THEODOR W. ADORNO

Against Epistemology:

A Metacritique

Studies in Husserl and the

Phenomenological Antinomies

Translated by Willis Domingo

Originally published as Zur Metakritik der Erkenntnistheorie Suhrkamp Verlag,

Frankfurt am Main 1970

English translation Basil Blackwell Publisher Limited 1982

First published in English 1982

This edition first published in 2013 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of

criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6966-3

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6537-5

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6538-2(pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Group Limited, Bodmin, Cornwall

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently

overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits

in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

For Max

Preface

Portions of an extensive manuscript produced in Oxford during my first years of emigration, 193437, have been selected and reworked. For I felt their scope and significance kept them above simple academic dispute. Without sacrificing contact with the subject matter and thus the obligation to argue effectively against a method designed to forego the need for argument, the question I shall broach by means of a concrete model is the possibility and truth of epistemology in principle. Husserls philosophy is the occasion and not the point of this book. Thus it is not to be presented as a completed whole and then subject to some sort of comparison. As is appropriate for a thought which does not submit to the idea of a system, I seek to organize what is thought around its focal points. The result was a discontinuous and yet most closely connected, mutually supporting set of individual studies. Overlapping was unavoidable.

This book inclines toward substantive philosophy. The critique of Husserl aims across his work at the tendency, which was of such emphatic concern to him and which he felt German philosophizing appropriated much more fundamentally than is currently admitted. The book is, nevertheless, not systematic in the sense of the traditional contrast to history. If it challenges the very concept of system, it also seeks to grasp an historical core inside the substantive question. For the historical/systematic distinction also falls under the critique of this book.

Nowhere do I pretend it is philological or hermeneutic. Secondary literature is ignored. A number of Husserls own texts, especially in the second volume of the Logical Investigations, are a densely complex thicket and certainly even ambiguous. Should my interpretation occasionally be in error, I would be the last to defend it. On the other hand, I could not respect programmatic declarations, and had to abide by what the texts themselves appeared to me to say. Thus I did not allow myself to be intimidated by Husserls assurance that pure phenomenology is not epistemology, and that the region of pure consciousness has nothing to do with the concept of the structure of the given in the immanence of consciousness (Bewutseinsimmanenz) as it was known to pre-Husserlian criticism. How exactly Husserl distinguishes himself from this criticism is just as much a matter of discussion as whether that distinction is binding or not.

My analysis is confined to what Husserl himself published, with preference for the authentic phenomenological writing on which the restoration of ontology was based over the later works, in which Husserls phenomenology betrayed itself and reverted into a subtly modified neo-Kantianism. Yet, since the revision of pure phenomenology came not from the convictions of its creator, but was rather imposed by its object, I thus felt free to turn to the Formal and Transcendental Logic and the Cartesian Meditations, whenever the drift of the discussion demanded it. All the pre-phenomenological writings have been ignored, in particular the Philosophy of Arithmetic, as well as the posthumous publications. Comprehensiveness was never my aim. The analyses Husserl actually carried through and to which he himself devoted his energy provoked my attention more than the total edifice.

Yet my intention was certainly not the mere critique of details. Instead of disputing individual epistemological issues, micrological procedure should stringently demonstrate how such questions surpass themselves and indeed their entire sphere. The themes which compose such a movement are summarized in the Introduction. The four studies alone, however, are responsible for the cogency of what I have developed.

Three of the chapters have appeared in Archiv fr Philosophie. Chapter 4 was published separately as early as 1938 under the title Zur Philosophie Husserls (Band 3, Heft 4). Chapters 1 and 2 came out in 1953 (Band 5, Heft 2 and Band 6, Heft 1/2). The final chapter in particular has been thoroughly revised since its first appearance.

Frankfurt

Easter 1956

Introduction

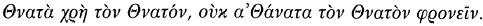

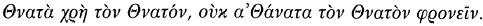

A mortal must think mortal and not immortal thoughts.

Epicharmus, Fragment 20

Procedure and Object

The attempt to discuss Husserls pure phenomenology in the spirit of the dialectic risks the initial suspicion of caprice. Husserls programme deals with a sphere of being of absolute origins, philosophy, including Husserls, only gropingly and in fragments rediscovered for itself is the power of contradiction. This power turns against itself and against the idea of absolute knowledge. Thought, by actively beholding, rediscovers itself in every entity, without tolerating any restrictions. It breaches, as just such a restriction, the requirement to establish a fixed ultimate to all its determinations. It thus also undermines the primacy of the system and its own content.

The Hegelian system must indeed presuppose subjectobject identity, and thus the very primacy of spirit which it seeks to prove. But as it unfolds concretely, it confutes the identity which it attributes to the whole. What is antithetically developed, however, is not, as one would no doubt currently have it, the structure of being in itself, but rather antagonistic society. For it is no coincidence that all the stages of the Phenomenology of Spirit which appears as self-movement on the part of the concept refer to the stages of antagonistic society. What is compelling about both the dialectic and the system and is inseparable from their character of immanence or logicality, is made to approximate real compulsion by their own principle of identity. Thought submits to the real compulsion of societal debt relations and, deluded, claims this compulsion as its own. Its closed circle brings about the unbroken illusion of the natural and, in the end, the metaphysical illusion of being. Dialectic, however, constantly brings this appearance back to nothing.

In the face of this, Husserl appealed to the end, in the name of his serried complete presentation of phenomenology, to that Cartesian illusion which applies to the absolute foundations of philosophy. He would like to revive