John G.T. Anderson | DEEP THINGS |

OUT OF DARKNESS |

A History of Natural History |

University of California Press

BerkeleyLos AngelesLondon

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anderson, John G. T., 1957

Deep things out of darkness: a history of natural history / John G. T. Anderson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-27376-4 (cloth: alk. paper)

eISBN 9780520954458

1. Natural historyhistory. 2. NaturalistsHistory. I. Title.

QH15.A72 2012 2013

508dc232012017404

Manufactured in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (R 2002) ( Permanence of Paper ).

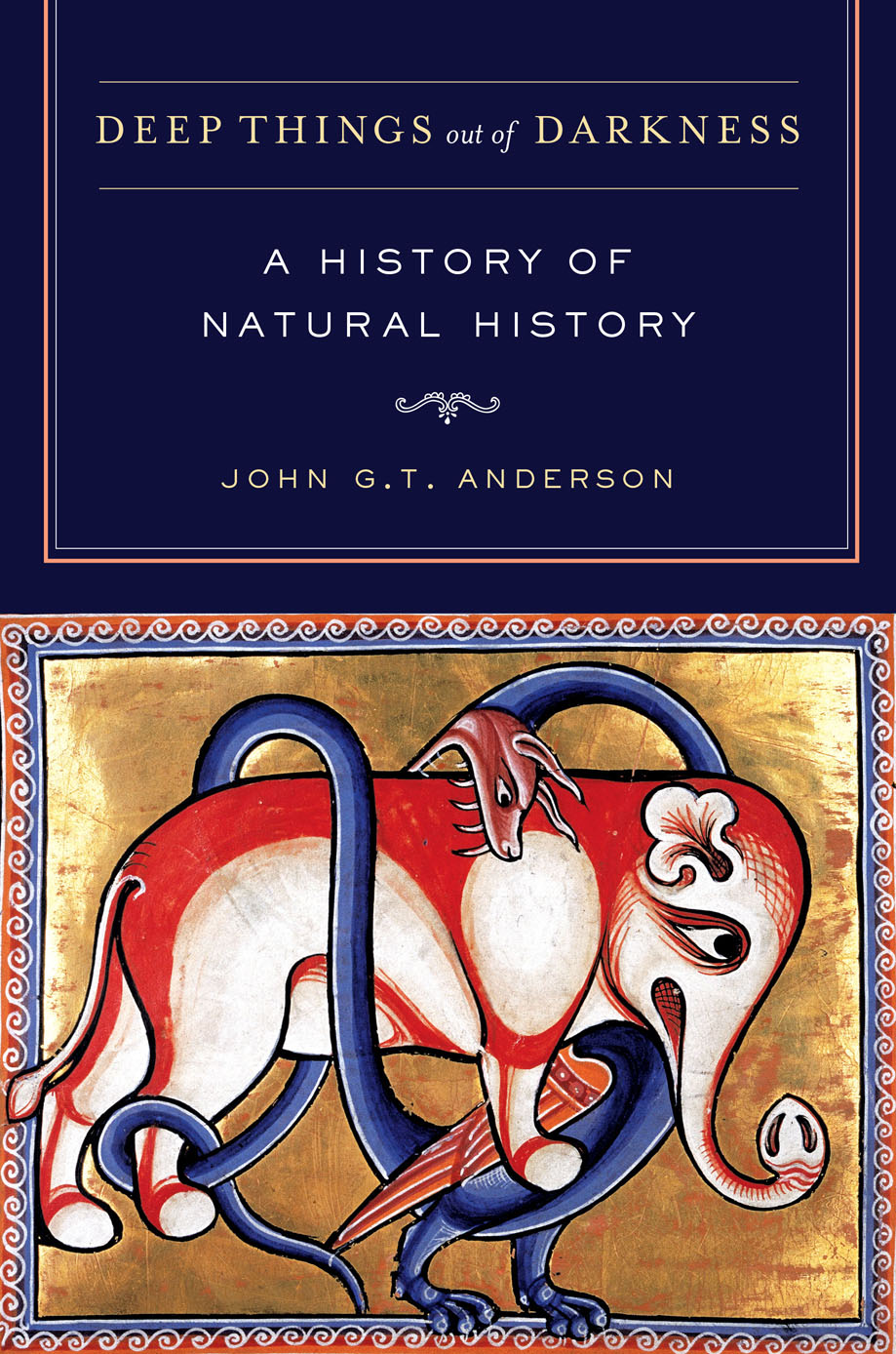

Cover image: Elephant and dragon from the Aberdeen Bestiary.

Cover design: Glynnis Koike.

For Karen, Clare, and David

For things that grow...

He discovereth deep things out of darkness.

