Stephen Mitchell - The Book of Job

Here you can read online Stephen Mitchell - The Book of Job full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

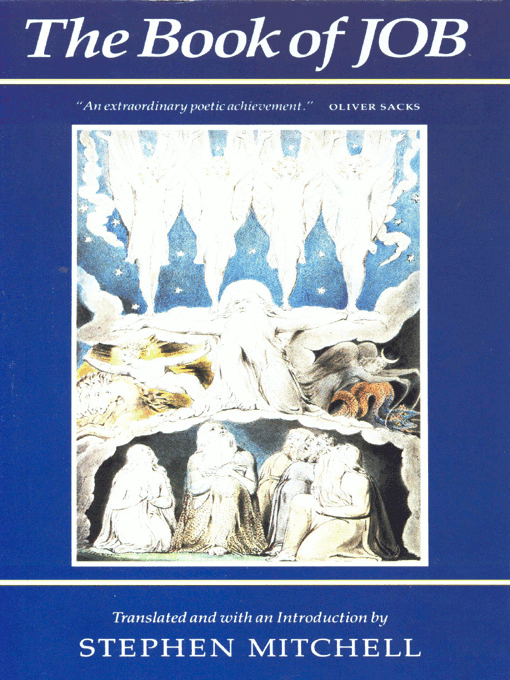

- Book:The Book of Job

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Book of Job: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Book of Job" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Book of Job — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Book of Job" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Yet however foreign thepoet originally was, his theme is the great Jewish one, the theme of thevictim. Someone must have slandered J., because one morning he was arrested,even though he had done nothing wrong. That is what makes Job the central parable of our post-Holocaust age, and gives such urgency to itsdeep spiritual power.

goodness and piety appear. TAO TE CHING To introduce his poem, the author retells a legend that wasalready ancient centuries before he was born. It concerns a righteous man whofor no reason has been deprived of all the rewards of his righteousness; in themidst of great suffering he remains steadfast and perfectly pious, stillblessing the Lord as before.

You have heard of the patience of Job, theEpistle of James says, and it is this legendary, patient Jobnot thedesperate and ferociously impatient Job of the poem who, ironically enough,became proverbial in Western culture. We can respect thelegend on its own naive terms, and can appreciate the skill with which theauthor retells it: the chilling conversations in heaven; the climax where Jobsubmits, as if he were a calmer, more insightful Adam who has just eaten thebitter fruit of the Tree of Knowledge and, eyes opened, sees that he is naked.But if we read the prologue more seriously, less objectively, we may beslightly repulsed by its heros piety. There is something so servile about himthat we may find our-selves siding with his impatient wife, wanting to shout, Come on, Job; stand up like a man; curse this god, and die! The character called the Lord can do anything to himhave his daughtersraped and mutilated, send his sons to Auschwitz and he will turn the othercheek. This is not a matter of spiritual acquiescence, but of mere capitulationto an unjust, superior force. When we look atthe world of the legendary Job with a probing, disinterestedly satanic eye, wenotice that it is suffused with anxiety. Job is afraid of God, as well he mightbe.

He avoids evil because he realizes the penalties. He is a perfect moralbusinessman: wealth, he knows, comes as a reward for playing by the rules, andgoodness is like money in the bank. But, as he suspects, this world isthoroughly unstable. At any moment the currency can change, and the Lord, byhanding Job over to the power of evil, can declare him bankrupt. No wonder hismind is so uneasy. He worries about making the slightest mistake; when he hashis children come for their annual purification, it is not even because theymay have committed any sins, but may have had blasphemous thoughts.

Thesuperego is riding high. And in fact, at the climax of his first speech in thepoem, Job confesses that his worst fears have happened; / [his] nightmareshave come to life. This is not a casual statement, added as a poetic flourish.Anxieties have a habit of projecting them-selves from psychological intophysical reality. Jobs pre-monition turned out to be accurate; somewhere heknew that he was precariously balanced on his goodness, like a triangle on itsapex, just waiting to be toppled over. There is even a perverse sense ofrelief, as if that heavy, responsible patriarch-world had been groaning towarddeliverance. For any transformation to occur, Job has to be willing to let hishidden anxieties become manifest.

