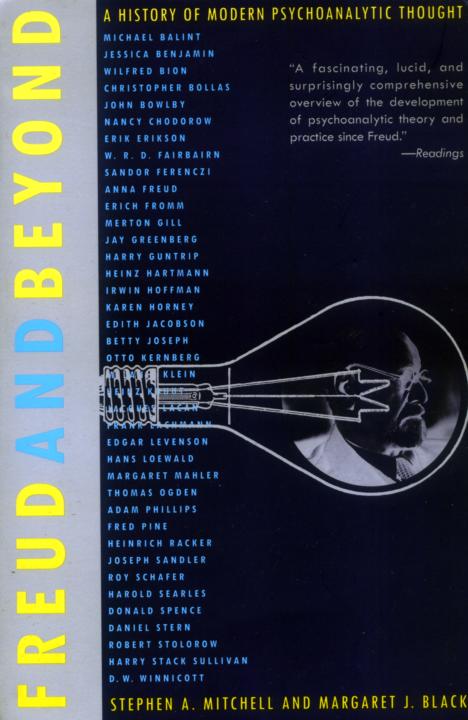

OTHER BOOKS BY STEPHEN A. MITCHELL

STEPHEN A. MITCHELL

MARGARET J. BLACK

For Caitlin and Samantha

Those who know ghosts tell us that they long to be released from their ghost life and led to rest as ancestors. As ancestors they live forth in the present generation, while as ghosts they are compelled to haunt the present generation with their shadow life.

-Hans Loewald

CON1[NIS

ix

xv

ACKNOWLE.DGMFNTS

Tis book grew out of our shared excitement about the teaching of psychoanalytic ideas, a process that has involved us for over twenty-five years: first as students and supervisees, then as teachers, supervisers, and consultants and educational administrators. We have seen psychoanalytic concepts taught well, and we have seen them taught poorly. "Everything you do," declared an early teacher to start his course, "is determined by forces inside you of which you are totally unaware." This kind of approach makes psychoanalytic ideas seem esoteric and alien, the claims made by psychoanalytic theorists arrogant and ominous. When taught well, psychoanalytic concepts have the capacity to enrich rather than deplete, to empower rather than diminish, to deepen experience rather than haunt it. It is with this ideal in mind that we have approached the writing of this book, hoping that the reader will find the concepts contained in it stimulating, challenging, and fundamentally graspable.

Our subject matter is vast. Only a portion of all the existing concepts could be presented, and only a portion of the relationships among them explored. We were regularly confronted with impossible choices: whether to fill out and make accessible a particularly difficult concept, or whether to use the space to discuss the work of one more person we felt had made a valuable contribution to psychoanalytic understanding. We know that we will never be fully reconciled to all the choices we made, but console our selves with the hope that if we succeeded in presenting what we could include in an engaging enough manner, the book could provide for the reader an entree into the psychoanalytic literature (where everything is available).

Many colleagues read and commented on various portions of various versions of this manuscript. This is not to imply that they agree with all we have written. The selection and the manner of presentation were, ultimately, our choices. We are very grateful for the imput of: Neil Altman, Lewis Aron, Diane Barth, Anthony Bass, Martha Bernth, Phillip Bromberg, Jody Davies, Sally Donaldson, James Fosshage, Kenneth Frank, Jay Greenberg, Adrienne Harris, Irwin Z. Hoffman, Frank Lachmann, Clem Loew, Susan McConnaughy, John Muller, Sheila Ronsen, and Charles Spezzano.

Those to whose generosity we are most indebted are our patients, whose willingness to allow us to explore their lives with them is the foundation for all the thoughts and concepts developed here. It is a great irony indeed that, because of confidentiality, patients can never be thanked by name. We are also deeply grateful to our many supervisees whose openness and generosity with their own work, both in moments of despair and in moments of mastery, have allowed us to better illustrate the constructive impact of psychoanalytic theory on the clinical process.

We both also feel extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to teach psychoanalytic ideas to interested students in many settings. The selection of concepts presented here and the way they are developed were honed by the reactions and challenges of our students. It is no secret that the best way to learn anything is to muster the temerity to teach it, and we are grateful to the students and supervisees who have shared that kind of learning experience with us.

I (MB) would like to express my thanks to the National Institute for the Psychotherapies, where, as a member of the board of directors and as director of continuing education, I have had the privilege of being intimately involved in the shaping of psychoanalytic education in a community that fosters intellectual freedom and creative thinking. Many of my thoughts, about effective teaching as well as meaningful learning, have crystallized in these experiences. I have had the additional pleasure of serving on the faculty there as well as at the Postgraduate Center for Mental Health, the Institute for the Psychoanalytic Study of Subjectivity, and the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California, all institutes that give a great deal of careful thought to the teaching of psychoanalytic ideas.

I (SM) want to thank the William Alanson White Institute and the New York University Postdoctoral Program, on whose faculty I have served for many years. They have provided me with exciting intellectual communities and an academic freedom that has made possible the development of my own thought. I also have appreciated the opportunities for teaching at: the National Institute for the Psychotherapies; the doctoral program at Teachers' College, Columbia University; the Washington School of Psychiatry; and various local chapters of Division 39 (Psychoanalysis) of the American Psychological Association, in Boston, Denver, New Haven, San Francisco, Seattle, and Toronto. Most of all, I am indebted to the members of the reading groups with whom I have been meeting weekly or biweekly for years to discuss psychoanalytic ideas and the challenges of clinical work.

Jo Ann Miller at Basic Books was encouraging and helpful throughout, and Deborah Rosenzweig's meticulous eye was a great help and reassurance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Most of all, we would like to express our gratitude to our daughters, Caitlin and Samantha, whose spirit and good humor have always served as a source of inspiration for us.

PREFACE

what is psychoanalysis?

Movies and cartoons offer images of a patient lying on a couch, speaking endlessly into a vacuum, while a silent, colorless, older gentleman with a beard takes notes. Many people who are unfamiliar with psychoanalysis fear it as a coward's way out, an admission of defeat, a ceding of control and authority to a stranger.