JOB 12:22

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FIGURES

MAPS

PREFACE

We are all born natural historians. What happens next is up to chance, environment, and the circumstances of our particular narrative. I was lucky enough to be born of two serious amateur naturalists. My mother had been a lab scientist before children and my father was a classical archaeologist, but both had a deep and abiding passion for wild things, wild places, and careful observation of their surroundings. I grew up in the California of the 1960s and 1970s, when it was still assumed that children could and should spend as much time on their own outdoors as possible. I was a Scout in the last generation for whom camping skills were considered fundamental. Every summer of my teens, I spent up to a month in the Sierra, hiking, camping, swimming in cold lakes, and drinking unfiltered water from snow-fed streams.

After I had had a couple of summers to establish myself at camp, my father made it a habit to visit for a week every summer to be the resident adult and to offer training for the nature merit badge. The badge required us to identify a variety of plants and animals and to gain a good overall sense of where things could be found, what they were likely to be doing, and what else could be expected around them. I remember the fun of sneaking up on marmots sunning themselves on a rocky ledge above camp, and the relief of finding a snowplant in the nick of time to complete my list of plants identified. Nature was regarded as a difficult merit badge, not one to be taken lightly, especially when Professor Anderson was doing the testing.

Later I attended the University of California. I was not a good student. I wish I could blame it on too many afternoons lying on my back watching vultures tip and rock above the golden hillsides of the Bay Area, or too much time on my knees, watching garter snakes slither across dusty trails, but I am afraid that I was just lazy and self-satisfied, and by the time I woke up and realized that my grades weren't going to get me into medical school, it was too late.

For some reason that I still cannot fathom, the pre-med major at Berkeley then required all students to take either Vertebrate Natural History or Invertebrate Natural History. This was a class that had been founded by Joseph Grinnell, the pioneering ornithologist responsible for setting Berkeley on a par with East Coast institutions in field biology. I went to the bookstore and found my first copy of Joel Welty's The Life of Birds. I was lost from the moment I opened the text. The course was team-taught by three remarkable naturalists: Ned Johnson (ornithology), Robert Stebbins (herpetology), and Bill Lidicker (mammalogy). Besides the usual lecture/lab format, the class required half-day weekend field trips to regional parks and wildlife refuges. We were responsible for memorizing a subset of California vertebrates for later examination, and also had to keep field notebooks using the highly formalized Grinnell System (I still remember coming upon two of my erstwhile pre-med friends in the bathroom of the Life Sciences Building busily shaking water on their notes before turning them in. When I asked them what they were up to, they replied that they had rewritten their notesstrictly forbidden under the systemand had then remembered that it had rained heavily on the day of the field trip. The teaching assistants would immediately have cried foul had they received unblemished notes lacking clear evidence of raindrops!).

To my eternal gratitude, Ned Johnson allowed me to both take his ornithology class and to work at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology as an unpaid, extremely junior assistant to the assistant curator. Both experiences put me into direct contact with the lineage of California natural history, extending back to the museum's founders: Joseph Grinnell and Annie Alexander. I remember the museum as a dim, cavernous place entered through an undistinguished door firmly marked No Public Displays. It contained endless stacks of containers of study skins, each carefully labeled, and each label traceable to a field notebook similar to those that I had tried to emulate in class. Sometimes the notes were full of detail about locations and behaviors. Others were less informative about natural history, but contained hints about natural historians. All suggested a remarkable world of adventure and understanding that extended far beyond the endless rows of seats in lecture halls.

Best of all was the Grinnell-Miller Library, a small room at one side of the collections, filled with light and housing the very books that Grinnell had worked with, each bearing his personal bookplate with its motto, Inter folia, Aves: "There are birds between the leaves. Oddly, I cannot remember any single book in the library, but the idea of a library containing books filled with birds caught my attention. The idea stays with me yet.

The next autumn, I managed to slip into Bill Lidicker and Jim Patton's mammalogy course as the only undergraduate, and the die was cast. Besides giving me a lifelong appreciation for taxidermy and fieldwork, Patton made it clear that natural history was, above all, fun. Natural historians got to go to interesting places, see beautiful things, meet unusual people, and ask endless questions. Natural history was science at its living, breathing best. I sat in on the museum lunches, listening to professors and graduate students fight it out over questions of ecology and biogeography, and realized that much of what was being presented to me in lectures as fact was actually at best a set of preliminary hypotheses, and that it would be our job to challenge, check, and refute these facts if we could.

All of this was enormously exciting. I was still not a very good student, but at least I knew what I wanted to do, which was to somehow join the remarkable company of people whose origins stretched back ever farther the more I looked: Ned Johnson was a student of Alden Miller, Miller was a student of Grinnell, Grinnell read Darwin, Darwin read Humboldt.... They went on voyages of discovery, they laughed, they swore, they ate bad food in dreadful conditions, they fought with friends, and they made friends of enemies, and each had a story that became part of a larger story that is history. Over time, I have been lucky enough to do many of the same things, visit some of the same places, and meet some of the people involved in natural history.