He must enter the whirlwind of his ownpsychic chaos before he can hear the Voice. As Maimonides was thefirst to point out, Job is a good man, not a wise one. The ascription ofperfect integrity, which both the narrator and the Lord make, seems valid only in a limited sense. The Hebrew says tam v-yashar, which literally means whole (blameless) andupright. Well, yes: Job has never committed even the most venial sin, inaction or in thought. (For that very reason, his later agony and bewildermentare more terrible than Josef K.s in The Trial.) In a broadersense, though, Job is not whole.

He is as far from spiritual maturity as he isfrom rebellion. Rebelliousness the passionate refusal to submit is, in fact,one of the qualities we admire in the Job of the poem: Be quiet nowlet me speak; whatever happens will happen. I will take my flesh in my teeth, hold my life in my hands. He [God] may kill me, but I wont stop; I will speak the truth, to his face. Ifwe compare the legendary figure with the later Job, especially in the greatsummation that concludes the central dialogue, we can recognize that even hisvirtue lacks a certain generosity and wholeheartedness. That is why the betdoesnt prove much.

Job is too terrorized, from within his squalor, to doanything but bless the Lord: for all he knows, there might bean even more horrible con-sequence in store. The real test will come later, inthe poem, when he feels free to speak with all of himself, to sayanything. There is a further irony about tam v-yashar. When Job is handed over to the good graces ofthe Accuser, he is turned into the opposite of what the words mean in theirmost physical sense. He becomes not-whole: broken in body andheart. He becomes not-upright: pulled down into the dust bythe gravity of his anguish.

The author moves us to heaven afterthe prologues first scene, and we may be tempted to admire his boldness. Butheaven, it turns out, is only the court of some ancient King of Kings, completewith annual meetings of the royal council and a Satan (or Accusing Angel). As below, so above. Jung, in his Answer to Job,makes the point that, psychologically, the Accuser is the embodiment of theLords doubt. In a more naive version of the legend, the god in his divinemyopia would himself doubt the disinterestedness of his obedient human andwould decide to administer the test on his own. Here, though the Accuserostensibly plays the role of the villain, it is the Lord who provokes him.Did you notice my servant Job? How can the Accuser not take up the challenge?After all, thats his job.

As Jung also points out, this god ismorally much inferior to the prologues hero. We would have to be in-sensitiveor prejudiced not to be nauseated by the very awareness of the Lords secondstatement to the Accuser: He is holding on to his wholeness, even after youmade me torment him for no reason, and by the calm cruelty of All right: heis in your power. Just dont kill him. Nevertheless, if we wantto be serious about the poem, we mustnt take the legend too seriously. Thereis a profound shift when the verse dialogue begins; the change in language is achange in reality. Compared to Jobs laments (not to mention the Voice from theWhirl-wind), the world of the prologue is two-dimensional, and its divinitiesare very small potatoes.

It is like a puppet show. The author first brings outthe patient Job, his untrusting god, and the chief spy/prosecutor, and has thefigurines enact the ancient story in the puppet theater of his prose. Then,behind them, the larger curtain rises, and flesh-and-blood actors begin tovoice their passions on a life-sized stage. Finally, the vast, unnamable Godappears. How could the author have returned to the reality of the prologue foran answer to the hero of the poem? That would have meant the Lord descendingfrom the sky to say, Well, you see, Job, it all happened because I made thisbet No, the god of the prologue is left behind as utterly as thenever-again-mentioned Accuser, swallowed in the depths of human suffering intowhich the poem plunges us next.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Book of Job»

Look at similar books to The Book of Job. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Book of Job and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.