Can Love Last?

The Fate of Romance over Time

STEPHEN A. MITCHELL

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

Copyright 2002 by the Estate of Stephen A. Mitchell

All rights reserved

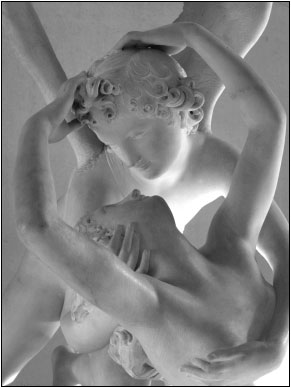

Frontispiece: Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Eros Kiss (detail). The Louvre, Paris. Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

M. C. Escher, Drawing Hands 2001 Cordon Art B.V.Baarn

Holland. All rights reserved.

M. C. Escher, Mbius Strip I 2001 Cordon Art B.V.Baarn

Holland. All rights reserved.

M. C. Escher, Relativity 2001 Cordon Art B.V.BaarnHolland.

All rights reserved.

Fascination Begins in the Mouth by Mary Gordon. Reprinted by permission of Sterling Lord Literistic, Inc. Copyright by Mary Gordon.

Excerpt from The Ballad of the Sad Caf, The Ballad of the Sad Caf and Collected Short Stories by Carson McCullers. Copyright 1936, 1941, 1942, 1950, 1955 by Carson McCullers. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

From The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens by Wallace Stevens, copyright 1954 by Wallace Stevens. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

Fern Hill by Dylan Thomas, from The Poems of Dylan Thomas , copyright 1945 by The Trustees for the Copyrights of Dylan Thomas. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. and David Higham Associates.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mitchell, Stephen A., 1946

Can love last?: the fate of romance over time / by Stephen A. Mitchell.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07848-0

1. Man-woman relationshipsPsychological aspects. 2. Love. I. Title.

HQ801 .M59 2002

306.7dc21 2001044452

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

FOR

Margaret, Caitlin, and

Samantha

Contents

Foreword

Margaret Black, C.S.W.

OUR WORLD IS FILLED with brilliant thinkers. We are regularly flooded with amazing information: details on our apparent potential to artificially replicate human intelligence, the intricacies of genetics, the increasing likelihood of producing a viable human clone. The issues that touch most directly on our everyday experience, however, remain somehow opaque, mysterious, conceptually documented yet experientially unresolved and unsatisfying. We have been granted one life to live. We want it to be fulfilling, meaningful. We want it to sustain love and passion. Many of us long for passion that will emerge and endure in a relationship with a particular important other. The questions seem easy enough to frame: What allows us to feel that our intimate relationships are passionate as well as meaningful? Can this kind of meaningful passion last over time? How can it survive, given the challenges we subject it toliving busy lives, dealing with everyday familiarity, raising children, growing older?

Our best thinkers seem to have little to offer us here. Despite his genius and astonishing productivity as the creator of psychoanalysis, Freuds formulations have not been particularly helpful, certainly not very optimistic. Within his conception of human psychology, sexual passion and enduring love have separate derivations, one primitive, one civilized, locking them in an inversely proportional relationship. A passionate sexual relationship with ones partner bodes poorly for tenderness and respect and vice versa. Psychoanalysis, which prides itself on reaching the deepest understanding of emotional life, seemed to have taken us to a conceptual dead end. Decades have passed since Freud lived and wrote, yet there has been astonishingly little new thinking in an area that affects us all so fundamentally.

Having lived with Stephen for nearly thirty years, having worked with him and raised a family, one of the qualities I always loved about him was his ecumenical approach to ideas. His kind of mind flourished in the contemporary postmodern intellectual climate, joyfully constructing and deconstructing, combining and recombining ideas gleaned from his extensive reading and clinical work.

Blessed with rigorous intellectual honesty, good thinking fascinated himno matter what the discipline. He loved ideas, loved to play with them, to stretch them, to see how they held up on relentless probing, and, above all, to share them with others. He appreciated the thinking of others in a way that made their ideas seem like generous gifts for which he was deeply grateful. Accompanying him to a bookstore was like watching a kid in a candy store. We would inevitably leave, bags heavy with philosophy texts, poetry, a recently published novel, some obscure publication on physics that caught his attention, books on the mind, artificial intelligence, Buddhism, and, sometimes on psychoanalysis. There was a kind of implicit contest in our lives together: Would the prints I had purchased be successfully framed and hung on the wall before he claimed the wall space for another set of bookshelves? He listened to taped courses on the history of music while he exercised. He loved the fine presentation of ideas and read passages aloud to the family when he ran across something with a particularly fine turn of phrase or thought-provoking presentation.

Inheriting from his family of origin a healthy disdain for authoritarian structure, it quickly became clear that Stephens thinking could not be constrained by rigidly held principles within psychoanalysis, no matter how distressing or disruptive his challenges were to the profession. Early in his own career, shortly after he had completed his training, he was among the first authors within the psychoanalytic tradition to openly and effectively challenge the then firmly held belief that homosexuality was fundamentally pathological (1978, 1981), an effort that eventually resulted in its removal from the official psychiatric nomenclature of pathology.

Stephen rather romped through the extensive literature in psychoanalysis which was, at the time, sharply segregated into competing theoretical traditions and heavily dominated by the classical Freudian approach, an approach that declared alternative positions to be nonanalytic and therefore marginal. In an effort to encourage more creative thinking in the field, he launched his own journal called Psychoanalytic Dialogues , employing what was at the time a revolutionary format of publishing the nonclassical marginalized voices within psychoanalysis as well as organizing respectful discussions among analysts of differing theoretical persuasions so that clinical approaches and theoretical formulations could be more thoughtfully and comparatively considered. He organized conferences, inviting representatives of diverse academic disciplines to consider a common problem in human experience.