and the interplay of personalities.

In attempting such a daunting task, I am enormously grateful for help and inspiration from many quarters. Stuart Proffitt first suggested to me the idea of a single-volume history, which was pursued with characteristic enthusiasmand many humorous emailsby my agent, the incomparable Giles Gordon. Following Giless untimely death I was extremely fortunate to be taken under the wing of John Saddler and now of Peter Robinson, both of whom set their seals on the project in subsequent stages, as did George Lucas in New York. Thanks are also due in many other directions, not least to Paul Harcourt and Jonathan Reilly of Maggs Brothers, who alerted me to the existence of several arcane books and manuscripts on papal history. I have been privileged to have my book pruned and greatly improved over the course of several months by the editorial skills of Norman MacAfee, while Lara Heimert at Basic Books and Ben Buchan at Weidenfeld & Nicolson have exercised benevolent oversight throughout. Walter Ficoncini and everyone at the Palazzo al Velabro made staying and working in Rome even more of a delight than it would normally be. Libraries, from those of the Vatican and the Ecole Franaise in Rome to New College and the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh, have provided generous access to their collections. I am most grateful to the School of History, Classics and Archaeology in the University of Edinburgh for the Fellowship during whose tenure this book has been both researched and written. The true inspirer, guide and constant companion of both the book and its author has been my wife, Judith McClure, to whom it is dedicated.

Roger Collins

The Isle of Eriska

January 2009

chapter 1

BISHOP OF ROME (c. AD 30-180)

A STORY OF BONES

One evening in early 1942, in Rome, after the great basilica of St. Peters had closed its doors for the night, the man in charge of the building, Monsignor Ludwig Kaas, descended into the archaeological excavations beneath it. With him was the foreman of the Vatican workforce carrying out the dig, Giovanni Segoni, who was keeping Kaas informed of everything the excavators were doing. This included their recent uncovering, just beneath St. Peters sixteenth-century high altar, of a small wall, one side of which was covered with roughly carved inscriptions and graffiti.

The archaeologists and excavation team had gone for the day. The two men were alone. And now Segoni showed Kaas an even more recent discovery. Within the little wall, the team had found a small concealed rectangular space lined with marble. In it were bones, which the archaeologists had not yet had time to examine, let alone record. Kaas told Segoni to remove and carry them as they returned to the surface.

The dig had begun after a discovery made in February 1939, when a tomb was being prepared for his predecessor, Pius XI (1922-1939), in the grotto underneath St. Peters, long the site of papal burials. In the course of that work a Roman cemetery, dating to the first and second centuries AD, had been found beneath the grotto. Originally this cemetery had been on ground level and consisted of streets of tombs that looked like little houses and were owned by wealthy families. The area in which it stood had been buried when a small hill was flattened during the construction of the earliest church on the site, which was built in the mid-fourth century over what was long believed to be the burial place of St. Peter.

The presence of St. Peter in Rome, his role in the founding of the Church in the city and his martyrdom and burial there had for centuries been the subject of often heated debate between Protestants and Catholics. Excavation of a site linked to Peters tomb, but whose results could not be predicted, could strengthen or weaken not just scholarly arguments but also the faith of hundreds of millions of believers. And so the Vatican decided that the dig should be carried out in complete secrecy, with nothing being announced until the results had been carefully reviewed. Although at first forbidden to approach the area immediately under the high altar, the excavations soon began to produce more and more intriguing results the closer they came to it, and in 1941 an extension was permitted to allow inclusion of this, the most sensitive part of the site.

As well as having the potential for theological fallout, the excavations had to be watched for any threat they might pose to the stability of the enormous church below which they were burrowing. For both reasons, while directed on a daily basis by scholars trained in archaeology and epigraphy, the study of inscriptions, overall charge resided with Monsignor Kaas. His own training and experience as a priest, a professor of canon law and a politician were very different from those of the archaeologists whose work he now had to monitor. Although he never himself explained why he ordered the removal and concealment of the bones, he apparently had little sympathy with archaeologists, whom, he felt, rarely treated human remains with proper respect. In any case these bones mattered less at the time than some others that had been discovered nearby a few weeks earlier. To that other set of bones we now briefly turn.

In 1941, when digging was extended to the area below the high altar, a red painted wall was found that had probably once formed part of a small open enclosure at the back of a street of Roman house-tombs. The archaeologists hypothesised that onto this wall a narrow stone table had been built supported on two legs at the front and with a small stone roof over it. It was located immediately below what became the altar of the first Church of St. Peters, and above which now stands the present sixteenth-century high altar. The assumption seemed irresistible that the place marked by this small stone table, which the archaeologists dated to the later second century, had been specially revered by successive generations of Christians.