Mitchell - Parables and Portraits

Here you can read online Mitchell - Parables and Portraits full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014;2009, publisher: HarperCollins e-Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

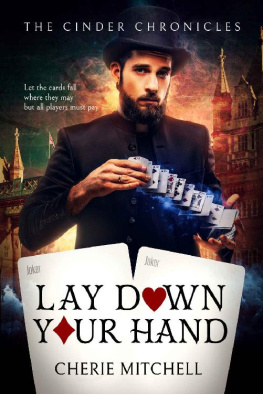

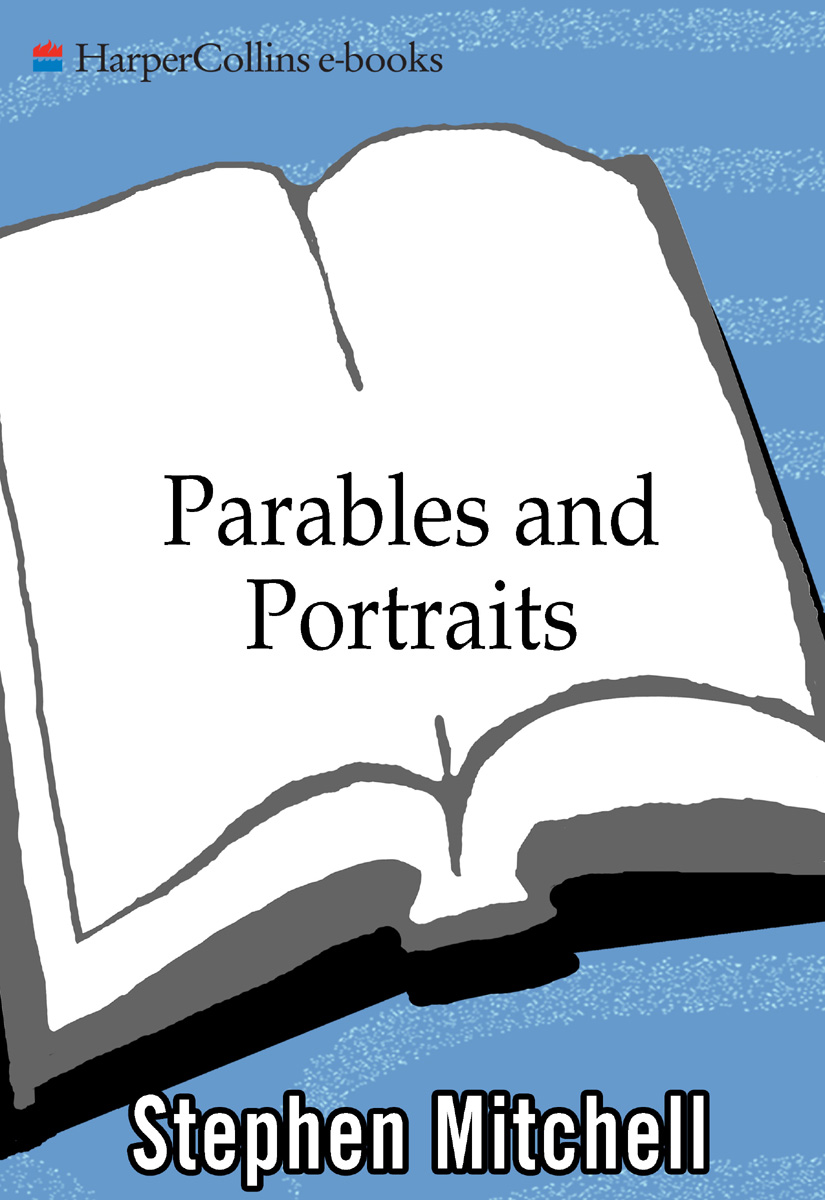

- Book:Parables and Portraits

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins e-Books

- Genre:

- Year:2014;2009

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Parables and Portraits: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Parables and Portraits" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Parables and Portraits — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Parables and Portraits" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Christie McDonald

Cinderella, the soul, sits among the ashes. She is depressed, as usual. Look at her: dressed in rags, face smeared with grime, oily hair, barefoot. How will anyone ever see her for who she is? A sad state of affairs.

Winter afternoons, in a corner of the kitchen, she has long conversations with her fairy godmother, over a cup of tea. The fairy godmother has, accidentally on purpose, misplaced her magic wand. In any case, these transformations are only temporary. The beautiful spangled gown, the crystal slippers, the coach and footmenall would have disappeared at the stroke of midnight. And then what?

It is like the man in the mirror, says the fairy godmother. No one can pull him out but himself.

Ready, set at their respective starting places, staring into the distance between the parallel white lines, they seem like an old married couple about to run through the same argument for the millionth time. Achilles is tense inside his huge golden muscles. The tortoise blinks.

Afterward, they shower; then walk, side by side, to a neighborhood caf.

Its the damnedest thing, says Achilles. The more I catch up, the more reality slows down. Until its no longer even a film. Every time: we finish, immobilized, in a single frame.

With me a micro-meter ahead, the tortoise adds, sighing. He takes another bite of his lettuce sandwich; chews for a while, meditatively; blinks.

