This book is supported by the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs as part of the Burgess Programme, headed by the French Embassy in London by the Institut Franais du Royaume Uni

This one-volume edition published by Verso 2014

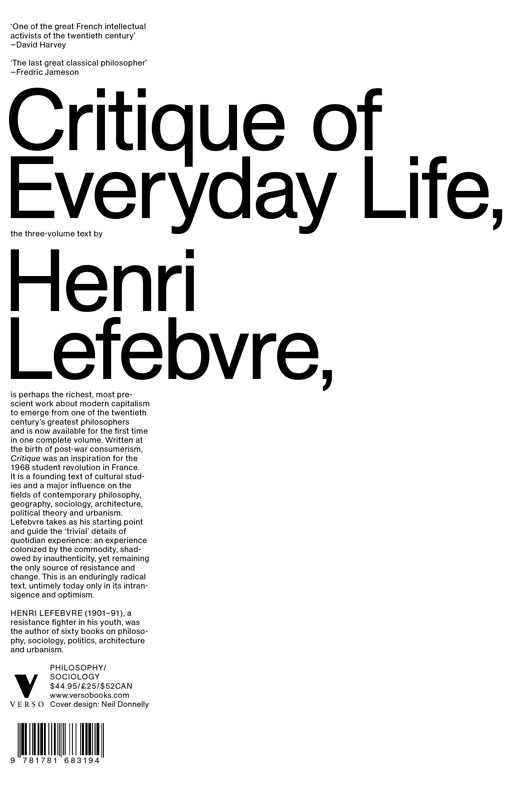

Critique of Everyday Life, Volume I: Introduction

First published by Verso 1991

Translation John Moore 1991, 2008, 2014

Preface Michel Trebitsch 1991, 2008, 2014

First published as Critique de la vie quotidienne I: Introduction

Grasset 1947; second edition with new foreword LArche Editeur 1958.

Critique of Everyday Life, Volume II: Foundations for a Sociology of the Everyday

First published by Verso 2002

Translation John Moore 2002, 2014

First published as Critique de la vie quotidienne II: Fondements dune sociologie de la quotidiennet

LArche Editeur 1961

Preface Michel Trebitsch 2002, 2014

Preface translation Gregory Elliott 2002, 2014

Critique of Everyday Life, Volume III: From Modernity to Modernism (Towards a Metaphilosophy of Daily Life)

First published by Verso 2005

Translation Gregory Elliott 2005, 2014

Preface Michel Trebitsch 2005, 2014

First published as Critique de la vie quotidienne III: De la modernit au modernisme (pour une metaphilosophie du quotidien)

LArche Editeur 1981

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors and translator have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-317-0 (PBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-318-7 (HBK)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-319-4 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-650-8 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Translators Note

Except when prefixed (Trans.), footnotes are from the original. Translations of quotations in the text are mine, except when the source title is given in English. Bibliographical details are presented in the original in a partial and unsystematic way, and wherever possible I have endeavoured to complete and standardize this information, a frequently difficult task, since the author uses his own translations of Marx. I wish to thank my colleagues Robert Gray, John Oakley and Adrian Rifkin for the advice and encouragement they have given me during the preparation of this project.

Preface

by Michel Trebitsch

What a strange status this book has, and how strange its destiny has been. If Henri Lefebvre can be placed alongside Adorno, Bloch, Lukcs or Marcuse as one of the main theoreticians of Critical Marxism, it is largely thanks to his Critique of Everyday Life (Critique de la vie quotidienne), a work which, though well known, is little appreciated. Perhaps this is because Lefebvre has something of the brilliant amateur craftsman about him, unable to cash in on his own inventions; something capricious, like a sower who casts his seeds to the wind without worrying about whether they will germinate. Or is it because of Lefebvres style, between flexibility and vagueness, where thinking is like strolling, where thinking is rhapsodic, as opposed to more permanent constructions, with their monolithic, reinforced, reassuring arguments, painstakingly built upon structures and models? His thought processes are like a limestone landscape with underground rivers which only become visible when they burst forth on the surface. Critique of Everyday Life is one such resurgence. One could even call it a triple resurgence, in that the 1947 volume was to be followed in 1962 by a second, Fondements dune sociologie de la quotidiennet, and in 1981 by a third, De la modernit au modernisme (Pour une mtaphilosophie du quotidien). At the chronological and theoretical intersection of his thinking about alienation and modernity, Critique of Everyday Life is a seminal text, drawn from the deepest levels of his intellectual roots, but also looking ahead to the main preoccupation of his post-war period. If we are to relocate it in Lefebvres thought as a whole, we will need to go upstream as far as La Conscience mystifie (1936) and then back downstream as far as Introduction la modernit (1962).

Henri Lefebvre or Living Philosophy

The year 1947 was a splendid one for Henri Lefebvre: as well as Critique of Everyday Life, he published Logique formelle, logique dialectique, Marx et la libert and Descartes in quick succession. This broadside was commented upon in the review La Pense by one of the Communist Partys rising young intellectuals, Jean Kanapa, who drew particular attention to the original and creative aspects of Critique of Everyday Life. With this book, wrote Kanapa, philosophy no longer scorns the concrete and the everyday. By making alienation the key concept in the analysis of human situations since Marx, Lefebvre was opening philosophy to action: taken in its Kantian sense, critique was not simply knowledge of everyday life, but knowledge of the means to transform it. Thus in Lefebvre Kanapa could celebrate the most lucid proponent of living philosophy today.

Critique of Everyday Life thus appears to be a book with a precise date, and this date is both significant and equivocal. Drafted between August and December 1945, published in February 1947, according to the official publishers date, it reflected the optimism and new-found freedom of the Liberation, but appeared only a few weeks before the big freeze of the Cold War set in. In the enthusiasm of the Liberation, it was hoped that soon life would be changed and the world transformed, as Henri Lefebvre recalled in 1958 in his Foreword to the Second Edition. The year 1947 was pivotal, Janus-faced. It began in a mood of post-war euphoria, then, from March to September, with Trumans policy of containment and Zhdanovs theory of the division of the world into two camps, with the eviction of the Communist ministers in France and the launching of the Marshall Plan, in only a few months everything had been thrown in the balance, including the

In a way both were after the same quarry: Lefebvres pre-war themes of the total man and his dialectic of the conceived and the lived were echoed by Sartres definition of existence as the reconciliation between thinking and living. At that time Lefebvre was certainly not unknown: from the beginning of the 1930s the books he wrote single-handedly or in collaboration with Norbert Guterman had established him as an original Marxist thinker. But his pre-war readership had remained limited, since philosophers were suspicious of Marxism and Marxists were suspicious of philosophy. Conversely, after 1945, he emerged as the most important expert on and vulgarizer of Marxism, as an entire generation of young intellectuals rushed to buy his Que sais-je? on Marxism and the new printing of his little