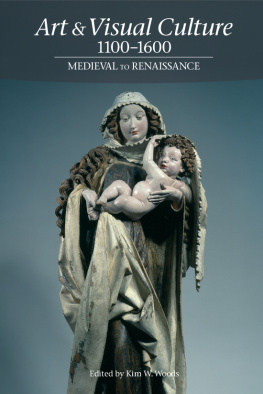

Central to each book is a concern with the ways in which the concept of art has developed over the course of time and how visual practices have both responded to and been shaped by these changing ideas. This first book in the series explores art in a range of media over five centuries of great change, during which art had a direct religious and social function.

All of the books in the series include teaching elements. To encourage the reader to reflect on the material presented, each chapter contains short exercises in the form of questions. These are followed by discursive sections.

Introduction

Kim W. Woods

This book considers the production and consumption of art from the Crusades through to the period of the Catholic Reformation. A study of such a wide chronological and geographical scope cannot be comprehensive, and it would be misguided even to attempt to provide a systematic overview of art covering five centuries. The case studies included here, all fascinating in their own right, have been selected because each also introduces themes and methods critical to the study of medieval and Renaissance art. The reader will therefore emerge with an overview of some of the essential principles, challenges and problems of studying the art history of this period.

The focus is on art in medieval and Renaissance Christendom, but this does not imply that Europe was insular during this period. The period witnessed the slow erosion of the crusader states in the Holy Land, finally relinquished in 1291 (see chapter 4), and of the Greek Byzantine world until Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453. Famously, Columbus made his voyage of discovery of the New World in 1492. Medieval Christendom could not but be aware of its neighbours. Trade, diplomacy and conquest connected Christendom to the wider world, which in turn had an impact on art. The luxury oriental fabrics painstakingly represented in paintings by Simone Martini (c.12841344), and the feather pictures made in Mexico for European collectors, are only two examples (chapters 3 and 5). It would have been possible to produce a book that focused exclusively on the cultural interaction between Christendom and its neighbours.

The important point to be made is that the medieval and Renaissance period was not parochial and neither were its artists. Any notion of the humble medieval artist oblivious to anything beyond his own immediate environment must be dispelled. This book shows that artists and patrons were well aware of artistic developments in other countries (chapter 2). Artists travelled both within and between countries and on occasion even between continents (chapters 3, 4 and 8). Such mobility was facilitated by the network of European courts, which were instrumental in the rapid spread of Italian Renaissance art (chapter 5). Europe-wide frameworks of philosophical and theological thought, reaching back to antiquity and governing religious art, applied albeit with regional variations throughout Europe (chapter 1), just as challenges in the form of the Protestant and Catholic Reformations rapidly became pan-European phenomena.

Art, visual culture and skill

The term visual culture is used in preference to art in this book for the fundamental reason that the arts before 1600 were very much more wide-ranging than they were subsequently defined. From the founding of the first art academy in Florence in 1563 up to the twentieth century, art has been understood primarily in terms of the three so-called arts of design: painting, sculpture and architecture, all of which were considered to demand talent and intellectual application as well as the acquisition of manual skill. Medieval art and Renaissance art present a challenge to this definition.

The Latin word ars signified skilled work; it did not mean art as we might understand it today, but a craft activity demanding a high level of technical ability including tapestry weaving, goldsmiths work or embroidery. Literary statements of what constituted the arts during the medieval period are rare, particularly in northern Europe, but proliferate in the Renaissance. They deliver the odd surprise. In 1504, the Netherlandish writer Jean Lemaire de Belges wrote a poem for his patron Margaret of Austria, sister of the ruler of the Netherlands, in which he listed prominent artists of the day. In addition to painters, he mentions book illuminators, a printmaker, tapestry designers and goldsmiths.1 Giorgio Vasari (151174), the biographer of Italian artists, claimed in his famous book Le vite de pi eccelenti pittori, scultori e architettori (Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects; first edition 1550 and revised 1568) that the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (13771446) was initially apprenticed to a goldsmith to the end that he might learn design.2 According to Vasari, several other Italian Renaissance artists are supposed to have trained initially as goldsmiths, including the sculptors Ghiberti (13781455) and Verrocchio (143588), and the painters Botticelli (c.14451510) and Ghirlandaio (1448/4994). The design skills necessary for goldsmiths work were evidently a good foundation for future artistic success. All of this calls into question the subsequent academic division between the so-called arts of design and crafts, and not least the relegation of goldsmiths to the realm of craft.

The term visual culture is also used for a second reason that is less to do with definition than with method. Including the various arts under the umbrella of visual culture implies their inseparability from the visual rhetoric of power on the one hand, and the material culture of a society on the other. Before 1500 at least, art did not signify painting or sculpture to be scrutinised in a gallery, but an aspect of the persuasive power and cultural identity of church, ruler, city, institution or individual. In this sense, art might be considered alongside ceremonies, for example, as strategies conveying social meaning or magnificence (see chapters 1, 2 and 5), or alongside coins and ceramics as aspects of identity (see chapter 4). Equally, visual culture serves as an eloquent indicator of gender, as shown in chapter 7.

If art is defined, as it was in later centuries, solely as an aesthetic entity prompting scrutiny for its own sake alone, then the purposefulness of the varied forms of art produced during the medieval and Renaissance period might appear to lie outside this definition. Yet objects were made that invited the most attentive scrutiny for their ingenuity in design while at the same time fulfilling a variety of functions. Purposefulness is also predicated on skills of looking and interpreting. No one in medieval times would have bothered with purposeful works of art unless they could assume that their contemporaries were vulnerable to their communicative power. For example, the wealthy lavished money on rich artefacts or dynastic portraits in part because they were an aspect of the social exclusiveness that a representative number of their entourage could notice and grasp. In reiterating the convention that religious art was particularly useful for those unable to read (chapter 1), medieval thinkers seem to have assumed that ordinary people too were capable of thoughtful looking. This suggests that attentive and intelligent scrutiny was a cultural skill that might, to a degree at least, be taken for granted by both patrons and artists during the medieval and Renaissance periods. Works of art might not have hung in galleries, but it seems that medieval and Renaissance audiences knew how to look at them.