The passages on are reprinted from Tao Te Ching:

A New English Version with Foreword and Notes by Stephen Mitchell. Translation copyright 1988 by Stephen Mitchell. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins.

The Message of the Gita is reprinted from The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. XLI . Reprinted by permission of the Navajivan Trust.

Copyright 2000 by Stephen Mitchell

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Harmony Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Harmony Books is a registered trademark, and the Circle colophon is a trademark of Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Harmony Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 2000, and subsequently published in paperback by Three Rivers Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 2002.

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN- P UBLICATION D ATA

Bhagavadgita. English

Bhagavad Gita: a new translation / by Stephen Mitchell.1st ed.

I. Mitchell, Stephen, 1943 . II. Title.

BL11 38.62. E5 2000b

294.592404521dc21 00-028286

ISBN 978-0-609-81034-7

eISBN 978-0-307-41989-7

v3.1_r4

BY STEPHEN MITCHELL

POETRY

Parables and Portraits

FICTION

The Frog Prince

Meetings with the Archangel

NONFICTION

The Gospel According to Jesus

TRANSLATIONS AND ADAPTATIONS

Bhagavad Gita

Real Power: Business Lessons from the Tao Te Ching

(with James A. Autry)

Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon:

Selected Poems of Pablo Neruda

Genesis

Ahead of All Parting:

The Selected Poetry and Prose of Rainer Maria Rilke

A Book of Psalms

The Selected Poetry of Dan Pagis

Tao Te Ching

The Book of Job

The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai

(with Chana Bloch)

The Sonnets to Orpheus

The Lay of the Love and Death of Cornet Christoph Rilke

Letters to a Young Poet

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke

EDITED BY STEPHEN MITCHELL

The Essence of Wisdom:

Words from the Masters to Illuminate the Spiritual Path

Bestiary: An Anthology of Poems about Animals

Song of Myself

Into the Garden:

A Wedding Anthology (with Robert Hass)

The Enlightened Mind: An Anthology of Sacred Prose

The Enlightened Heart: An Anthology of Sacred Poetry

Dropping Ashes on the Buddha:

The Teaching of Zen Master Seung Sahn

FOR CHILDREN

The Creation (with paintings by Ori Sherman)

BOOKS ON TAPE

Bhagavad Gita

Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon

The Frog Prince

Meetings with the Archangel

Real Power

Bestiary

Genesis

Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus

The Gospel According to Jesus

The Enlightened Mind

The Enlightened Heart

Letters to a Young Poet

Parables and Portraits

Tao Te Ching

The Book of Job

Selected Poems of Rainer Maria Rilke

In honor of

Shri Ramana Maharshi

Introduction

I

O ne of the best ways of entering the Bhagavad Gita is through the enthusiasm of Emerson and Thoreau, our first two American sages. Emerson mentions the Gita often in his Journals, with the greatest respect:

It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spake to us, nothing small or unworthy but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age & climate had pondered & thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.

Thoreau speaks of it in awed superlatives:

The reader is nowhere raised into and sustained in a higher, purer, or rarer region of thought than in the Bhagvat-Geeta. Beside [it], even our Shakespeare seems sometimes youthfully green and practical merely.

What a revelation the Gita must have been for minds predisposed to its largehearted vision of the world. And what a delight to stand behind Emerson and Thoreau, reading over their shoulders as they discover this stupendous and cosmogonal poem in which, from the other side of the globe, across so many centuries, they can hear the voice of the absolutely genuine. Here is a kinsman, an elder brother, telling them truths that they already, though imperfectly, know, truths that are vital to them and to us all. In the Gitas wisdom, as in an ancient, clear mirror, they find that they can recognize themselves.

Souls who love God, a Sufi sheikh said a thousand years ago, know one another by smell, like horses. Though one be in the East and the other in the West, they still feel joy and comfort in each others talk, and one who lives in a later generation than the other is instructed and consoled by the words of his friend.

II

Bhagavad Gita means The Song of the Blessed One. No one knows when it was written; some scholars date it as early as the fifth century B.C.E. , others as late as the first century C.E . But there is general scholarly consensus that in its original form it was an independent poem, which was later inserted into its present context, Book Six of Indias national epic, the Mahabharata.

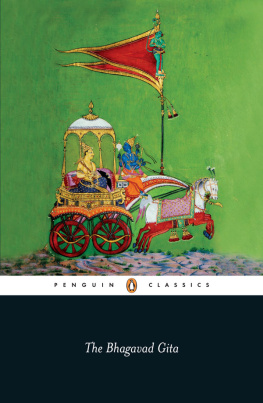

The Mahabharata is a very long poemeight times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combinedthat tells the story of a war between the two clans of a royal family in northern India. One clan is the Pandavas, who are portrayed as paragons of virtue; they are led by Arjuna, the hero of the Gita, and his four brothers. Opposing them are the forces of the Kauravas, their evil cousins, the hundred sons of the blind King Dhritarashtra. At the conclusion of the epic, the capital city lies in ruins and almost all the combatants have been killed.

The Gita takes place on the battlefield of Kuru at the beginning of the war. Arjuna has his charioteer, Krishna (who turns out to be God incarnate), drive him into the open space between the two armies, where he surveys the combatants. Overwhelmed with dread and pity at the imminent death of so many brave warriorsbrothers, cousins, and kinsmenhe drops his weapons and refuses to fight. This is the cue for Krishna to begin his teaching about life and deathlessness, duty, nonattachment, the Self, love, spiritual practice, and the inconceivable depths of reality. The wondrous dialogue that fills the next seventeen chapters of the Gita is really a monologue, much of it wondrous indeed, which often keeps us dazzled and asking for more, as Arjuna does:

for I never can tire of hearing

your life-giving, honey-sweet words. (10.18)

The incorporation of the Gita into the Mahabharata has both its fortunate and its unfortunate aspects. It gives a thrilling dramatic immediacy to a poem that is from beginning to end didactic. Krishna and Arjuna speak about these ultimate matters not reclining at their ease, or abstracted from time and place, but between two armies about to engage in a devastating battle. We see the ranks of warriors waiting in the adrenaline rush before combat, keying up their courage, drawing their bows, glaring across the battle lines; we hear the din of the conch horns, the neighing of the horses, the thunder of the captains and the shouting. Then, suddenly, everything is still. The armies are halted in their tracks. Even the flies are caught in midair between two wingbeats. The vast moving picture of reality stops on a single frame, as in Borgess story The Secret Miracle. The moment of the poem has expanded beyond time, and the only characters who continue, earnestly discoursing between the silent, frozen armies, are Arjuna and Krishna.