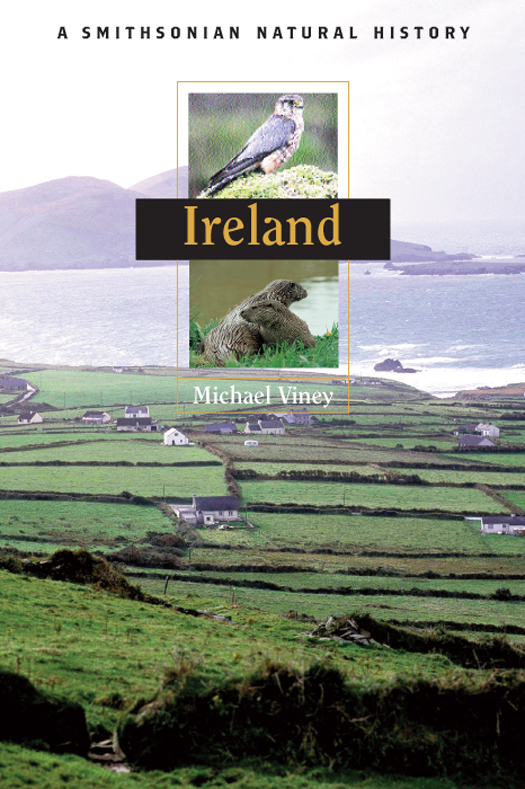

smithsonian natural history series

John C. Kricher, Series Editor

Books in this series explore the diverse plants, animals, people, geology, and ecosystems of the worlds most interesting environments, presented in an accessible style by world-renowned experts.

2003 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Copy editor: Debbie K. Hardin

Production editor: Robert A. Poarch

Designer: Brian Barth

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Viney, Michael, 1933

Ireland : A Smithsonian Natural History/Michael Viney.

p. cm. (Smithsonian natural history series)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 1-58834-057-0 (alk. paper)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-424-3

1. Natural historyIreland. I. Title. II. Series.

QH143.V555 2003

508.415dc21 2002070687

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available

For permission to reproduce the photographs appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. (The author owns the photographs that do not list a source.) Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these photographs or illustrations individually, or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

v3.1

For Ethna and Michele

with love and deep appreciation

Contents

Editors Note

It is often called the Emerald Isle, the land of forty shades of green. An island surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Irish Sea, it is a land of peat bogs, coastal marshes, high cliffs, soft green pastures defined by neat stone walls, and fields ablaze with wildflowers. It is a lush place, where clear skies repeatedly yield to gentle rain. It is Ireland.

This is a region whose countryside rarely provides anything other than the most splendid of vistas. Emerging from between the clouds as the Aer Lingus plane entered final approach to Shannon Airport on my first visit to Ireland in August of 1978, I can still vividly recall the verdant agricultural landscape, a patchwork of rolling pasture populated by sheep and donkeys, bordered by narrow roads and generous hedgerows. Our first stop was the Burren, in County Clare, a region unique for its geology and amazing wildflower display, acres of limestone outcroppings, where trees are absent but where the moist, mild climate permits cattle to forage in the pastures every month of the year. The Cliffs of Moher, near Ennistymon, rise up from the sea, rugged and imposing. High winds greeted me as I walked to the edge of the sheer cliffs to look out on colonies of seabirds, common murres (called guillemots in Ireland), kittiwakes, fulmars, and Atlantic puffins. Gannets were plunging into the sea in pursuit of fish. Soaring on the updrafts were many rooks and jackdaws, members of the Corvidae, or crow family, along with a few choughs (pronounced chuff), also a corvid and one of Irelands rarest bird species. Choughs, recognized by their long, red bill, look otherwise like crows, uniformly black. They appear to take thorough pleasure in soaring to great heights and diving, wings folded back, rolling and turning, as though the bird is imagining its own roller coaster in the sky. This was my introduction to Ireland.

I have had the good fortune to travel widely in Ireland and to experience first-hand some of its diverse natural history. In County Wicklow, south of Dublin, I have walked long distances over soft, boggy peat in search of such species as ring ouzel and dipper. I have marveled at flocks of diverse shore-birds and waterfowl in the marshes at Wexford Slobs, and enjoyed the masses of seabirds that can be found off the coast of Donegal, nestled on the northwestern side of Ireland. I have come to learn something of the extraordinary natural and human history of this fascinating land.

When searching for titles for the Smithsonian Natural History Series it seemed obvious to me that Ireland must be among them. I called my cousin, Bruce Carrick, whose home is in County Westmeath, in the Irish midlands, and asked for his advice about who might author such a volume. Without hesitation, he told me I should contact Michael Viney.

Michael was born in Brighton, England, in 1933, but moved to Ireland in 1961. He had a long career in journalism and television that took a radical turn in 1977 when, along with his wife and small daughter, he abandoned the urban environment of Dublin and moved to rural County Mayo. There he began writing a weekly column for the Irish Times, titled Another Life. The column chronicled Michaels new self-sufficient lifestyle of living off of and in concert with the land, but it soon grew to be the story of his immersion in nature. The column has appeared without interruption for twenty-five years.

Michael has been a member of two scientific expeditions to northeast Greenland (in 1983 and 1987) to study the summer breeding biology of the barnacle goose, a migrant between the Arctic and the west of Ireland. His popular book, A Years Turning (1996), inspired an Irish television series that he and his wife filmed and their now-grown daughter edited. The series documented the Vineys lifestyle and observations of nature over the course of a year.

I am very pleased that Michael Viney has chosen to share his understanding and perspectives on the natural history of Ireland. My cousin was right. You could not ask for a better guide to introduce you to nature in this wonderful land that is Ireland.

John C. Kricher

Preface

My house on a hillside on Mayos rugged west coast looks out to islands, sand dunes, mountains and bogs, and to farmhouses scattered among small, rough fields. Each window seems to hold a different part of Irelands story.

At morning the sun glancing down from the ridge picks out boulders spilled across the hillside by an ice-age glacier. They share the fields with other curious corrugations: broad ridges under the grass, parallel as the wales of corduroy. These areor werepotato ridges, dug before the Famine of the 1840s, when this hillside was dense with people and peat smoke. After the blights catastrophe, the ridges were abandoned in the great emptying-out of rural Ireland by emigration in the late nineteenth century. Today they are grazed by sheep and mountain hares, and as the last, spiky gables of the old thatched cabins melt down into mere rock heaps, the strata of geological and human history lie welded in the landscape.

My study looks out to the Atlantic, where morning rainbows arch above Inishturk, a jagged, Ordovician island with speckles of gold in its veins. Its buckled profile was prefigured 400 million years ago, when the ancient Iapetus Ocean slammed shut (at that time this coast was in Labradors backyard). The rainbows speak for the intense humidity and processional showers that nourish the mosses of Irelands peatlands, the luxuriance of stream-side ferns, the greenness of endless hedged pastures. The oceans influence is mostly benign, yet in geological time the story of weathering and erosion has been a fierce one, carving Irelands initial relief from a huge, uplifted block of sedimentary stone. In todays winters, storms of 80 miles per hour (128 kph) and more batter at the high western cliffs of the islands and send breakers clawing at the sandy fields and dunes below me. As global warming raises the sea level and notches up the power of the wind, images of salt marsh and tundra wake from a suddenly recentmerely postglacialpast.