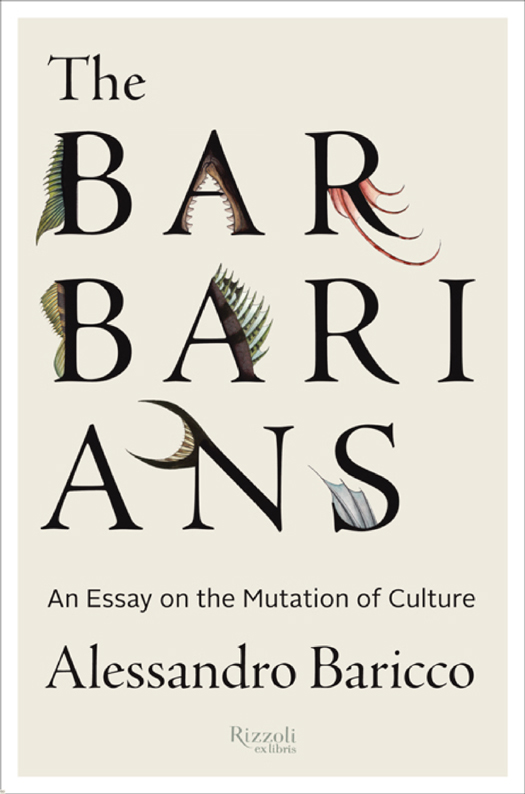

ALSO BY ALESSANDRO BARICCO

Emmaus

Novecento

An Iliad

Without Blood

City

Ocean Sea

Silk

PRAISE FOR ALESSANDRO BARICCO

Alessandro Baricco is a novelist who weaves words into a fabric as delicate as Venetian lace. His approach to prose is musical, sensitive to the melody of a sentence and the rhythm of a paragraph.

Chicago Tribune

PRAISE FOREMMAUS

Emmaus operates at such high intensity that all three times I set the book downtwice to make coffee, once to eat a small lunchmy eyes took minutes to readjust, so flat and muddy and standard definition did the world around me appear by comparison.

Adam Levin, author of Hot Pink and The Instructions

PRAISE FORSILK

Silk has the brilliant colors and the enchantment of a miniature. Vividly erotic.

Newsday

A riveting, lyrical love story, an accomplished historical fiction, a compact, condensed epic about human hearts in crisis.

Alan Cheuse, All Things Considered

First published in hardcover in the United States of America in 2013

by Rizzoli Ex Libris, an imprint of

Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

300 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10010

www.rizzoliusa.com

Originally published in Italian as I Barbari

Copyright 2006 by Alessandro Baricco

English Translation Copyright 2013 by Stephen Sartarelli

This ebook edition 2013 by Alessandro Baricco

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8478-4296-4

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8478-4296-4

v3.1

The fear of being overrun and destroyed by barbarian hordes is as old as the history of civilized culture itself. Images of desertificationof gardens ransacked by nomads, and of decrepit palaces in which goatherds tend their flockshave haunted the literature of decadence from antiquity to the present day.

WOLFGANG SCHIVELBUSCH , The Culture of Defeat

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION

I WROTE THIS book in 2006, in installments. Every five or six days I published a chapter in La Repubblica, the Italian daily I write for. I was writing live, so to speak, in the sense that when each installment came out, I still hadnt written the subsequent one, and so the comments I would find still fresh on the Web, and the reactions of my friends, relatives, and neighbors, could change my mind, and therefore the book, with every day that passed. Its a strange way to write a book. It was as though in order to study dolphins I had decided to live like a dolphin. At any rate, I remember that it came to me rather naturally.

Even as I was writing the installments, The Barbarians already prompted a lot of discussions and arguments, and these only increased later, when the essay was published as a single volume. Apparently it touched upon something dear to the hearts of everyone that seemed to require urgent attention: the impression that the planet was lurching toward a sort of cultural apocalypse, a spectacular descent into a new barbarism. The unease, if not the horror, at this sort of phenomenon was such that it took me a little while to make it clear that my book was not denouncing the new barbarians. I often had to explain patiently that, on the contrary, I had written the book in order to understand the barbarians, with the suspicion that, deep down, they might be right. And when I would say this, often my interlocutor (usually an intellectual or journalist) would react with deep dismay and astonishmentas if I had just stolen his or her Christmas presents. What I had taken from them, in effect, was a facile cause for indignation and disdain, and it was clear that this fact didnt sit well with them at all. But one thing Im proud of is that there are a great many people who, after reading The Barbarians, were forced to realize that they wouldnt be able to get away anymore with the usual preaching to the young who dont read, who eat fast food, and who dont know who Michelangelo Antonioni was. Before scorning what was happening, they would at least have to sweat a little.

Given the fact that publishing houses, too, are often strongholds of the (sublime) civilization that the barbarians are (rightly) transforming, I have had more than a little difficulty getting this book translated. It must be an unconscious form of self-defense. Or else Im overrating the quality of the book. I dont know. The fact remains, for example, that I have never found a publisher who wanted to have the book translated into English. Not that the Americans and the English are particularly interested in what we do in the far reaches of the Empire, in this lovely country of ours called Italy. Still, it irked me that the English-language audience couldnt read a book that concerned themas it concerned any other citizen of the planet, of coursebut concerned them above all, as masters of the planet. And so I did something I never do. I became determined, and for years I sought a way to bring The Barbarians to the very places where it apparently was not wanted. I was at the point of resigning myself to doing what I think is one of the most depressing things in the worldthat is, self-publishing it as an e-bookwhen I happened to mention the problem to Oscar Farinetti. Farinetti is not a publisher, let alone an intellectual. He is simply the most ingenious businessman I have ever met. And one of the most enthusiastic readers of The Barbarians that I have ever met. When I told him that the book did not exist in English, he said, I dont believe it. I swear its true, I said. All right, then, he said, well do it ourselves. By we he meant himself, me, and Eataly, his latest invention, a store in New York that has become one of the five most popular attractions in the city. Then we moved on to other subjects. But a year later, here we are, with The Barbarians. Try telling me this is not a peerless man. Try telling me not to dedicate to him, my friend and teacher in so many things, this English edition of my book.

One last note. Eight years have passed since I wrote The Barbarians. An eternity for a book that speaks of the present while trying to intuit the future. For example, when I was writing it, Twitter didnt even exist yet (it was born right around that time, to be precise). I have not, however, taken the trouble to correct mistakes, or update examples, or add any chapters on the latest developments. I would like people to read it as a book written in 2006, with the advantage of knowing how many things have turned out since. I would certainly have corrected it had I found that it had aged too much. But I remain convinced that, in its main tenets, the book still revolves very closely around what is happening across our planet.

If you should happen to disagree, please let me know.

A. B.

June 2013

INTRODUCTION

IT MAY NOT seem like it, but this is a book. I thought I might like to write one in serial form, for a newspaper, to appear together with all the worlds entrails passing through its pages. What attracted me to the idea was the fragility of the thinglike writing outside, standing atop a tower, with everyone looking on and the wind blowing, everybody passing by with so many things to do. There you are, unable to revise, turn back, or redesign the ladder. Whatever happens, happens. And then, the next day, the page will be used to wrap a head of lettuce or become a hat for a housepainter. Assuming people still make hats out of newspapers, like little boats floating on the seas of their hair.