I

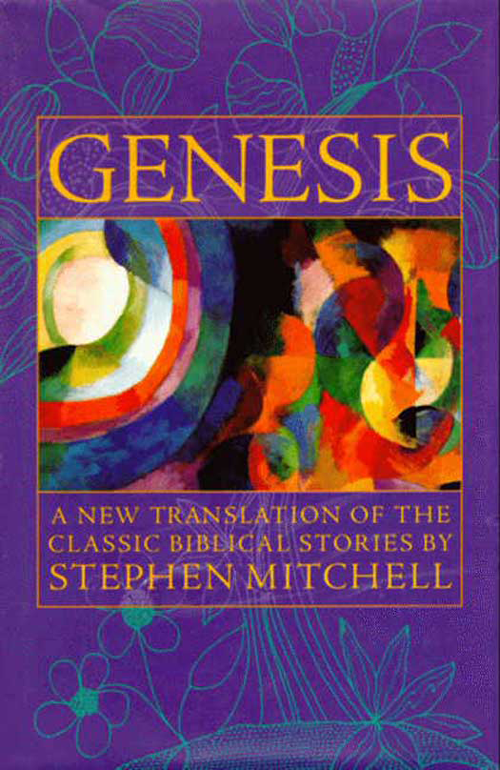

I had no intention of translating Genesis until, on the day before the Fourth of July, 1994, Bill Moyers called and invited me to participate in his PBS series. I told him I would think about it and get back to him in three days.

Actually, it wasnt thinking that I did during those three days. It was a kind of alert waiting.

Do you have the patience to wait

till your mud settles and the water is clear?

Can you remain unmoving

till the right action arises by itself?

I knew that much of Genesis spoke to me without intimacy, in the tones of a stranger; much of it didnt speak to me at all. If the fellow inside who makes my decisions required a wholehearted love for the book as a prerequisite, I would have to say no.

I soon realized that this was a matter of affinity. If I could find even one passage in Genesis where I had the kind of umbilical connection that I felt with the Job poet, or with Rilke or Lao-tzu, that might be enough. During the first hour of musing on the question, I found five. There was the verse at the end of chapter I when God calls the world very good: a verse that had lit up for me in the mid-seventies, after several years of intensive meditation, as the perfect metaphor for the spaciousness of a mind in which repose and insight are synonymous. Then, Abrams response to the call in chapter 12, a paradigm for every spiritual departure. There was the story of Jacob and Rachel, especially 29:20 (And Jacob served seven years for Rachel; and they seemed to him just a few days, so great was his love for her), a verse that described a crucial aspect of my own inner practice and was is for me the most moving verse in the entire Bible. Jacob and the (So-Called) Angela an enormously important story while I was training with my old Zen master, showed me that not only wrestling with but defeating God is a necessary rite of passage to spiritual freedom. And finally the great Joseph and His Brothers, a story of descent, transformation, and mastery, with an insight-filled, all-embracing forgiveness at its core. In addition, I had long been fascinated with Adam, Eve, and the serpent, and with The Binding of Isaac: profound, brilliant stories that rise from the depths of the unconscious mind, uncensored, unfiltered, dark, rich, unassimilable, compelling, and dangerous if taken at surface value the first one, as interpreted by the Church, a catastrophe in the history of our culture; both of them crying out for midrash, creative transformation, to make them true.

So the deep connections were there, and I knew that I could accept the invitation with a sense of integrity. But the process felt incomplete, as if one more step was necessary. That step appeared at the end of the second day. If I agreed to talk about Genesis, I would first have to translate it: to confront it in its entirety, immersemyself in it, live with it in the kind of intimacy that the process of translation requires. Once I had done that, I would know it through and through, the way Adam knew Eve. Even if there were things about it that I disliked, it would have become part of me, and I could dislike these things from the inside.

I had no illusions about the actual work of translation. Some of it would be interesting. Some of it would be exquisitely dull the genealogies written by P, the Priestly Writer (that adding machine among poets); the absurd patchwork of Abram and the Kings, which I would have to translate into an equally clumsy English; the late, shoddy accounts of Joseph in power that are stapled onto what Tolstoy called the most beautiful story in the world. None of the work would have the fascination of whats difficult, the passionate challenge of translating great poetry. But I was sure that I would learn a lot.

The mud had settled, considerately on schedule. I called Bill Moyers and said yes.

II

The great Russian poet Boris Pasternak identified the central issue in the art of translation when he said, The average translator gets the literal meaning right but misses the tone; and tone is everything. This is just as true of prose as of poetry. Tone is the life-rhythm of a mind. Reading a translation that renders a great writers words without re-creating their tone is like listening to a computer play Mozart.

My method in establishing the tone of this Genesis was to listento the Hebrew with one ear and with the other ear to hear into existence an equivalent English. In the process I had to filter out the sound of the King James Version, insofar as that is possible. English-speaking readers usually think of biblical language as Elizabethan: magniloquent, orotund, liturgical, archaic, full of thees and thous and untos and thereofs and prays. But ancient Hebrew, especially ancient Hebrew prose, is in many ways the opposite of that. Its dignity comes from its supreme simplicity. It is a language of concision and powerful earthiness, austere in its vocabulary, straightforward in its syntax, spare with its adjectives and adverbs a language that pulses with the energy of elemental human truths.

My job was to re-create this massive dignity and simplicity in an English that felt like it was mine. Dignity is not, I think, a quality you can aim at; it is a function of a writers sincerity, and it arises on its own in a translation if you have listened deeply enough to the original text and have at the same time been faithful to the genius of the English language. Simplicity is a bit easier to talk about. It doesnt only mean using as few words as possible. It is also a matter of finding a language that sounds completely natural, unliterary, in some sense unwritten: the words of a voice telling ancient stories without adornment and without self-consciousness. This biblical style is a creation of the highest literary intuition and tact. No other Western classic has anything like it. It is worlds away from the exquisitely precise, elaborated, gorgeous language of the Homeric poems, the other great texts at the source of Western culture.

The translation of prose, almost as much as of poetry, requires an ear finely attuned to the sound of words. It is fatal when a contemporary Genesis confuses the natural with the vulgar or imitates the cadences of the King James Version. Stiff formality is one extreme, vulgar breeziness the other; in Drydens terms, you must be neither on stilts nor too low. But finding the right tone is not a question of testing the levels of diction the way Goldilocks tested the mattresses, of finding the midpoint between high and low. You cant measure tone with a ruler or a compass. You have to find the sound of the genuine.

It has to be living, to learn the speech of the place.

It has to face the men of the time and to meet

The women of the time.

Over the next few months, as I worked on Genesis and began to talk about it, people kept asking, How is your translation different from other translations? (I felt I was always responding to the question of the youngest son on the first night of Passover.) I tried to explain by quoting Pasternak on tone. If someone persisted and showed real interest, I would sit him down with three other versions of some central passages and let him compare for himself. This is the most direct way.