Maybe if I tried something different, Achilles says. Maybe a new pair of shoes.

They grow all over Berkeley, along the sidewalks, and start to ripen in May. They are tart but delicious. We stop on our after-dinner walk, reach up and pluck a few. Or fill our pockets from the trees in the empty lot across Vine Street. She bites into the first one as I watch. Mmmm, she says, plum cherries.

No no, sweetheart. Cherry plums.

Oh you. Ive always called them plum cherries. They look like cherries.

But theyre plums. They taste like plums. Theyre called cherry plums because theyre so small.

Well I dont care. I call them plum cherries.

The title of this parable is Plum Cherries.

I needed to write a parable about Hitler. My friend said Dont.

I sat down at my desk and waited. What I glimpsed was an afterworld. There were no physical torments. Only this: that he had to relive his life, as actor and observer both, a thousand times, out to the farthest consequence of his acts, with a constantly growing awareness of the horror, and a constantly growing, unbearable, shame. (In that world there are no ideas to escape into.)

I showed the parable to my friend. He winced. He said, You have no right to imagine it that way.

I said, But according to our sages, on the last day even Lucifer will be forgiven.

He said, You must crawl to the very center of evil before you can see the stars.

Something I left behind

calls me back to your time-zone,

when the son of man spoke Latin,

tucked lace in his collar, and upon

his brachycephalic dome

an equilateral velvet

hat was perched, like a dove.

Through the great marble hallways

of the British Museum, the ghost

of Descartes wandered, bemused.

If I were to find you now,

it could not be in the light.

You would have no chandeliers blazing,

no circle of friends around you

as, steadily, immensely, you poured

the distillates of your Tory

wisdom into their ears.

What, Sir, remains when the body,

one-eyed and scrofulous,

which lurched through the streets as in fetters

and rode horses like a balloon

what remains when that body

casts off its cumbrous frame?

When all the splendid distinctions,

the intricate structures of right

and wrong, the golden yardsticks,

the algebras of dismay

vanish, you are left alone

with the sense of infinite vastness

that a child awakens to, blissful

or terrified, in the dead of night.

Perhaps youre prepared to stay there.

Or perhaps, out of the fond

and unassuaged depths of your spirit,

an image, like a flower blooming

in fast motion, begins to form,

the vision of a shapely leg,

the sweet cavern between two thighs.

And soon it is, yes, a world:

of consonants pullulating

and innocent flute-voiced vowels;

soon there are nests of quartos,

folios flap through the air

like homing geese, and the towers

and bridges of a city loom up

in the gray foreground. Those crowds

are they heading into the Strand?

Those gentlemen in wigs and waistcoats

are they bound for The Cheshire Cheese?

All right, Sir: let us begin

again. You are in the courtyard

of some country alehouse, fidgeting

in a coach of white and gold.

The driver (can you see?) is a dachshund.

The team are four brown mice.

Dont be impatient. Take out

your handkerchief. Blow your nose.

Well be leaving in a moment. London

is no farther off than a sigh.

My wife and my old Zen Master both were born at the cusp of July and August; so I know something about lions. It takes a while to get used to their habits. But once you have let them eat you alive, once they have picked you clean and left nothing but your white bones gleaming in the sunlight, you will find that you are perfectly at ease.

Take this figure of Manjushri, Bodhisattva of wisdom, Buddha before the fact. The lion he is enthroned upon looks like one of those huge good-natured dogs that will let a child pull its whiskers, or almost twist off its ears, without complaining. Chin resting on its paws, tail tucked neatly under its belly, it is imperturbable, because it knows who is the boss.

Manjushri himself sits, formal but relaxed, in a semi-lotus position, with one leg dangling over the lions right flank. Both his hands are clasped around the sword of spiritual discernment (one edge kills, the other gives life). He holds the sword straight up, invitingly, with a little grin.

Living Buddhas are a dime a dozen, the lion thinks, but a good wooden Buddha is hard to find.

Eve bites into the fruit. Suddenly she realizes that she is naked. She begins to cry.

The kindly serpent picks up a handkerchief, gives it to her. Its all right, he says. The first moment is always the hardest.

But I thought knowledge would be so wonderful, Eve says, sniffling.

Knowledge?! laughs the serpent. This fruit is from the Tree of Life .

He had almost reached the end of the tunnel when he heard his friends voice calling him back. The voice was filled with love, but also with sorrow and pity, and not so much fear of death as resistance to it, as if it were an enemy to be expelled or overcome. He had realized so much, during the four days journey, that these resonances struck him as odd, coming as they did from a man of such insight; struck him as laughable, as almost childish. All the dramas of his short, intense life were an instant away from being resolved, dissolved, in the light at the end of the tunnel, which was not a physical lightafter all, he no longer had physical eyesbut a radiant presence, a sense of completion a million times more blissful than what he had felt even in the company of his beloved friend. And the sweet, seductive drama of master and disciple, how childish that had been too, as if a candle flame needed to warm itself before a fire. He thought of his sisters in the old house in Bethany, of Mary anointing their friends feet and wiping them with her hair: the tenderness, the absurdity of that gesture.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Parables and Portraits»

Look at similar books to Parables and Portraits. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Parables and Portraits and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.